‘Independent body needed to protect human rights defenders’

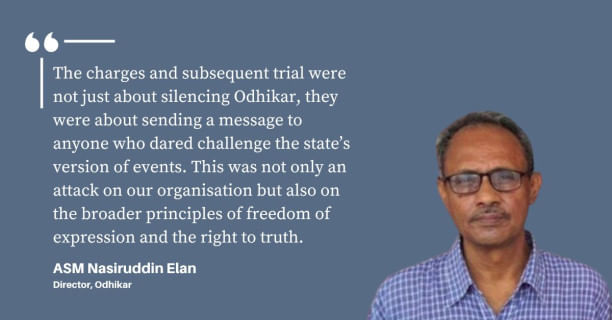

ASM Nasiruddin Elan, director of Odhikar who has suffered prosecution during the ousted Awami League regime, talks about his experience and the overall state of human rights defenders in Bangladesh, in an exclusive interview with Noshin Nawal of The Daily Star.

Could you tell us about your journey with Odhikar and the challenges you have faced during your years of advocacy?

My journey with Odhikar has been filled with challenges, but it has also been one of deep purpose. Odhikar has always stood for factual documentation of human rights abuses, focusing on issues like extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. However, this work came at a significant personal cost.

One of the turning points was the aftermath of the Hefazat-e-Islam rally on May 5-6, 2013. That night, a joint force carried out an operation under the cover of darkness, and widespread reports claimed that many people had died. Given Odhikar's mandate, we felt it was our responsibility to investigate these claims.

We conducted a fact-finding mission and published a report in June that year. The report revealed that 61 percent of the claims were related to extrajudicial killings. At the time, the government categorically denied any casualties. However, later, they contradicted themselves and admitted to an obscure and insignificant number of deaths.

The information minister at the time, Hasanul Haq Inu, via an official letter on his behalf, asked for the names of the deceased. We declined as sharing this information could lead to further victimisation of the victims' families. Instead, we proposed forming a judicial inquiry committee, led by an independent judge. The government ignored this suggestion, and shortly thereafter, charges were filed against us.

What happened after the charges were filed? How did the state respond to your findings?

The charges were filed very quickly. Adilur Rahman Khan, Odhikar's secretary, was the first to be detained on August 10, 2013. He was picked up from his home, and for a time, we had no information about his whereabouts. Later, it became clear that the Detective Branch (DB) of police had taken him.

Not long after, I was named as the second accused in the charge sheet. I surrendered to the court on November 7, 2013, and was sent to jail. We were accused of publishing false information under the ICT Act, 2006. In jail, the environment was hostile, with officials making it a point to mock us. I vividly remember a newly appointed deputy jailer sarcastically asking what the state of human rights in the country is if the human rights defenders are in jail.

How did the judicial process unfold, and what were the key challenges you faced?

The judicial process was incredibly biased. Initially, the case was stayed in the High Court, but after the Covid pandemic, the stay was lifted, and the trial moved forward with undue haste.

The case was eventually transferred to the Cyber Tribunal where it became evident that the government was exerting significant pressure to secure a conviction. The judge handling the case indirectly stated that the report should be removed from Odhikar's website, showing a clear intent to suppress documented evidence rather than address the substance of our findings.

Despite insufficient evidence, both Adilur and I were sentenced to two years in prison and fined Tk 10,000 each. The rushed nature of the trial, combined with the pressure on the judiciary, demonstrated how deeply compromised the system had become.

The Hefazat rally report seems to have been a catalyst for these events. Could you elaborate on its broader implications?

The report was a significant moment for Odhikar. It directly contradicted the state's narrative and highlighted the need for accountability. But instead of addressing the findings, the government attacked us.

The charges and subsequent trial were not just about silencing Odhikar, they were about sending a message to anyone who dared challenge the state's version of events. This was not only an attack on our organisation but also on the broader principles of freedom of expression and the right to truth.

The reality was that our report was factual and based on verified data. The state's response was not about the report's accuracy—it was about silencing Odhikar and discouraging others from documenting human rights abuses.

You mentioned suppression of evidence and pressure on the judiciary. What does this say about the state of institutional integrity at the time?

The judiciary and law enforcement agencies were deeply compromised. The judiciary, instead of upholding the principles of justice, acted under government influence. Law enforcement was weaponised to detain and intimidate human rights defenders. The entire system was used to silence dissent and maintain control. It became clear that institutions meant to protect citizens were instead serving the interests of the regime.

Could you share your experience regarding how you were treated in jail and during the hearings, particularly by the police?

It was extremely humiliating. After the sentencing, even before the formal verdict was fully announced, the courtroom was effectively controlled by law enforcement. They immediately restrained both me and Adilur, physically holding us down and not allowing us to interact with our supporters or even say a proper goodbye. Four police officers grabbed each of us, pushing and dragging us out of the courtroom as if we were violent criminals, which we were not.

Once we reached the prison transfer centre, I remember how I was shoved into the vehicle with such force that I stumbled and fell inside. There was no regard for our dignity or basic human decency. This behaviour was not only degrading but also violated our constitutional rights to dignity and personal liberty, as guaranteed under Article 31 of the constitution.

What rights and methods of protection are currently available to human rights activists in Bangladesh? Do you think they are sufficient?

There is no dedicated institutional mechanism or framework in Bangladesh to protect human rights defenders. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in the past 15 years has only been a pawn, a recommendation-making puppet without any purpose.

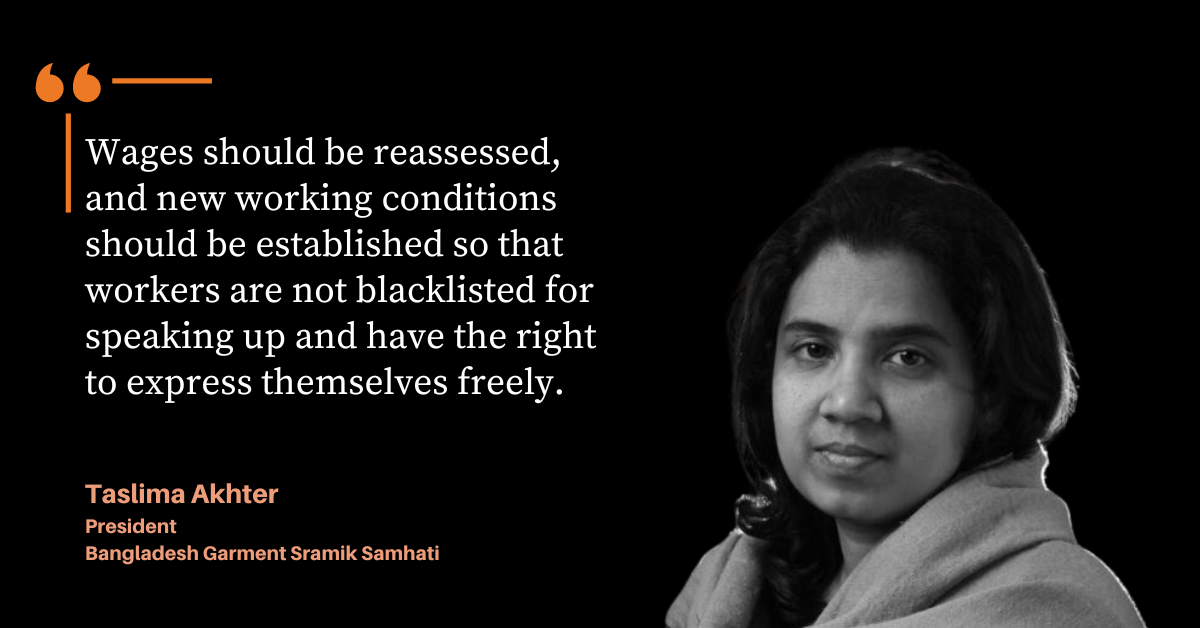

Internationally, the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders provides a set of guidelines and protections, but these are not formally implemented in our country. Activists like us are left vulnerable to harassment, legal persecution, and even physical harm. The state does not ensure adequate safety measures for human rights defenders. On the contrary, it often creates an atmosphere of fear. Activists are frequently targeted with surveillance, arbitrary detentions, fabricated charges, and smear campaigns. The lack of accountability within the law enforcement agencies exacerbates this issue.

In short, the protections that currently exist are far from sufficient. Activists need legal, institutional, and social safeguards to carry out their work without fear of reprisal. Until then, the challenges we face will continue to deter many from standing up for what is right.

Recently, there has been much discussion about violence against minorities, particularly Hindus. How do you view these narratives in the context of your experience as a human rights activist?

The issue of violence against minorities is complex, and much of the narrative surrounding it has been shaped by disinformation. While there were genuine incidents that required attention, many claims were exaggerated or manipulated for political purposes.

For instance, certain actors, both domestic and international, have used these narratives to portray Bangladesh as a country of systematic minority persecution. This disinformation often overshadows the real issues, making it harder to address the root causes and creating unnecessary divisions within society. There are more known incidents of attacks on persons for their political liaisons which are later mispresented in media platforms as minority attacks. The most pervasive issue here is politicisation of communities.

Recently, India has shown significant negativity towards Bangladesh's interim government, largely due to its vested interests and historical affiliation with the ousted Awami League government. The Awami League maintained close ties with India, often aligning with its strategic and political goals. Many Bangladeshis view India's actions as interference, given the widespread sentiment against undue external influence in domestic affairs. India's dissatisfaction stems from losing its reliable ally in the Awami League, prompting attempts to delegitimise the interim government. However, most Bangladeshis do not endorse India's approach, seeking a more balanced and independent foreign policy.

As Bangladesh transitions away from fascist rule, what steps are necessary to rebuild trust and protect human rights?

As per Odhikar's reports, 1,581 people including children were killed, over 18,000 were injured and 550 people sustained injuries that damaged their eyesight during the July uprising. These numbers are expected to be much higher as the tally continues. We as a nation cannot allow a repeat of such instances. Rebuilding trust requires systemic reform. The judiciary and law enforcement must be depoliticised and operate independently. Without this, it will be impossible to ensure justice and accountability.

Disinformation must also be addressed. The state and civil society must work together to promote factual narratives and counter exaggerated claims. This includes fostering communal harmony and addressing any genuine grievances through transparent processes.

Human rights defenders need to be protected. Our work is essential for holding power accountable and ensuring that the voices of the marginalised are heard. Creating a safe environment for this work is crucial for Bangladesh's progress.

What are your reflections on this moment in Bangladesh's history?

If Bangladesh is serious about ensuring human rights, it must establish an independent body to monitor and protect human rights defenders. This body must have the authority to investigate threats, offer legal aid, and ensure that law enforcement agencies do not act as instruments of repression. Without such a mechanism, human rights work and workers in Bangladesh will remain in danger, and the principles of justice and accountability will continue to suffer.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments