Tamam Na Sud

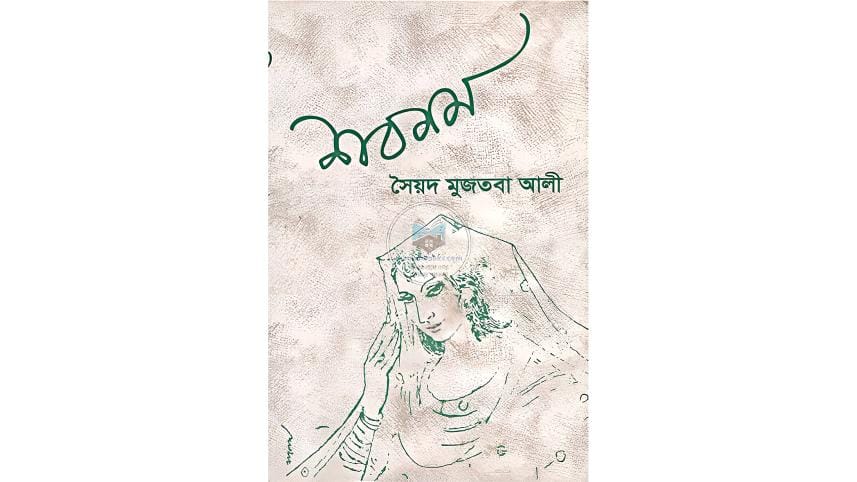

Tamam na sud or 'Not the end'! There could not have been a better ending of a captivating romantic novel like Shabnami. These three words at the end of the book ignite a plethora of emotions in the mind of the reader as they start to identify themselves as one of the two protagonists – Shabnam or Majnun and even start to imagine a sequel that will not end in a heart-wrenching tragedy. This way the readers embark on an ever-lasting journey with the book.

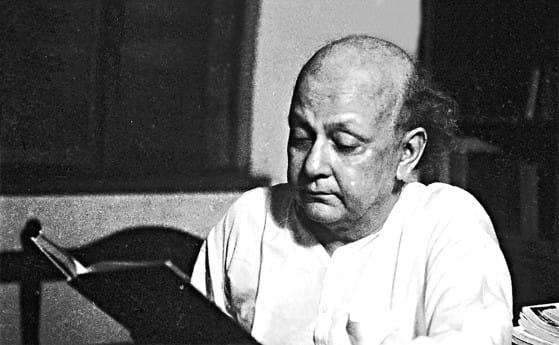

Syed Mujtaba Ali did not venture into fiction writing much. Despite producing a huge body of work, he had only three novels to his name, Obissasyo (1955), Shabnam (1960) and Tulonaheena (1972). Of the three, Shabnam stands out to be the most powerful one in terms of its story outline, the building of the characters, the ending and the philosophical quest of the two protagonists—a feisty independent young Afghan woman and an erudite Bengali teacher teaching in Kabul.

On another count Shabnam can be seen as groundbreaking in Bangla literature. There are only a few Bangla novels written by men where women are cast as the central figures. Even though there were two protagonists in Shabnam, Ali did not hesitate to put Shabnam in the lead.

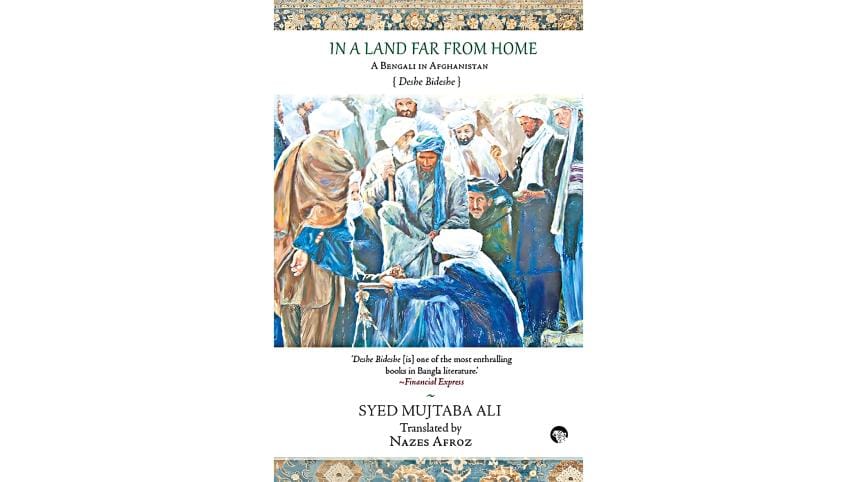

The love tragedy between Shabnam and Majnun unfolded in the backdrop of a tribal rebellion against the modernizing king Amanullah that set of an unimaginable degree of lawlessness and chaos in Afghanistan at the end of the 1920s. But that history did not encroach on the story unnecessarily; it came only as much it was needed. Mujtaba Ali himself lived through that turbulent time in Kabul and nearly died there starving. His memoir of the period became his first book—Deshe Bidesheii (1948-49). There is an oblique reference to the book in Shabnam too.

On another count Shabnam can be seen as groundbreaking in Bangla literature. There are only a few Bangla novels written by men where women are cast as the central figures. Even though there were two protagonists in Shabnam, Ali did not hesitate to put Shabnam in the lead. Shabnam is poetry personified, as she is aware of Sufi mysticism. She is hopelessly in love with the 'foreigner' Majnun but she is not the demure damsel. She is the one who initiates the romantic liaison and then she takes it to the next level by visiting his home alone. Even when there was looting and lawlessness all around, she did not stop visiting him. She was ready to take a few lives to do that, "I would have killed every devil. Any number—if needed. I held the revolver ready under the burka. If anyone stood in front, I would have shot him. No questions asked. I would have walked over their dead bodies to come to meet you."iii She is the one who kisses Majnun first and she decides to arrange an instant marriage with him fearing that the political pandemonium would linger. She floats in the clouds of poetry yet she expresses her strongest opinion on how to change the society, "Is society a tiger or a lion that we have to confront it with pistols and guns? Society is like a spirited stallion. Feed it and then mount. If it misbehaves, poke it with the spike of your boots. Whip it if it becomes worse. When it becomes unmanageable, then use the pistol. Buy a new horse—create a new society."iv

My tryst with Shabnam started, long before I took up its translation, in the transition year of my teenage into adulthood. At that delicate age, one tends to expect a happy ending of such an intense love story that revolves around only two characters who engage in poetry, aesthetics and philosophy all through. As this unlikely love flowered breaking the barriers of culture and language when Afghanistan was hurtling towards anarchy. The tragic ending created such a sadness and hollowness in me as a reader that I could not read that book for another decade or so.

I laid my hands on Shabnam for the first time possibly a year after I read Ali's magnum opus Deshe Bideshe, that established him as one of the most important and charismatic writers of Bangla literature in the second half of the twentieth century. So the backdrop of Shabnam was already known to me. I did not have to struggle to understand the social and political milieu against which Shabnam was written. But the reading of Deshe Bideshe before taking up Shabnam also raised a question: was that an autobiographical novel?

The story of Shabnam did not happen in Ali's life for sure but what if he had seen or heard about a love story where one of the lovers simply disappeared like Shabnam as my friend commented from his own life experience? I would say that was most likely the case.

Readers of Deshe Bideshe and Shabnam would always find uncanny similarities between Ali himself and Majnun – the male protagonist he created. Like Ali, Majnun came to teach in Kabul from the district of Sylhet in East Bengal in undivided India. One of the central figures of Deshe Bideshe is Abdur Rahman – Ali's most trusted servant, his "major domo, chef-de-cuisine and handyman – three in one"v who apparently would "do all the bidding for you, from polishing your shoes to killing your enemies"vi. Abdur Rahman became "my Harfan-Moula, my Jack of all trades"vii. In Shabnam, Majnun's servant too is called Abdur Rahman who was undertaking similar tasks!

In Shabnam Ali created another trusted aide to Shabnam, Topol Khan who happened to be Abdur Rahman's cousin. These two, Abdur Rahman and Topol Khan, became the go between the two lovers and help them in their assignations. They also agreed to be the happy witnesses to their instant secret marriage in the house of Majnun while the city of Kabul was descending into a chaos.

Hence, the Bengali readers always speculated if Shabnam was actually an autobiographical novel. The readers liked to believe that Ali had a romantic liaison with an Afghan woman while living in Kabul between 1927 and 1929. But Ali did not leave any suggestions of such a relationship in any of his writing. If we take Deshe Bideshe as a true and authentic eye-witness account and a chronicle of a crucial juncture of modern Afghan history, then as readers, we are left with the only conclusion that Shabnam is indeed a work of pure fiction. Ali's nephew and former Bangladeshi senior diplomat, Syed Muazzem Ali told me that he had asked his uncle if someone akin to Shabnam ever existed during his time in Kabul. In his reply Ali had said, 'Nephew, try to stretch your imagination!' In relation to this speculation, Ali himself wrote in one of his pieces that during his stay in Kabul, his had regular interactions only with two women – one used to supply milk to his house and the other was the laundress and both were above sixty.

After my translation of Shabnam came out in 2024, a close Afghan friend wrote the following to me after reading it, 'Finished the book but had an unstoppable feeling throughout that this had happened during my life time because so many people disappeared and never returned including two people in my extended family and many more known to me.' This comment by my friend suddenly sowed the seed of an idea in my mind about the genesis of the story of Shabnam.

Most readers of Ali would know that he was a master at picking up nuggets of stories around him and finessing them as highly readable and outstanding tales that germinated from real-life experiences. Stories from Chacha Kahini, or other stories like Tuni Mem, Nona Pani, Nona Jol and many such pieces are testaments of this genre of his writing.

The story of Shabnam did not happen in Ali's life for sure but what if he had seen or heard about a love story where one of the lovers simply disappeared like Shabnam as my friend commented from his own life experience? I would say that was most likely the case.

By reading Deshe Bideshe, we know how deeply Ali bonded with the elite class in Kabul and even befriended many from a number of diplomatic missions. Some of these friends and their exploits found mentions in Deshe Bideshe. We even read how his Pashtun colleague-turned-friend Dost Muhammad simply left the city leaving a letter for him saying he had picked up the gun and was going to fight the bandit leader Bacha-e-Saqao on behalf of his king Amanullah. Ali never heard of him after that. Ali wrote about Dost Muhammad's charm and witticism, especially among the women in the diplomatic circles. So, could Dost Muhammad be one of the lovers who disappeared? Or any other person whom Ali got to know during his stay but never mentioned them in Deshe Bideshe? Such a possibility is highly likely.

There may be another lens through which Shabnam can be read. One could take it that Ali decided to tell the story of a country, that he fell in love with, through allegory. His fondness, deep empathy and endless love for Afghanistan was evident in every chapter of Deshe Bideshe and also in Shabnam. Could he have painted the picture of Afghanistan as Shabnam – a most beautiful woman (he repeatedly talked about the beauty of Afghanistan in his writing) who was fiercely independent (as Afghanistan is)? He lamented so many times that how Afghanistan had been searching for peace that had been eluding her for centuries. Ali himself was there in Kabul when there were glimmers of hope, but that vanished into thin air in no time. Ali did not go back to Afghanistan after his stay there for a year and a half. He remained estranged with the country he loves so much. Hence, in a way he might have taken the role of Majnun and depicted Afghanistan as Shabnam and continued searching for her, in vain, for the rest of his life.

Notes:

i Translated by Nazes Afroz, published by Speaking Tiger books, India in 2024

ii Translated by Nazes Afroz titled In a Land Far from Home/A Bengali in Afghanistan published by Speaking Tiger Books in 2015

iii P 100: P 103: Shabnam (2024) Speaking Tiger Books

iv P: 74: Shabnam (2024) Speaking Tiger Books

v P 103: In a Land Far from Home/A Bengali in Afghanistan (2015) Speaking Tiger Books

vi P 101: In a Land Far from Home/A Bengali in Afghanistan (2015) Speaking Tiger Books

vii P 101: In a Land Far from Home/A Bengali in Afghanistan (2015) Speaking Tiger Books

Nazes Afroz has worked as a journalist for more than four decades in print and broadcast media,

18 of which for the BBC, covering current affairs spanning South, Central and West Asia in the capacity of a producer and later as a senior editor. Currently based in Kolkata, he writes in Bangla and English for a number of newspapers and websites. Apart from co-authoring a cultural guidebook on Afghanistan, Afroz has translated Syed Mujtaba

Ali's Deshe Bideshe into English under the title In a Land Far from Home: A Bengali in Afghanistan (2015) Joley Dangay under the title Tales of a Voyager (2023) and Shabnam (2024), all published by Speaking Tiger Books in India.

As a passionate documentary photographer Nazes has held several exhibitions in countries across three continents from 2015 including his work on the Kabuliwalas of Kolkata.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments