Sharing of Ganges water: What looms after 2026?

In 1976, a mass procession led by a nearly 80-year-old peasant leader, Maulana Bhasani, from Dhaka to the Indo-Bangladesh Border drew huge attention from national and international media. It demonstrated a profound sense of deprivation among the people of Bangladesh against the unilateral operation of the Farakka Barrage by India, which allegedly killed the Ganges River and unsettled the lives of millions of Bangladeshis living downstream of the Ganges.

The Farakka issue quickly became a perennial irritant in Indo-Bangladesh relations. An internationally renowned expert, R.R. Baxter, was hired to prepare a document assessing Bangladesh's claims. Based on this assessment, a White Paper was published, and the issue was raised by Bangladesh in the UN General Assembly in 1977. Consequently, a five-year temporary agreement was concluded; however, it soon faltered, followed by a weaker legal arrangement (MoU), which raised more controversy on both sides of the border.

I went to SOAS, University of London in 1994 with a Commonwealth Scholarship to pursue a PhD on the international legal aspects of this conflict. Based on a literature review, I found that there were examples of accommodating competing interests of the basin states of a shared river by observing the principles of international watercourse (or river) law. So, why had Bangladesh and India failed to do so, despite many years of protracted consultation and negotiations?

I tried to find answers to this question. In the absence of any "global codification" by intergovernmental bodies, the search for international law centered on applicable "customary rules." The International Law Commission rapporteur assigned to codify those rules on the utilization of shared rivers into a global convention had already agreed in 1994 on the existence of such customary rules. However, there were other versions as well; a notable one was the 1970s proceedings of the Asian-African Legal Consultative Committee, comprising, among others, India, Pakistan, and later Bangladesh, which recorded its failure to agree on most of the drafts of customary rules placed for its consideration.

It therefore appeared doubtful whether the global customary rules of international watercourse law were "global" at all, or whether they, like some other branches of international law, were based almost entirely on European and American practice. For that reason, was their application in other areas, including in South Asia, still a debatable issue, and did this confusion have any impact on the resolution of the Ganges water dispute?

2

A closer look at the South Asian practice, however, reveals an encouraging picture. It shows that from an early period, most of the countries in this region recognized at least one applicable international law principle: the principle of equitable sharing or equitable utilization. Occasional references were also made to the principle of no harm, although it has implications that do not fully conform to the equitable principle.

For example, the equitable utilization principle provides for numerous factors of equity such as river condition, existing uses, dependent population, available alternatives, and the impact of the project, which can be used to assess whether the diversion by the Farakka Project was equitable or reasonable. However, this principle has not settled the hierarchy of those factors. Therefore, by selectively emphasizing those factors, arguments both for and against any planned measure such as the Farakka Project could be made.

But in accordance with the no harm principle, it would be very difficult to support such a project considering its harmful impact on the downstream areas.

Interestingly, the relation between these two substantive principles has not been fully resolved even in the global codification of international watercourse law in 1997. The 1997 Watercourse Convention simply suggests resolving disputes based on both these principles and through compliance with a set of procedural obligations such as information sharing, consultation, and negotiation, etc.

However, there have been two important developments in the last few decades which, among other things, aim to place more emphasis on ensuring protection from potential harmful impacts of any planned measures on a shared river, specifically emphasizing the no-harm principle. The first is the emergence of the concept of treating an international watercourse as an indivisible natural resource, thus requiring a basin-wide approach for the utilization, development, and management of an international watercourse. The second is the growing legal recognition of the right of the river as a living entity, and therefore giving due regard to the environmental implications of the utilization of a watercourse. These require a much broader, holistic, and rational approach to dealing with international watercourses and provide wider opportunities for addressing the long-standing conflicts on the utilization of international watercourses.

With added optimism based on these developments, I recently embarked on updating my PhD (awarded in 1999) thesis. As the principles of comprehensive data sharing, integrated water resource management, and protection of the ecology of the watercourse continue to solidify, their importance in the renegotiation of the latest Ganges treaty of 1996, set to expire in 2026, has grown significantly.

The title of the thoroughly updated version of my PhD is "Sharing Ganges Water, Indo-Bangladesh Treaties, and International Law," and it was published (under my academic name Md. Nazrul Islam) in February 2023 by University Press Limited.

3.

This book has compared the experience of negotiation of the Ganges agreements to the contemporary development of international law to determine the extent to which the basin states of the Ganges were prepared to learn from the advances in international law. It has also attempted to understand whether the Ganges dispute reflected non-compliance or a narrow application of international law.

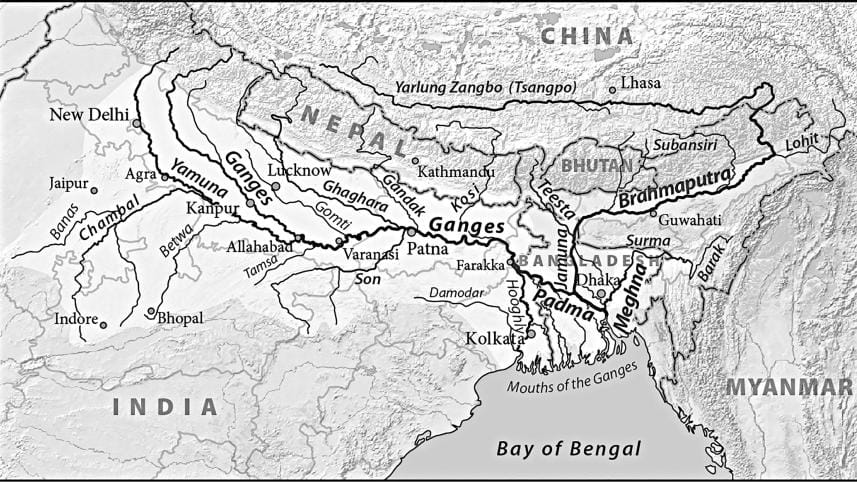

First, it assesses whether the information exchanged between India and Pakistan (predecessor of Bangladesh before the latter's liberation in 1971) during the early stage of the planning of the Farakka project was adequate to resolve the amount of water of the Ganges that constituted an equitable share for each country and the extent of the impact of the project. It should be mentioned that the irrigation and hydroelectric projects of the upper reaches of India and their impact on the availability of water to be shared between the Farakka project and Bangladesh at the downstream area were kept outside the purview of negotiations on the Ganges issue. What were its implications, and how did the international law developed at that time entertain this question?

Second, the later agreements, including the 1996 Ganges Treaty (between Bangladesh and India), were premised on this limited information sharing and made an allocation of the Ganges water at an extreme downstream point between the Farakka project and Bangladesh without provisions for exchanging information on the use of Ganges water in the vast upstream areas in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in India. It was claimed that these arrangements were based on equity, fairness, and no harm. The crucial question raised in my book is, can the arrangement of sharing the 'residual' flow of a river (water left over after the unlimited upstream diversion) be made equitable or fair? Or ensure no harm to the downstream country? What were the rules of international law on such issues?

Third, in the case of the Ganges, the issue appeared more complex, since the river actually originated further upstream in Nepal. Can Nepal, therefore, be ignored in any sharing arrangement of the Ganges at its downstream point? How would it impact the sharing arrangement then? How different could it have been with the participation of Nepal?

If we examine the experience of implementing the Ganges agreements from 1977 to the present, it provides answers to many of these questions. The fact is that the Ganges negotiation began and continued on a faulty legal premise. It focused solely on the competing demands and uses in the downstream Ganges without linking these with the upstream uses of the river. The resulting agreements were unique in many respects. They were short-term or fixed-term, primarily centered around the Farakka project, and focused solely on the economic use of the Ganges, neglecting key environmental issues.

As a result, the agreements, including the long-term 1996 Treaty, have failed to fully achieve their goals of equity and no harm. The joint river commission assigned to monitor the implementation of the 1996 treaty meets irregularly, and the state parties have shown no interest in correcting its deficiencies. Regular complaints have been raised from both sides about the poor performance of the treaty.

Furthermore, negotiations on the sharing of other transboundary rivers (such as the Teesta) have not learned from the Ganges experience and have thus failed to produce any significant advancements. Most of these negotiations have followed the Ganges pattern, excluding other basin states, limiting data sharing and consultation to water availability at the tail end of the river, disregarding the need for maintenance of environmental flows, and failing to establish a powerful and autonomous river commission.

The 1996 Ganges treaty will expire in 2026. It also provided for conducting negotiations for sharing the water of other common rivers based on equity and no harm principles. Unless it is renewed, there will be no negotiated arrangement for Ganges water sharing or agreed basis for negotiations on other rivers in the post-2026 period.

A modified Ganges Treaty involving all of its basin states (Nepal, India, and Bangladesh) should be concluded before it expires in 2026. It is high time to learn the lessons of the past and thus reposition the course of future negotiations, taking due account of the recent developments in international law that inspire integrated basin-wide development of rivers.

4.

Bangladesh and India (along with all the basin states of South Asia) should have a wider vision to understand that integrated, multilateral, and basin-wide water resource management would be a much better approach to accommodate the various needs of the basin states of any international river and to ensure its adequate protection. They need to understand that the equitable utilization or no-harm principles cannot be translated into reality without the equitable participation of all the basin states, comprehensive data sharing (including through participatory EIA) on all the actual and potential water uses, negotiated arrangements on that basis, continuous monitoring, and efficient conflict resolution mechanisms. In accomplishing these, they should respect and embrace the customary rules reflected in the 1997 Watercourse Convention and other relevant instruments. They should also consider the recent increasing focus on related environmental obligations, human rights aspects, and the need for an efficient institutional regime, as elaborated in the 1992 UNECE Watercourse Convention (global participation opened in 2015) and the 2004 ILA Berlin Rules, and as followed in some water-stressed regions in Asia and Africa such as the Mekong and Senegal basins.

As a vulnerable downstream region to nearly 54 rivers, Bangladesh, in particular, should take the lead by becoming a party to Watercourse Conventions. It should also demand the application of existing international environmental agreements like the 1992 Convention on Biodiversity and the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which contain corresponding provisions on the use of international watercourses. Bangladesh could thus influence other co-basin countries to realize that watercourses are precious natural resources that need to be utilized, developed, and managed through an efficient and comprehensive arrangement covering all the uses and involving all the stakeholder States. This realization is crucial for the long-term benefit of the region and the sustainability of the dependent ecosystems.

Dr Asif Nazrul is Professor and Chairman, Department of Law, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments