The untold story of Franklin Book Dhaka: In the shadow of the cold war

The Cold War was a war of armaments and ideologies—but it was also a war of words, fought in classrooms, libraries, and on the printed page. As part of its strategy to win hearts and minds in the newly decolonised world, the United States launched the Franklin Book Program (FBP) in 1952, deploying books as emissaries of liberal democracy, scientific progress, and capitalist modernity. In East Pakistan, where questions of language, identity, and cultural autonomy shaped the politics of everyday life, Franklin's arrival intersected with a growing Bengali intellectual movement. At the centre of this intersection stood A.T.M. Abdul Mateen, the founding director of Franklin Dhaka, whose vision and leadership transformed the programme from an American soft-power project into a vehicle for the cultural and linguistic assertion of East Pakistan's Bengali intelligentsia.

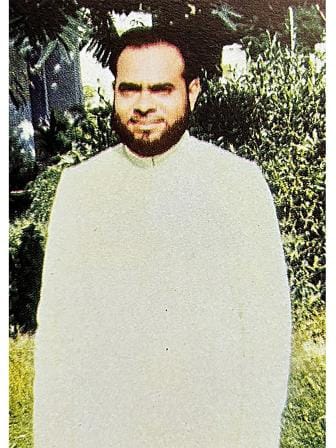

Mateen's path to this position was shaped by the intellectual trajectories of the Indian Muslim middle classes in the twentieth century. Educated at Aligarh Muslim University and later at Cornell University, where he completed a master's in international economics, Mateen returned to Dhaka as a lecturer in economics and history at Ahsanullah Engineering College. With no prior experience in publishing, he was inducted into Franklin's fold in 1955 by Datus C. Smith, Franklin's founding president, who had been persuaded by Pakistani diplomat and literary figure Ahmad Shah Bokhari to extend the Franklin model from Lahore to Dhaka. It was a moment of convergence—between American cultural diplomacy and East Pakistan's search for a modern intellectual identity.

From a modest office at 29, Purana Paltan, Ramna, Mateen led a skeletal team tasked with producing high-quality Bangla translations of American and global works in science, literature, and the social sciences. What emerged under his stewardship was more than a publishing programme—it was a print revolution, grounded in Cold War geopolitics but animated by local aspirations for linguistic dignity and intellectual autonomy.

Franklin's First Publication and the Quest for Local Legitimacy

Franklin Dhaka's first publication was not a translation of an American classic but an original biography of Benjamin Franklin, written in Bangla by Syed Abdul Mannan and released on August 14, 1956, to mark Pakistan's Independence Day. The book's symbolic timing and content—a life of a man who had helped unify the American colonies—was a deliberate choice. In his preface, Mannan expressed hope that Franklin's example would inspire Pakistan's youth to work towards national reconstruction. A new circular introducing the book, authored by Mateen himself, described Franklin's mission as part of a "sacred duty to impart knowledge to the people deprived of such opportunities."

This rhetorical positioning was crucial. Franklin's success in East Pakistan hinged not only on its ability to produce quality books but on the legitimacy of its operations in the eyes of local intellectuals, writers, and policymakers. Mateen knew that to avoid the suspicion that Franklin was a mere cultural outpost of the United States Information Service (USIS), the programme needed to project itself as a partner in national development. And so, Franklin Dhaka consciously fashioned its identity as an indigenous initiative—staffed by local translators, artists, editors, and publishers—working to address a chronic shortage of Bangla-language reading materials in the fields of science, economics, technology, and the humanities.

Franklin Dhaka's Challenge to Commercial Publishing Norms

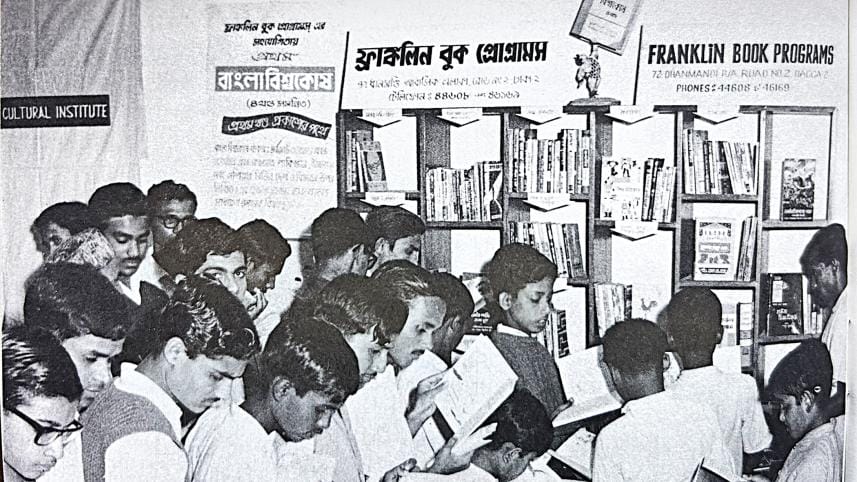

Over the next few years, Franklin Dhaka established partnerships with leading local publishers such as Majid Publishing House, Mullick Brothers, Wadud Publications, and Purbachal Prakshano. A distinctive collaborative model was developed: translators, editors, proofreaders, artists, and calligraphers were all compensated, and the final products were designed to match international publishing standards. The aim was not only to disseminate knowledge but also to set a new benchmark for book production in the country. Franklin books became instantly recognisable for their attractive design, rigorous editing, and thematic relevance.

This was no small feat in a publishing ecosystem dominated by textbook monopolies. Many established publishers were reluctant to cooperate with Franklin, viewing it as a foreign competitor. Mateen lamented what he saw as the narrow commercialism of these publishers, whose primary interest was the mass production of low-quality textbooks and exam guides. "A nation's character is built not by textbooks," he wrote to Franklin's headquarters in New York, "but by books other than that."

To counter this publishing inertia, Mateen actively nurtured new entrants—individuals with education, integrity, and nationalist zeal. He described his cohort of publishers as "graduates and outstanding leaders in their respective fields," confident that "the history of Cairo, Lahore, and Tehran may also be repeated here at Decca." Franklin's cultural politics was thus intricately tied to an emerging Bengali middle class eager to claim its space in the postcolonial public sphere.

Franklin Dhaka and the Scientific Lexicon of Bangla

At the heart of this effort lay a linguistic project. If Bangla was to replace English as the language of education and governance in East Pakistan, it required a corpus of modern literature. The political rhetoric surrounding linguistic rights often ignored the practical task of developing Bangla's scientific and administrative vocabulary. Franklin, in this context, became a tool for language development. Its Bangla translations of American books in physics, chemistry, biology, home economics, and political science filled an urgent pedagogical void.

The Basic Science Series, for instance, employed the expertise of respected scientists such as Prof. Fazlur Rahman, Prof. Zahurul Huq, and Prof. Abdullah Al-Muti. These were not simply translations—they were acts of cultural adaptation, rendering modern science intelligible and accessible in Bangla. For vocational institutes like the Dhaka Polytechnic, Franklin books became indispensable, particularly for students who lacked English proficiency. As one instructor, Sultanuddin Ahmed, wrote, "the severe shortage of technical books and writings available in Bengali" was hampering national progress.

Cultural Censorship and Strategic Adaptation

Franklin Dhaka also had to navigate the delicate religious and political terrain of East Pakistan. When considering the translation of H.A.R. Gibb's Mohammedanism, a respected but Eurocentric history of Islam, Datus Smith advised that the book be reviewed by "not too liberal students of Islamic doctrine" before translation. A similar caution was applied to Cressy Morrison's Man Does Not Stand Alone, which used science to argue for the existence of God. Mateen ensured that two learned theologians reviewed the manuscript to ensure its alignment with Islamic values.

These accommodations reflected the dual imperatives of Franklin: to disseminate American ideas while respecting local cultural and religious norms. Franklin's publishing decisions were guided by the understanding that cultural diplomacy required restraint. Illustrations were redesigned, content revised, and even titles changed to avoid offence and gain legitimacy.

Books and the Burden of Foreign Aid

From its inception, Franklin Dhaka faced a peculiar dilemma. It offered high-quality books and professional compensation for authors and artists at a time when local publishers were primarily focused on the profitable textbook market. Yet, it also carried the stigma of being a foreign initiative, vulnerable to accusations of cultural imperialism. These tensions were evident in public discourse. A review published in the Bangla literary magazine Meghna in July 1956 described Franklin as a "necessary evil" of foreign aid. Discussing Chhoto Theka Baro—a Bangla translation of Sarah K. Bolton's Lives of Poor Boys Who Became Famous, rendered by journalist Serajuddin Hussain—the reviewer warned that "our culture [might] be held to the apron strings of American politics."

Yet the same review conceded Franklin's importance, especially in a literary market where publishers dismissed poetry and fiction as "nonsensical affairs" and were "overwhelmed with the dream of becoming rich overnight." Franklin, it noted, "saved, at least some of our literateurs and artists… from the pangs of hunger." That the translated book added new characters and was praised for its narration, emotion, and cover design by A. Sabur underscores Franklin's success in fostering a literary aesthetic that resonated locally—even while remaining entangled in geopolitical anxieties.

Translation as Transformation

Mateen's advocacy of translation was deeply rooted in a modernist ethos. He drew parallels between Franklin's work and the great translation movements of Islamic history—under the Abbasids, and in medieval Bengal under Muslim rulers. At public events, he cited the Hadith: "Knowledge is the gem which the Muslims have lost." He argued that translation was the only means through which the masses could access global intellectual developments. "Facts about science are universal," he reminded his audiences, "and these books, although translations, have yet retained the maximum amount of originality." He compared Franklin's work to the translation movement of the Abbasid Caliphate: "It is no exaggeration to say that after the days of Haroun-al-Rashid and Mamun, Franklin Publications… is the largest single well-planned international translation program undertaken by any country or cultural organization on such a gigantic scale."

Franklin Dhaka consciously resisted the notion that translation was a mechanical act of linguistic equivalence. Translation became an interpretive and creative enterprise—one that transformed original texts into new works of literature in their own right. This view clashed with the prevailing nationalist emphasis on original writing as the sole site of literary merit and authorship.

Mateen's team, which included translators such as Ashraf Siddiqui, Serajuddin Hussain, and Principal Ebrahim Khan, produced works that were both faithful and transformative. They coined new terms, adapted stylistic conventions, and sometimes restructured content to better suit local sensibilities. In many cases, only selected chapters were translated, titles were changed, and illustrations replaced. The result was a genre of books that were foreign in origin but Bengali in form—books that looked and felt local.

Still, this process provoked debate. The issue of linguistic purity versus evolution became a flashpoint in the reception of Franklin's books. In a review of Chhoto Theka Baro, Shamsul Huq of the British Information Services praised the literary quality of the Bangla translation but criticised the use of Urdu and English loanwords, arguing they undermined the integrity of the Bengali language. His critique echoed broader anxieties among Bengali intellectuals over the creeping influence of Urdu in East Pakistan's cultural landscape.

Against Linguistic Purism

Principal Ebrahim Khan, a prolific Franklin translator and educator, dismissed such purism as "madness." He argued, alongside linguist Dr Muhammad Shahidullah, that Bangla had always been a hybrid language, shaped by centuries of Persian, Arabic, Portuguese, and English influence. "We should not be ashamed that Bangla is a mixed language," Shahidullah declared at a 1948 literary conference. In this view, translation and linguistic borrowing were not threats to identity but instruments of intellectual growth.

This debate unfolded within a broader context of postcolonial language politics. For Franklin's translators and editors, the goal was not simply to replace English with Bangla, but to make Bangla capable of bearing the weight of modern knowledge. This required technical innovation, cultural negotiation, and institutional support. Franklin books were not just literary exercises; they were infrastructural interventions in the nation-building project.

Fidelity or Fluency?

The politics of translation extended beyond vocabulary to the structure and rhythm of the text. A reviewer in Pakistan Observer criticised one Franklin translation for adhering too closely to the English original, resulting in awkward and grammatically flawed Bangla. "Every word in each sentence has been faithfully rendered," the reviewer noted, "though in doing so they have often offended rules of grammar and composition."

In contrast, Dr Sajjad Hussain of Dhaka University praised the "dynamic" prose of the Bangla version of Steinbeck's The Moon is Down, translated by Mahiuddin Ahmed, but criticised the translator's literalism and questioned the title's rendering as Astorag—a word that in Bangla evoked "sunset" rather than the novel's darker implications. This debate revealed the tightrope walked by Franklin's translators: between fidelity to the original and resonance with local meaning.

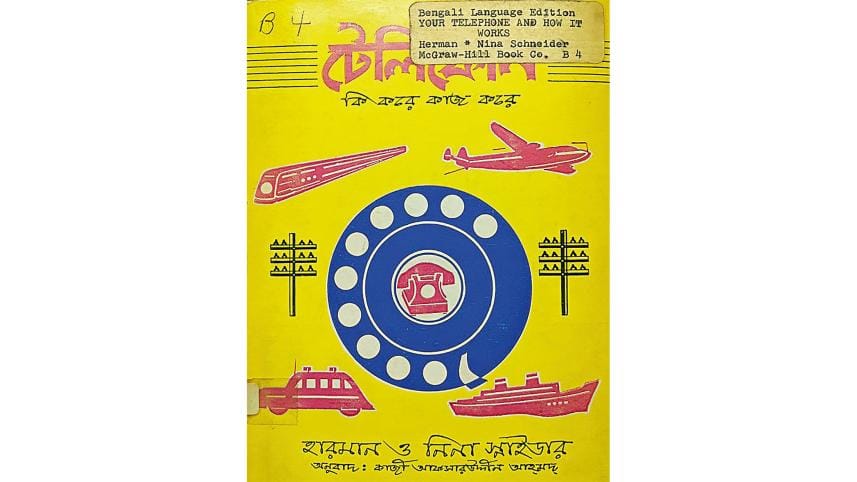

And yet, there were successes that silenced the sceptics. One review of The Telephone Book, translated by Qazi Afsaruddin Ahmed, celebrated the translator's ability to render a foreign text in such natural Bangla that it read like an original work. "While reading the book, I was charmed by the translator's ability to produce something foreign in his own language in a way so that it appears… as if he was reading something original."

Reclaiming Intellectual Autonomy

The Bangla editions of Franklin books were thus not just translated copies of American originals. They were new books, reshaped by cultural context, political prudence, and literary craft. This transformation was recognised by readers, who increasingly viewed these works as local contributions. Translators emerged as literary figures in their own right, and Franklin's authorship became a shared space—between the American original, the Bengali translator, and the reading public.

Franklin's emphasis on adaptation over literalism ultimately enabled its greater acceptance. Major projects like the translation of Edward R. Murrow's This I Believe included new contributions from Pakistani voices, allowing the book to speak more directly to its audience. In doing so, Franklin Dhaka mirrored the ambitions of its director: to create a Bengali literary public grounded in the universal values of knowledge and shaped by the specific conditions of postcolonial society.

Demanding Reciprocity in the Franklin Programme

During the 1957 visit of Franklin's New York-based directors, Mateen organised a series of receptions, field visits, and roundtable discussions with Bengali intellectuals. The Bengali press, including Daily Azad and Ittefaq, covered these events in detail, noting the programme's contributions and highlighting the demand for publishing original works by Bengali authors—not just translations. Indeed, the call for a "reverse flow" of literature became increasingly vocal. Principal Ebrahim Khan and Prof. Ashraf Siddiqui, among others, urged Franklin to publish Pakistani writings for international audiences. Their concerns reflected a broader anxiety: that without such reciprocity, Franklin would be reduced to another conduit for American cultural imperialism. To their credit, Franklin's leadership responded by proposing Franklin Fellowships for Bengali authors and acknowledging the need for more locally authored content.

The Legacy of A.T.M. Abdul Mateen

Under A.T.M. Abdul Mateen's leadership, Franklin Dhaka published over 100 titles and printed nearly half a million copies in less than five years. The range of publications—spanning juvenile literature, technical manuals, science textbooks, biographies, novels, and philosophical treatises—addressed a critical shortage of educational and general reading materials in Bangla. These books circulated widely across schools, universities, and homes, transforming Franklin into more than a conduit of American cultural diplomacy. It became a catalyst for redefining Bangla as a language capable of bearing the weight of modern knowledge and intellectual inquiry.

Mateen would go on to enter national politics, eventually becoming the Deputy Speaker of Pakistan's National Assembly on the Awami League ticket in 1966. Yet, his most enduring legacy lies in shaping the modern identity of the Bangla language—not through protest or polemic, but through print. Through tireless correspondence, coalition-building, and cultural diplomacy, he reimagined Bangla as a language central to the assertion of national cultural identity. His vision echoed that of his mentor, Datus C. Smith, who described books as "the invisible capital of the nation." Mateen laid the groundwork for a modern Bengali literary public sphere, anchored in a vibrant and forward-looking publishing industry. This contribution was no mere footnote to Cold War history; it was a foundational chapter in the intellectual development of Bangladesh.

In today's Bangladesh—where debates over language, identity, and education remain deeply resonant—Mateen's pioneering work with Franklin stands as a reminder of how books, and those who believe in their transformative power, can quietly shape nations. The story of Franklin Dhaka under Mateen's stewardship is not simply that of an efficient administrator or cultural intermediary; it is the story of a generation of Bengali intellectuals who, in the shadow of West Pakistani hegemony and amidst the turbulence of Cold War politics, imagined nation-building through books.

Nadeem Omar Tarar is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin, TX, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments