Sacrificed for Development

After the creation of Pakistan, the nascent state embarked on vigorous projects to industrialise both parts of the country. Pakistan required substantial energy for its industrialisation and ambitious development projects. Various government records highlight how acute the energy demand was to operate the new mills and factories. Factories in the late 1940s and 1950s often had to undergo forced shutdowns due to power shortages. The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) emerged as a favourable option for the state of Pakistan when it came to constructing power plants. This essay examines two such large-scale development projects in postcolonial Pakistan and their consequences for the Adivasis in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

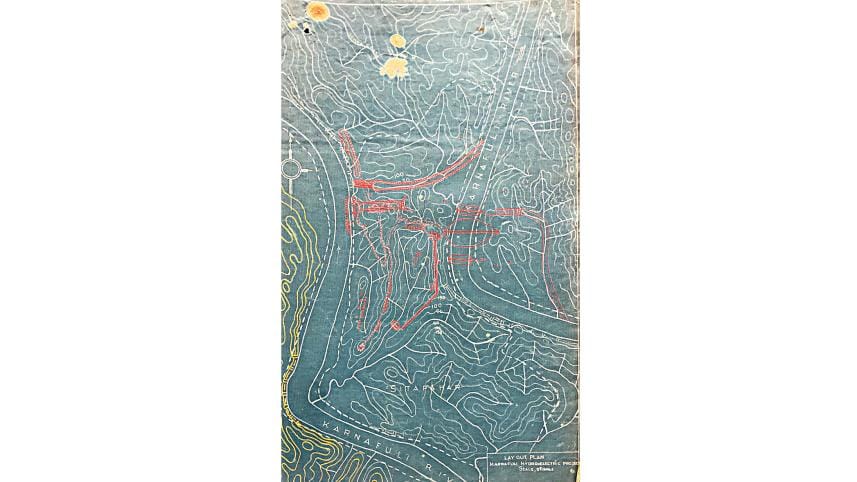

The state was already aware that the British government had planned a hydroelectric project on the Karnaphuli River in the CHT. In 1906-07, the British colonial government first inspected the Karnaphuli River to assess the feasibility of constructing a dam for hydroelectric power generation. However, little is known about that investigation. In November 1922, Mr. Grieve, a temporary engineer, was appointed to further examine and identify a suitable site for the hydroelectric dam. Mr. Grieve conducted a comprehensive investigation and submitted a detailed report to the relevant department. His findings suggested that approximately 28,000 to 40,000 KW of electricity could be generated upon the project's completion. Further investigations were carried out in 1945 and 1946, led by E.A. Moore, the superintendent engineer of the East Bengal Circle. The British colonial government was close to implementing the project, having collected detailed meteorological and other essential data. The Bengal government had already proposed the utilisation of electricity in various mills and factories in East Bengal and had outlined the departments responsible for the dam's construction, along with an estimated project cost. However, due to political upheaval in the 1940s, the British colonial government could not proceed with the project.

Following the establishment of Pakistan, the state revived the Karnaphuli hydroelectric project in 1948. In addition to local engineers, the Pakistan government hired J.L. Savage, an American engineer, to expedite the project's construction. The Karnaphuli hydroelectric scheme was officially sanctioned in June 1951, with the expectation that electricity would be available for sale by the end of 1960. The project was anticipated to deliver an average continuous power output of 40,000 KW during the monsoon and 20,000 KW at other times. Construction of the Karnaphuli hydroelectric scheme began in 1957 and took almost five years to complete.

Despite conducting thorough investigations into the project's meteorological, flood control, and financial aspects, the government did not consider it necessary to consult the Adivasis or indigenous people, who were the primary residents of the area. Government departments were aware that a significant number of people would be affected by the construction of the Karnaphuli hydroelectric dam at Kaptai, Rangamati, a district within the CHT region. In the 1950s, there was a discussion about establishing the headquarters of the CHT at Kaptai, Rangamati. However, concerns about the potential inundation of large land areas and environmental deterioration due to the dam's construction led many government officials to oppose this decision. Officials also anticipated large-scale violent protests following the dam's construction. The state recognised that, beyond the inundation and displacement of many people, the affected population's livelihoods would be jeopardised. The government was aware of the potential food scarcity. Despite this, the rehabilitation plans for the affected people were impractical and narrow in scope. The then-chairman of WAPDA suggested: "There is no need to settle the affected persons on flat land to enable them to undertake plough cultivation of paddy and other food crops. They should be settled on the steep slopes of hills where they can grow fruit trees and tea and earn enough money to live. Food can be imported for them either from the rest of the province or from abroad if necessary, and they can live quite happily and comfortably."

In the government's confidential report, the high officials noted that, regardless of what might have happened, they could not alter the plan. The confidential report continues:

"The chief secretary feels that the rehabilitation plans and programme already settled and approved need not undergo any material change or disruption, except that care should be taken to avoid constructing any valuable installations (V.I) such as tarred or concrete roads, model town, official headquarters or otherwise hospitals, schools or colleges, the Rajbari of the Chakma chief, and so on below the level up to which water would rise in the event of a high flood when the dam is ultimately raised another 13 ft…"

The construction of the Kaptai dam was a massive blow to the Adivasis of the CHT. It displaced more than 100,000 Adivasis, constituting 25% of the region's population. The government's rehabilitation sites were further inundated between 1965 and 1966. Over 40,000 Adivasis had to flee the country barefoot, seeking refuge in Tripura, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh. It is not that the state was unaware of the possibility of further inundation after the project's completion; the state simply remained silent. The government's confidential report provides reflections on this issue:

"The 10,000 acres of flat land reserved in Kassalang for rehabilitation shall also go under water, which means that rehabilitation work in this region must stop. There is no question of planning a model town there. It is scheduled to be taken up next year… There should be no rehabilitation below 133 R.L. The majority of the rehabilitation area explored and allotted by us is below 133 R.L… All these have been abandoned. The vast plain between Mahalchari and Panchari will go under water and has to be abandoned."

After the Partition, the Karnaphuli hydroelectric scheme was implemented in a very short time. Construction began in 1957 and was completed by 1962. A significant portion of arable land, arguably the most fertile in the CHT, was submerged. It is estimated that around 40% of the CHT's agrarian land was inundated due to the Kaptai dam's construction. A government confidential report discusses the difficulty of making the rehabilitation plan in such a short time:

"It is impossible to alter the rehabilitation plans so drastically at such short notice without taking the people into confidence, and the psychological effects of these changes are going to be colossal and catastrophic. The coffer dam has been closed, and next year water will rise up to 120 ft… People have, therefore, got to be evacuated somewhere. Even if they are settled on steep hill slopes and persuaded to grow fruit trees and tea, the scheme is not likely to take shape, be approved, and commence for another two years, and will begin yielding results only after 7 or 8 years. During this period, a population of nearly a lakh and a quarter of persons (300 sq. miles of a most densely populated area)…"

Apart from the Karnaphuli hydroelectric scheme, the fledgling postcolonial state undertook various development projects. One significant project was the construction of the Karnaphuli Paper Mills at Chandraghona in the CHT. The Adivasis of the CHT had to endure a double blow from these two massive development projects in the 1950s— the Karnaphuli Hydroelectric Project Scheme and the Karnaphuli Paper Mills. Both projects displaced a large number of Adivasis and exhausted their livelihoods. Even the deputy commissioner of the CHT was dissatisfied with the extensive land acquisition by the state's Development Department. In his letter to the commissioner of the Chittagong division, he writes:

"The Development Department of the Government of Pakistan has been negotiating with me for some time for land in Chandraghona for a Paper Mill. Their requirements were vastly more at the end than they were expected to be at the outset. In fact, when the commissioner and I visited the area last year, we thought they would need practically one-quarter of what they now demand. I offered them double the original area, but they wanted the whole, which included the bazar, a supplies Godown, the Police Station, the Post Office, the C and W.D., an Inspection House, and a number of private dwellings and fields. In fact, they demanded the whole of Chandraghona excluding the Baptist Mission Hospital."

The large-scale land acquisition by Karnaphuli Paper Mills was not properly compensated. The Mills evicted and dispossessed a large number of Jummias from their fertile jum land, leaving them in a vulnerable condition. These poor Adivasis were not adequately rehabilitated. The Karnaphuli Paper Mills authority allocated only a nominal amount of money to the 'tribal' chief. However, the jum cultivators received no compensation. Furthermore, the Labour Commissioner of East Pakistan instructed the Karnaphuli Paper Mills authority not to employ 'tribal' people from the CHT. The government also proposed transferring Chandraghona from the CHT region to the Chittagong district to exploit the area more conveniently.

In its proposal, government administrators suggested repealing the Chittagong Hill Tracts Regulation of 1900, which was passed by the British colonial government. This Regulation restricted the influx of Bengali people into the CHT while isolating the Adivasis from other parts of Bengal. Willem van Schendel observes, "Far from regional autonomy or the protection of 'tribal' rights (as some would have it), it marked the onset of a process of 'enclavement' in which the hill people were denied access to power and were subordinated and exploited directly by their British overlords." Nevertheless, the Adivasis believe the CHT Regulation of 1900 offered them some protection. The abolition of this Regulation led to a significant influx of the Bengali population into the CHT. However, when the government policymakers proposed the "Proposal for exclusion of C.H.T.s from the category of tribal area," they did not consult the local people. For the policymakers, the region was extremely poor and backward, and the Adivasis lacked political training. They believed the Adivasis lacked political or administrative institutions. Before 1961, there was no district or local board union. They noted that the Adivasis still maintained 'tribal' habits and traditions. For them, before the construction of the Karnaphuli Hydroelectric Scheme, the Adivasis had practically no contact with the outside world. The top government officials repeatedly stressed that most people in the CHT lacked the political consciousness to perceive the impact of the change. They opposed any referendum because they believed the Chiefs and Headmen of the community would control the wishes of the people. In their proposal to exclude the CHT from the category of tribal area, the policymakers' understanding of the Adivasis reflected the West's perception of the East as 'Other,' as Edward W. Said argued in his influential book Orientalism. A confidential report on the "Proposal for exclusion of the CHT from the category of tribal area" provides insight into the state policymakers' mindset:

"Although considerable enlightenment is slowly creeping into tribal life, the bulk of the population continues passionately to adhere to old tribal laws, customs, and traditions, handed down from generation to generation, which even today largely regulate their pattern of living. An overwhelming majority still live in a world of their own and have little in common with the people inhabiting the rest of the country. They have peers across the border with whom they have far greater ethnical affinity, and even though the lure from outside is greater, they have mostly stuck to their old homes because their old way of life has not been disturbed. The tribals are yet incapable of comprehending political or other fundamental rights. Nonetheless, they enjoy, in quite a large measure, all the fundamental rights exercisable by persons elsewhere in the country."

The Karnaphuli hydroelectric dam at Kaptai significantly impacted the biodiversity and environment. Due to the dam's construction, much wildlife was submerged, and their habitats were destroyed. Indirectly, the dam inundated a large area, putting pressure on the wildlife habitats in other parts of the CHT, as the displaced population from the Kaptai region was forced to clear forests in different areas, thereby shrinking wildlife habitats throughout the CHT.

Conclusion

Frantz Fanon, an Afro-Caribbean French psychiatrist, revolutionary thinker, and philosopher, prophetically apprehended the tribulations of the once-colonised and underdeveloped countries. Fanon writes: "The cracks in it explain how easy it is for young independent countries to switch back from nation to ethnic group and from state to tribe—a regression which is terribly detrimental and prejudicial to the development of the nation and national unity... As we have seen, its [national bourgeoisie of once-colonised underdeveloped countries] vocation is not to transform the nation but prosaically to serve as a conveyor belt for capitalism, forced to camouflage itself behind the mask of neocolonialism." The nature of capitalism in Africa or other colonised regions in the world differed from capitalism in the Western world. It is more appropriate to say that the Black, non-Western, and Indigenous experience of capitalism differs from that of Western people. Recently, some scholars term this form of capitalism, brought by the colonialists, as 'colonial racial capitalism.' They argue that this nature of capitalism persists today. Throughout the British colonial intervention and in the postcolonial states of Pakistan and Bangladesh, the states persistently continued the colonial and neocolonial exploitation of the Adivasis of the CHT through so-called development projects.

All the primary sources used here are from the National Archives of Bangladesh. I am grateful to the staff of the National Archives, particularly Elias Miah, for their generous support.

Azizul Rasel is a faculty member at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (on leave) and a PhD candidate at McGill University, Canada.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments