Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein and Kazi Nazrul Islam

Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein was born in 1880, Kazi Nazrul Islam in 1899. Apart from their difference in gender, there could not have been more differences in the circumstances of their class and upbringing. Roquiah was born and brought up in an affluent Muslim family of Pairaband. Her brothers went to elite schools in Kolkata. Though she was forbidden to read and write Bangla or English as a child, her brother Ibrahim Saber helped her to learn both languages so that she could write fluently in both. Later, her husband, Sakhawat Hossein, encouraged her to read and write, both Bangla and English.

Kazi Nazrul Islam was born in an impoverished family in the village of Churulia in the district of Bardhaman in West Bengal. Nazrul's father was the khadim or caretaker of a mosque next to his small mud hut. The death of several earlier children led to Nazrul's being given the nickname "Dukhu Miah," the sorrowful one, perhaps also to cast off the evil eye. Initially, Nazrul studied in a maktab, an Islamic elementary school. When Nazrul was about nine, his father passed away, and the young boy was obliged to support his family. This might have meant teaching the children at the maktab, cleaning the mosque, and participating in religious rituals which entailed reciting the Quran.

Sometime in 1915, Nazrul got admitted to Searsole Raj High School, and studied there till 1917. This was the longest time he had spent in one place and in one school. However, he did not sit for the matriculation examination, but went off to join the British Indian Army which had started recruiting Bengalis. Posted to Karachi, Nazrul started subscribing to Kolkata papers and also writing for them.

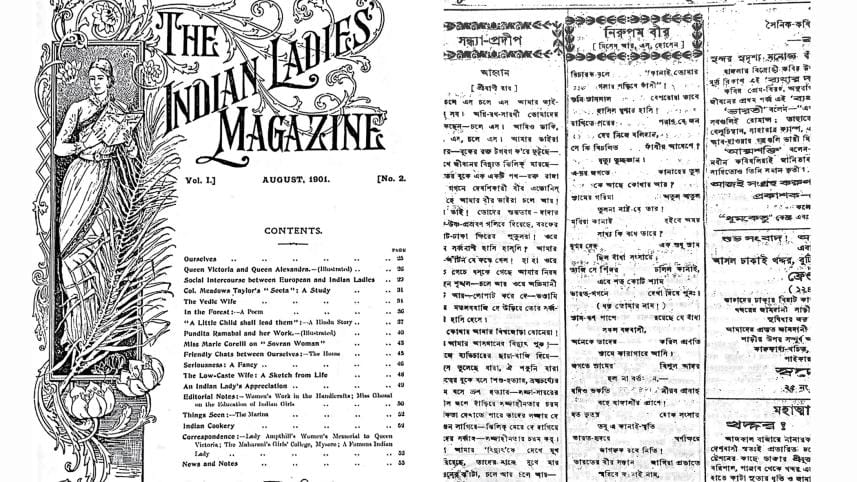

In 1898 – a year before Nazrul was born – Roquiah Khatun was married to Sakhawat Hossein, an Urdu-speaking widower from Bhagalpur. A civil servant under the British Raj, Sakhawat Hossein, not only encouraged his wife to read and write but was so amazed at her piece of English writing that he showed it to Mr. Macpherson, Commissioner, Bhagalpur. Mr. Macpherson commended the quality and content of the writing. We do not know whether Roquiah sent the story herself to Indian Ladies Magazine (Madras) or whether her husband did so. Nevertheless, Roquiah's first published writing appeared in the magazine in 1905. Three years later, her Bangla translation of the story – with some changes – was published as a small book by S. K. Lahiri and Co., Kolkata.

Sakhawat Hossein passed away on May 3, 1909, leaving a large sum to his widow to start a school. Roquiah initially started the school in Bhagalpur but was unable to continue there and moved to Kolkata. It was there that, on March 16, 1911, she re-started Sakhawat Memorial School at 13 Wellesley Lane. Besides persuading Muslim parents to let their daughters enrol in her school and running it, she also had to write letters explaining why certain things were being done or not being done in her school. In addition to these activities, she started writing for local Kolkata newspapers and journals.

Perhaps the earliest Bangla essay of hers that was published was "Pipasha." This piece about Muharram was published in Nabaprabha in Falgun 1308 (Bangla) corresponding to mid-February to mid-March 1912. She also wrote in other journals such as Mahila, Nabanur, Bharat Mahila, Al-Eslam, Bangiya Mussulman Sahitya Patrika, Saogat, Sadhana, Naoroz, Mohammadi, Sahityik, Sabujpatra, Muezzin, Bangalakshmi, Gulistan, and Mah-e-Nau. News about her school was published in The Mussulman under her initials, Mrs. R. S. Hossein.

During his deployment in Karachi, Nazrul subscribed to Bangla journals from Kolkata and also sent them some of his writings. His first publication was a short story "Baundeler Atmakahini" [The Autobiography of a Vagabond], which was published in Saogat in May 1919. The short stories "Hena" and "Byathar Dan" [The Gift of Sorrow] were published in Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Patrika in November 1919 and January 1920 respectively. Roquiah's writings too were being published in Saogat and Bangiya Mussulman Sahitya Patrika. Though it is not known whether Nazrul and Roquiah actually met, it is impossible that they did not know about each other's writings.

A few years ago, I asked Majeda Saber, Roquiah's grandniece who has written considerably on her grandaunt, whether Nazrul and Roquiah had ever met. Majeda Saber did not know. However, even if they did not meet, it is quite evident that Nazrul and Roquiah did meet in print and that they shared some common ideas. Nazrul reveals a deep empathy for women in both his poetry and his fiction. The short story "Rakshushi," about a woman who has killed her husband and gone to jail for her crime, is a sympathetic portrayal of a murderess in her own voice. Nazrul's poem "Nari" demands equality for women.

I sing of equality.

In my eyes, there is no difference

Between a man and a woman.

Whatever is great and blessed in this world,

Has come equally from both, man and woman.

Translated by Selina Hasib

His song, "Jaago Nari Jaago" [Rise Up, Women], gives a clarion call to all women to rise.

Rise up women – rise up like the flaming fire!

Rise up, O wife of the Sun god,

with the mark of blood on your forehead!!

...

Like the fire blazing out of a smouldering heap,

rise up – all you mothers, daughters, wives, sisters!

Translated by Sajed Kamal

In his epistolary novel, Bandhon Hara – which began to be serialized in Moslem Bharat from mid-April 1920 and was published as a book in 1927 – the feelings of the women letter writers reflect Roquiah's ideas.

The narrative of Bandhon Hara seems to focus on the soldier-protagonist Nuru. However, the letters of the women not only contribute to the narrative of the triangular love story but also reflect on the condition of Muslim women in seclusion. For example, Mahbuba writes to Sophie – her friend, who, like her, is also in love with Nuru – about the claustrophobic nature of the inner quarters where women reside. It is a place where even the sun may not enter. But women are not criminals, Mahbuba says. "We are entitled to some freedom, for are we not human beings? Are we not made of flesh and blood, don't we have feelings? Do we not possess a soul?" (Unfettered 50).

After Mahbuba gets married, she writes to Shahoshika, a Brahmo teacher and a family friend, that women are supposed to be self-sacrificing. She tells Shahoshika that she has no wish to be renowned for self-sacrifice. She would like to die but refuses to die locked up in the inner quarters. "If I have to die, I would wish to have all the doors and windows around me open wide . . . . I want to die looking straight at Mother Earth" (Unfettered 149).

In her essay "Subeh Sadek" [Dawn] published in Muezzin (Asharh-Sravan 1337 BS/mid-July-mid-August 1930) Roquiah asked women to proclaim aloud that they were human beings, not possessions. "Buk thukiya bolo ma! Amra poshu noi. Bolo bhogini! Amra asbab noi. Bolo konye! Amra jarau olonkar rupe lohar sinduke aboddha thakibar bostu noi. Sokole somoswore bolo, Amra manush. Mother, proclaim aloud, We are not animals. Proclaim, sister, We are not inanimate objects. Proclaim daughter, We are not ornaments set with precious gems to be locked up in iron trunks. Proclaim together, We are human beings." In Aborodhbashini [The Secluded Ones], published in 1931, several years after Bandhon Hara, she described the claustrophobic, unhealthy, and often fatal conditions of extreme purdah.

These similarities might simply be coincidences. However, it is clear that Nazrul thought highly of Roquiah and that she too reciprocated that feeling. Roquiah had been contributing to several Kolkata journals. In 1922, she contributed two pieces to the newly founded bi-weekly paper, Dhumketu, edited by Nazrul. The paper started publication from 26 Sravan 1329 BS/11 August 1922. A month later, a large extract from Roquiah's essay "Pipasha" [Thirst] was published in the Muharram issue of 16 Bhadra 1329/ September 2, 1922.

Thanks to Selina Bahar Zaman, we have facsimiles of Dhumketu. From this valuable collection we realize that, from the very beginning, the paper not only voiced Nazrul's anti-British views but also displayed his non-communal and non-gendered outlook. Many of the contributors to the paper included Hindu writers as well as women. There were at least ten women who wrote at least once. One of these included a ten- or eleven-year-old girl as well as a thirteen-year-old girl, the former Hindu, the latter Muslim. Mrs. M. Rahman, to whom Nazrul dedicated his book Bisher Banshi, wrote several times. Roquiah – as Mrs R. S. Hossein – was published twice in Dhumketu.

We do not know whether Roquiah sent the extract from "Pipasha" herself or whether Nazrul asked her for the piece for the special issue of twenty pages. The extract published in Dhumketu reflects on the plight of Hazrat Imam Hossain and the group of warriors, women and children, who accompanied him on his tragic journey to Karbala.

The only other piece by Roquiah to appear in Dhumketu was a poem, "Nirupam Bir" [The Dauntless Warrior], published on 5 Ashwin 1329 BS / September 22, 1922. Unlike "Pipasha," the poem does not seem to have been published before. This time, Roquiah might herself have sent the poem to Dhumketu. She would not have had to go in person to the office of Dhumketu. With a good postal service, contributions were mailed to journals.

"Nirupam Bir" is a remarkable poem from a woman who has been called an "Islamic Feminist." The 1 Bhadra 1329/ 18 August issue of Dhumketu had published a photograph of Kanailal Dutt (1888-1908). Did this inspire Roquiah to write the poem? Kanailal was a revolutionary belonging to the Jugantor Group. Arrested with a number of other revolutionaries, he was imprisoned in Alipore Jail. There, along with another revolutionary, he succeeded in assassinating Narendranth Goswami, a government approver. Kanailal was hanged on 31 August 1908. He was the second revolutionary to be hanged by the British after Khudiram Bose – whose picture also appeared in Dhumketu.

In the poem, Roquiah eulogises Kanai as the dauntless warrior. The poem begins with the magistrate telling Kanai that he will be hanged. But Kanai – addressed here as Shyam, another name of Krishna – laughs. The one who willingly sacrifices his life does not fear hanging. "Moriya kanai hobe omor/ Shadhyo ki bodhe tarey? By dying Kanai will become immortal. Who can slay him?" The poem ends with a strident call hailing Kanailal: "Bolo bolo 'Bande Shyam.'" It is a brave poem by a woman who was the widow of a government servant, a woman who ran a school for Muslim girls and promised their parents that purdah would be observed.

There were no Muslim revolutionaries at the time – though Nazrul's friend Muzaffar Ahmad was a communist – and in Mrityukshudha Nazrul would describe a Muslim Bolshevik and in Kuhelika he would portray a Muslim revolutionary. In his two poems on Durga, "Agamoni" and "Anandamoyeer Agamane," published in the Puja issue of Dhumketu on 9 Ashwin 1329 BS /September 26, 1922, Nazrul used the legend of the goddess to call for the overthrow of the British. In his editorial in the thirteenth issue of Dhumketu, 26 Ashwin 1329 BS / October 13,1922, Nazrul called for complete independence from the British: "'Dhumketu' bharater purno swadhinata chay." He quoted a line from his poem "Bidrohi": "Ami aponare chhara kori na kahare kurnish" [I bow to no one but myself]. Unlike Khudiram and Kanai, Nazrul did not resort to bombs or pistols, but to soul-stirring words. Just as in some of his writings, Nazrul revealed the feminist perspectives of Roquiah, in this poem Roquiah approached the revolutionary spirit of Nazrul.

Selected Bibliography

Hossein, Roquiah Sakhawat, "Subeh Sadek." Rokeya Rachanabali ed. Abdul Mannan Syed et al, revised edition. Bangla Academy: 1999.

Islam, Kazi Nazrul. Unfettered (translation of Bandhon Hara).Translated by The Reading Circle Nymphea Publication: 2015.

Zaman, Selina Bahar, ed. Nazruler Dhumketu Nazrul Institute: 2013.

Niaz Zaman, Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh, is a writer and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments