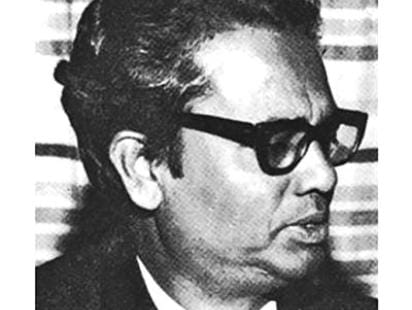

The life, work and death of a political intellectual

Munier Chowdhury, known primarily as the author of iconic plays such as Kabar and Roktakto Prantor, was also a noted educationist, linguist, literary critic and a staunch Bengali nationalist. As an individual engaged in leftist politics of the time, he was arrested in 1952 for protesting against police repression and the killing of students during the Language Movement. On December 14, 1971, he was picked up along with a large number of Bengali intellectuals by Pakistani collaborators, never to be seen again. Remembering the life and death of this Bengali intellectual who did not shy away from politics, this issue of In Focus brings two articles written by Shamser Chowdhury, his younger brother, who passed away in 2012. The articles reflect on the life and works of the man and reminisces the day when he was picked up.

A voice of protest

Shaheed Munier Choudhury and Bangladesh are inseparable. He was kidnapped by the infamous collaborators of the Pakistani occupation forces known as Razakars (Al-Badr), less than 48 hours before our independence. No one really knows what happened to him, but he is believed to have been brutally killed along with scores of intellectuals kidnapped and murdered at about the same time. A brilliant life was cut short at 46 only. Years after independence the legacy of Munier Choudhury continues to live.

Munier Choudhury was a brilliant scholar, a champion of Bangla and Bangalee nationalism. He was the founding father of modern Bangla drama in Bangladesh. Throughout his life he fought against all forms of narrow thinking and religious extremism.

Munier Choudhury's quest for knowledge was not only insatiable but it came to him most naturally. He once told his elder brother National Professor Kabir Choudhury: " I do not study to get a first class, but I see no reason as to why I should not get a first class if I study hard."

Munier Choudhury's academic pursuits were both intense and diversified. He did his Master's in English in 1947. Later he appeared for both MA part one and two of Bangla while still in jail as a prisoner and obtained first class first in both examinations, a feat that few could achieve in the country before or after him. He also wrote his famous play Kabar, immortalising the 1952 Language Movement, while he was still in jail in 1954. Munier Choudhury had a passion for the study of languages. He went to Harvard University in USA, where he obtained his Master's in Linguistics in 1958.

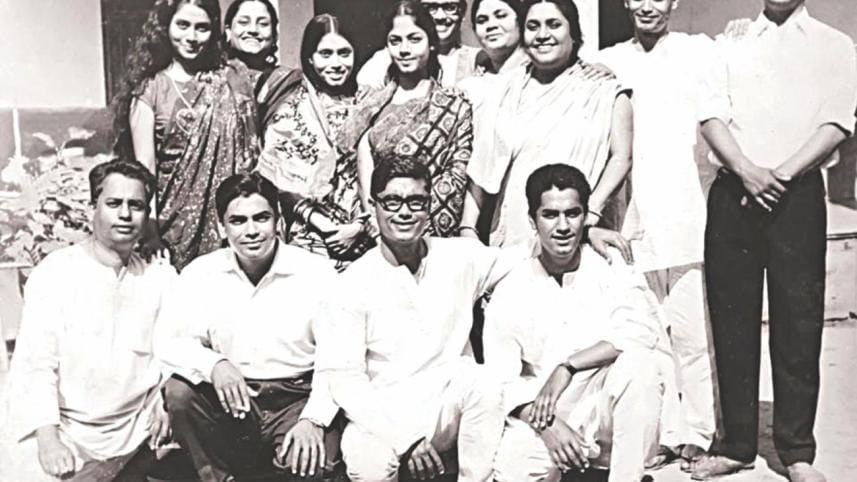

He has often described by his colleagues and students alike, as a wizard of a teacher. He was a unique and an eloquent speaker both within the confines of his classroom and outside. Often students from departments other than his Bangla Department thronged to his classroom and listened to his deliberations, spellbound. To his colleagues, he was more of Munier Bhai than Munier Sir. To this day many of his students, who are well placed within the country and overseas, remember Shaheed Munier Choudhury with extreme reverence.

Munier Choudhury was a die-hard nationalist and indeed a champion of Bengali nationalism. His participation in the Language Movement and subsequent confinement in jail for long two years (1952-1954) bear testimony to the fact. He relentlessly worked towards development of Bangla through various research works. One of his unique contributions towards the development of the language was redesigning and modernising the keyboard of the Bangla typewriter in collaboration with the Remington company of the then East Germany sometime during the mid-60s. As a result, a considerable improvement was made over the keyboard of the typewriters of the company. Although over the years further developments have taken place since then; Munier Choudhury was the pioneer in this regard. To this day Remington typewriters with Bangla keyboards carry his name "Munier Optima".

Munier Choudhury was unquestionably the father of modern day Bangla drama in Bangladesh. Kabar was included as a textbook of the curricula of the Bachelor of Arts. He wrote a number of other plays like Raktakta Prantar (1962). Drama and Munier Choudhury lived side by side. He was an accomplished stage actor too and acted in his own play Roktakto Prantar sometime in 1962. One of his short plays Ektala-Dotala has the rare distinction of being the first ever Bangla drama telecast on TV as early as 1965.

Munier Choudhury during the short span of his professional career and academic pursuits received many prestigious awards and laurels. It is indeed sad that the life of such an extraordinary man was cut short.

Munier Choudhury was a visionary who symbolised the very voice of protest against all kinds of social injustices and exploitations particularly in the name of religion. He was relentless in his crusade against the extremist mullahs and the extremists in general who ultimately masterminded his kidnapping and killing in 1971.

Today the country is passing through one of the most difficult periods of its existence. We needed a Munier Choudhury to be amongst us at this critical hour more than ever before. Evil forces are once again up and about conspiring to carry on with their heinous acts threatening the very foundations of our independence.

The article was first published on December 14, 2006.

The day they took my brother

This December 14, 2003 was the 32nd Anniversary of my illustrious brother's kidnapping. My brother and I were watching from the outer balcony of our ancestral home in Central Road, the Indian fighter jets flying right over our heads, apparently hurling rockets at a house where presumably the then Commander of the Pak Armed Forces General Niazi had taken refuge. It was 11:45 am. The shelling and rocketing which began around 7 am had come to a sudden halt.

My mother called out from the inner yard of the house opposite the outer verandah on the ground floor, "Now that there is some respite from the air raids, the two of you should have a quick shower and have lunch. I am laying the table". At this we both came down and my brother went for his bath at the makeshift bathing place which was located at the inner yard of the house having a bucket, a plastic mug and a water tank capable of storing about ten to twelve buckets of water on a six by three feet of concrete platform.

At about this time as I was waiting for my brother to finish his bath and make way for me I saw that a microbus camouflaged in mud had stopped right in front of our main outer entrance and about three or four young men alighted from the bus, all in militia uniform. All had rifles in their possession. The two of them were making rattling sounds beating on the lock hanging from the large gate made of wrought iron apparently trying to attract attention of the inmates of the house. I was watching all this from the window of one of the rooms on the ground floor, which provided a clear view of the gate and the front yard including the street right across.

My first reaction was to ignore, wait and watch and at the same time hoping that they would give up and disappear. No such thing happened. They seemed determined and now even began to shout. Seeing this I finally came out and decided to face these people who appeared from nowhere. Besides I was quite apprehensive of their purpose since the entire city was under curfew imposed by the Pak Army. As I approached the gate one of the three people now standing on the outer side of the closed gate asked me to open the gate to which I responded by saying that I would like to know the purpose of their visit. The three of them said in one voice that they had came to see Munier Sir. I was now getting somewhat nervous and told them that they could not see him since he was unwell. At this, one of them looked at me angrily and asked me to open the gate in a terse voice. I felt I could no longer resist them from coming into the yard. After some exchange of words leading to arguments and counter-arguments about my brother being sick and his inability to meet them, I finally asked these people (who I later learned were Razakars) to wait till I inform my brother.

As I went in, I found my brother standing in front of the glass window located on the middle section of the stairs, still in a vest and a lungi. Before I could say something, he wanted to know if these people had come to see him. Having had confirmation from me he asked me to tell them to wait. A little while after he returned wearing a punjabi and the lungi and in a pair of slippers. As he approached the Razakars , they greeted him and said that they had come to take him to the police station for some questioning.

At this my brother wanted to see their authority by way of a Warrant of Arrest. After considerable exchange of words the Razakars could neither persuade my brother to accompany them nor could they produce any document in support of his arrest. As matters came to a pass my brother refused to accompany the Razakars. As I was watching the proceedings standing beside him, one of the Razakars suddenly rushed behind my brother and held the gun to his back ordering him to move. I was completely dumbfounded at the sudden turn of events and followed my brother to the entrance door of the bus. And now as he was entering the bus he turned to me and said " Rushdi (a name by which my family used to address me) I better go."

***

Thirty two years have gone by since that frightful incident, I have neither seen nor heard from him. To this day I keep asking myself: "Is he dead, if so who killed him and why? Was he tortured to death? Who was he thinking of before the end came? Was he thinking of his mother whom he left waiting at the dining table to join her? Or was he thinking of his wife and children whom he had left behind?" My mother has left this world (June 2000). I am glad that at least her long and painful wait for her son was over. As for me, the gaping wound caused since my brother disappeared still remains, yet I feel no real pain. I have learnt to live and cope with the tragedy. But what I find even harder to deal with is the current state of our beloved homeland. The tragic state of our country has long overshadowed my personal loss.

The article was first published on The Daily Star, December 15, 2003.

Comments