The enduring impact of Abul Mansur Ahmad’s journalism

The year 2023 marked the centennial of Abul Mansur Ahmad's journalism—a milestone that holds not only significance but also relevance in understanding his enduring impact. As a professional journalist and editor, his work ethic and creativity were nearly unparalleled from the outset. In the third decade of the twentieth century, if we examine his journalistic path from both national and international perspectives, today's journalists can gain insights into a unique guideline. His unwavering dedication, diligence, and passion have propelled journalism and the newspaper industry to both practical and theoretical heights. From his career in journalism, individuals can glean invaluable elements, whether they are newspaper owners, journalist-editors, professors, researchers, writers, philosophers, or rational thinkers.

Abul Mansur Ahmad embarked on active journalism in 1923, immersing himself in the field with dedication fueled by personal endeavors and the collaborative spirit of his friend, Abul Kalam Shamsuddin. He authored two notable articles: first, "Sahi Boro Taiyabnama," a satirical piece on politics, and second, "Sabhyatar Dwaitoshashon," an extensive philosophical-political essay. The latter, specifically, drew the interest of Muslim journalists.

Abul Mansur Ahmad began his journalism career at the newspaper "Soltan," initially serving as a sub-editor with a monthly salary of Tk30. Initially satisfied with his work, he managed to negotiate an increase to Tk40 within a short period. During his time at Soltan, he formed a close acquaintance and friendship with Maulana Muhammad Akram Khan, who personally requested Abul Mansur Ahmad from Maulana Moniruzzaman Islamabadi due to his captivating writing and clarity of expression. After one and a half years at Soltan, he concluded this phase of his career and joined "Mohammadi," where he continued as a sub-editor, receiving a salary of Tk50.

At Mohammadi, he worked alongside colleagues like Fazlul Haque Selsbarshi and Muhammad Wajed Ali. The staff included three members, two of whom were seniors. It was customary for seniors to delegate tasks to juniors, and if the opportunity arose, they would assign all the work. This practice prevailed in the newspaper industry a century ago and continues today. However, Abul Mansur Ahmad perceived this perspective as a blessing. He developed a habit of shouldering the "big load." His time at Mohammadi was beneficial, with extensive working hours allowing him to acquire knowledge and learn new skills. He thought it was necessary to utilize every opportunity to its fullest extent, finding satisfaction even in meticulously proofreading articles. He wrote, "Proofreading is a unique art. In this task, skills and expertise are more important than mere knowledge."

He worked at "Mohammadi" for nearly one and a half years, but his tenure there abruptly ended, much to his surprise. The reasons for this sudden termination were not disclosed and appeared trivial. Without any official reprimand or clear explanation, he was handed his dismissal notice. Soon after, Abul Mansur Ahmad discovered that his assistance and advice to Maulana Abdullahil Kafi and Maulana Abdullahil Baqi, who worked at the "Satyagrahi" newspaper, were perceived as unacceptable by the authorities. Reflecting on these circumstances in his autobiography, he explained, "I wouldn't have provided support to Satyagrahi if I knew it would be considered a fault… Because it was impossible to sustain financially without the job, which paid Tk50." By that time, he had agreed to marry, and the wedding date had been fixed.

Abul Mansur Ahmad's third job was at The Muslim newspaper, a position he secured upon Maulana Abdullahil Kafi's request to Maulvi Mujibur Rahman. With an advance salary of Tk 65, he was allowed to visit his village and prepare for his marriage. He worked for The Muslim for four years. In his account of this experience, he reflected on the etiquette lessons he learned from Maulvi Sahib: "Do not criticize or condemn in a way that disregards etiquette and politeness." Additionally, he received recognition for his efficiency in this institution. The authority decided to publish the Bengali weekly 'Khadem' solely based on his efficiency. He was entrusted with the responsibility of editor of the weekly.

He demonstrated immense foresight in a sensational incident involving the conversion to Islam of Allahabad-based public figure Swami Satyadev. Upon Satyadev's arrival in Calcutta, he was welcomed with a money garland. While all Muslim newspapers supported this gesture, 'Khadem' stood in opposition. Abul Mansur Ahmad argued, "Supporting a non-Muslim accepting Islam is derogatory for Islam and the Muslim society, as such a virtuous person enhances the strength and dignity of 'Islam' and the Muslim society." This opposition sparked a protest against 'Khadem,' and a complaint was filed against Abul Mansur Ahmad to Maulvi Mujibur Rahman. Although Maulvi Sahib respected his viewpoint, he advised Abul Mansur Ahmad to consider public opinion respectfully. Abul Mansur Ahmad chose to remain silent. After a few days, events unfolded in a way that proved Abul Mansur right.

Mahiuddin (Swami Satyadev's Muslim name) returned to Allahabad with five lakh taka collected from the region and reverted to his previous religion, Hinduism. Abul Mansur Ahmad reflected, "The faces of the greeters were stained, whereas my supporters displayed smiles. However, the victory brought tears to my eyes as I reflected on the wretchedness and foolishness of my own society."

The first phase of his journalism career came to an end in December 1929. Notably, during this phase, preparations for his future role as an editor became evident. "Dress rehearsals" were underway for his upcoming editorship, which would come to fruition in the days to come. In publications like 'Soltan,' 'Mohammadi,' 'The Muslim,' and 'Khadem,' he began to groom himself for this role. He particularly cultivated traits such as intellectual curiosity, shouldering responsibility, and a thirst for knowledge, which played a crucial role in molding him into a successful and meaningful editor in the later stages of his journalistic career.

Abul Mansur Ahmad's second phase of journalism began in December 1938 after a gap of nine years. During this phase, he emerged as a full-fledged editor. 'Dainik Krishak' was published as the mouthpiece of the 'Krishak Praja' movement under the initiative of Nikhil-Banga-Krishak-Praja Samity. Humayun Kabir served as the Managing Director, and the board of directors included prominent figures like Maulana Shamsuddin Ahmad, Maulana Syed Nausher Ali, Nawab Syed Hasan Ali, Khan Bahadur Muhammad Jan, and Dr. R. Ahmad. Subhas Chandra Bose, the President of the Congress Party at that time, patronized this initiative. Abul Mansur Ahmad served as the editor, with a salary of two hundred taka and a table allowance of fifty taka.

Abul Mansur Ahmad reflected on is experience with the newspaper 'Krishak'. He worked diligently, and 'Krishak' quickly gained respect and popularity among the general public shortly after its inception. Maintaining unwavering commitment to ideals, an independent outlook, and impartial criticism, 'Krishak' earned a significant reputation. However, it faced challenges. Despite its initial success, 'Krishak' encountered difficulties and was on the brink of closure. Humayun Kabir stepped down from the position of Managing Director. At this critical juncture, Abul Mansur Ahmad came to realize several key points:

Running a daily newspaper requires substantial capital, a consideration overlooked by the leadership of 'Krishak'.

Newspapers have transitioned from a missionary endeavor to a business industry.

Ensuring the financial viability of a daily newspaper necessitates substantial investment.

After Humayun Kabir, Khan Bahadur Muhammad Jan took over as the Managing Director of 'Krishak.' Being a non-Bengali, he lost interest in the job within three to four months. Following him, Hemendra Nath Dutt, also known as H. Dutt, assumed leadership. With prior experience as Managing Director at the Calcutta Commercial Bank and other institutions, he was seen as a suitable candidate to turn 'Krishak's fate around.

Abul Mansur Ahmad recounted, "I arranged for fans for the compositors (as promised earlier). Many profitable newspapers didn't do that at that time. They ridiculed my effort." However, differences in policy arose within 'Krishak.'

A heated debate ensued in the cabinet over the proposed Intermediate Education Bill, which, if passed, would transfer control of the matriculation examination from the University of Calcutta. While most major newspapers, particularly those aligned with the Congress Party, vehemently opposed the bill and worked to build consensus against it both within and outside the parliament, 'Krishak' stood in support by writing editorials favoring the bill.

This stance led to Abul Mansur Ahmad's eventual resignation amid protests with the Managing Director of the paper. During this time, a fundamental question emerged: who holds the final authority in a newspaper, the owner or the editor? Abul Mansur Ahmad argued in favor of the owner's authority.

In this context, he expressed, "I likened journalism to a profession akin to law practice. It's not a calling like missionary service. Similar to a lawyer who handles cases irrespective of the guilt or innocence of the client, journalists also receive assignments from various entities such as the Congress, Muslim League, Hindu Mahasabha, or others. Journalists, likewise, fulfill their duties for their salary. They must remember that their independence should not be compromised beyond their journalistic obligations. For instance, if one supports the Congress, they should refrain from accepting roles that require writing against it. If they do, they must be prepared to do so."

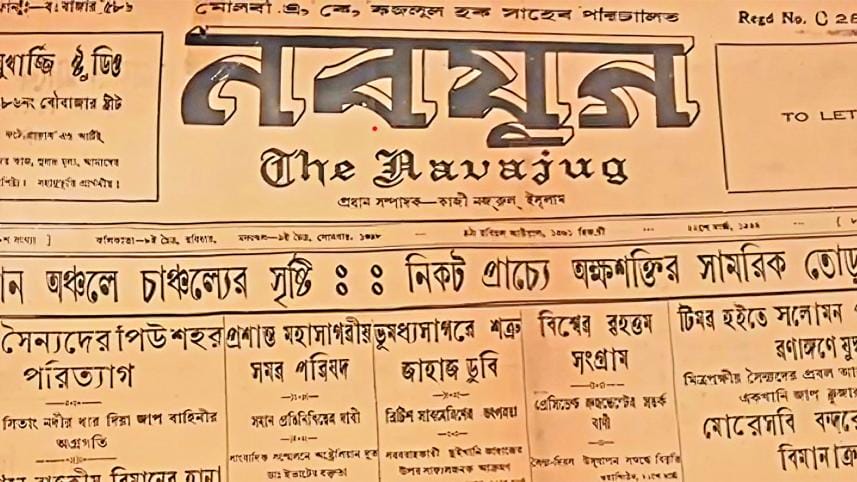

In October 1941, Abul Mansur Ahmad began the third phase of his journalism career with the launch of 'Nabajug'. Rather than accepting the title of editor, he assumed the role of a 'shadow editor'. His remuneration was set at three hundred takas. Kazi Nazrul Islam was appointed as the editor of 'Nabajug', which was A. K. Fazlul Huq's daily newspaper. Ahmad's reasoning for declining the title of editor was his desire to work impartially for newspapers of any ideology.

However, for the greater cause of 'Nabajug,' he could not remain steadfast in his principle. Drawing from his experience with 'Krishak,' he came to understand that a newspaper should operate according to the owner's perspective. He stated, "Huq's political successes and failures were closely tied to the existence of 'Nabajug.' The survival of 'Nabajug' wasn't just my concern; the livelihoods of over a hundred employees at 'Nabajug' depended on it. Except for two or three individuals, all of them were Muslims. If 'Nabajug' were to fail, their livelihoods would be at stake. I understood this from my recent experience with 'Krishak.' That's why Huq's political line has to be succeeded for 'Nabajug," and I was writing editorials on this consideration."

Due to differences with Hemendranath Dutt, Abul Mansur Ahmad left 'Krishak.' However, Dutt later joined 'Nabajug' as the Managing Director. The beginning of this new role was marred by an unexpected incident on the first day. An unpleasant event unfolded during a brief conversation. Hemendrababu got angry and exclaimed, "Are you trying to attack me? I will inform the concerned authority." Saying this, he stormed out but tragically, he fainted on the staircase. This event prompted the creation of two verse dramas titled "Hemendro Bodh Kabyo" (The Poetry of Hemendranath's Death) and "Hemendro-Mansur Sangbad" (The Events of Hemendranath and Mansur), featured in the well-known satirical magazines 'Voteranga' and 'Avatar'. As a result of these events, Duttbabu became even more deeply entrenched, and conversations and relations between the two key figures at 'Nabajug' ceased entirely. Within a few days, when Abul Mansur Ahmad was on vacation at his village, he received a telegram from Kazi Nazrul Islam stating, "Your services are no longer needed." This telegram marked the end of his career in journalism in the third phase.

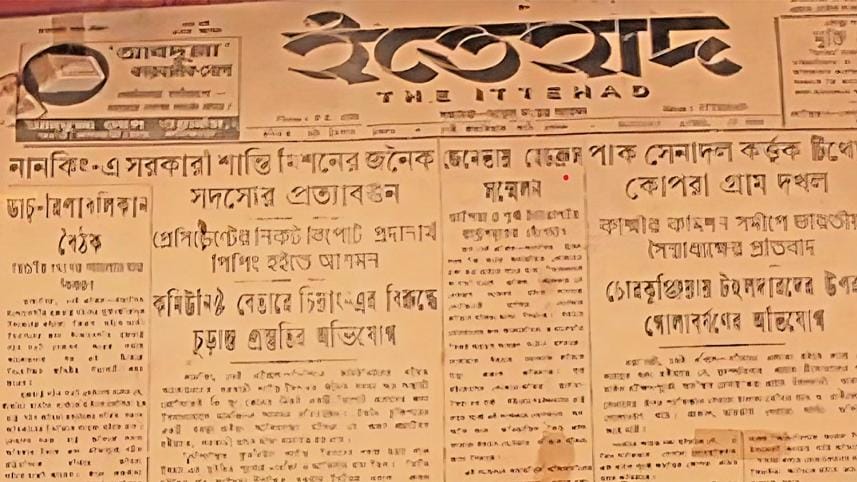

Abul Mansur Ahmad's fourth and final active and professional journalism career began in January 1947 when he assumed the role of editor at the "Ittehad" newspaper for a salary of Tk 1000. Reflecting on his experience, he remarked, "Throughout my entire journalistic career, this period brought me the most happiness, ease, and dignity. Journalistic independence was upheld here, and I benefited greatly from the excellent management of Nawabjada and Farukul Islam." However, this period of contentment was short-lived. As events unfolded, India was partitioned into two independent nations, India and Pakistan, with the British returning to England, leaving the subcontinent divided.

In the following two decades, Abul Mansur Ahmad sustained his journalistic spirit by working as a columnist. Although "Ittehad" did not gain access to East Pakistan, its influence on journalism in the 1950s remained unparalleled. The impact of this newspaper extended across various facets of journalism, from the naming conventions of thriving newspapers to their editorial prowess, development strategies, layout designs, language usage, policy formulation, paper quality, design aesthetics, and distribution arrangements—all of which bore the imprint of 'Ittehad.'

Upon the centenary of Abul Mansur Ahmad's journalism career, it became clear that he not only mesmerized his contemporaries but also stirred profound admiration and respect. While conventional education often neglects his achievements, his journalistic and editorial legacy persists in every word he wrote. Essentially, it stands as a beacon of wisdom and inspiration, akin to a precious gem that can empower present-day journalists and editors to nurture their skills and viewpoints towards their goals.

Kajal Rashid Shahin is a Journalist, Writer, and Researcher.

The article is translated by Saudia Afrin and Priam Paul

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments