Reclaiming Panthokunjo from spectral wastelands

We live within ecosystems, engaging in mutual interactions. Ecosystems such as rivers, forests, and agricultural lands are shared resources. In cities, ecosystem services provide essential resources, regulate natural processes, and offer recreational and cultural benefits, enhancing overall quality of life. They are crucial for urban resilience, climate change adaptation and mitigation, and sustainable development.

Today, cities increasingly recognise the life-sustaining role of ecosystem services in ensuring the well-being of both humans and non-humans. People's access to these services is integral to their right to the city. However, cities in the Global South struggle to protect ecosystem services with care, often neglecting them instead of ensuring equitable access and distributional justice.

The concept of wasteland implies that land becomes productive only when it is occupied and improved. Lord Cornwallis's classification of one-third of Bengal's land as wasteland reinforced the East India Company's objective.

Access to ecosystem services aligns with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 10 and 11, which focus on reducing inequality and achieving sustainable cities and communities. While most cities strive toward these goals, Dhaka stumbles, prioritising infrastructure development for private interests at the expense of ecological sustainability.

Citizens have recently expressed concerns about the impact of the Dhaka Elevated Expressway (DEE) project, implemented by the Bangladesh Bridge Authority (BBA), on local ecosystems. The mega infrastructure project involves tree cutting in Panthokunjo, a 5.39-acre urban green space, and landfilling in the adjacent Hatirjheel water catchment area to construct approach ramps at the Moghbazaar intersection. The DEE is a 19.73 km public-private partnership project connecting Kaola, near Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport, to Kutubkhali on the Dhaka-Chattogram Highway. It also includes an additional 27 km of entry and exit ramps at 31 points. Concerns have been raised over multiple deviations at the Moghbazaar intersection, which defy conventional planning principles. These include the investor's late inclusion of approach ramps, the approval of a 3.4 km elevated link to Palashi—expected to generate 18% of total revenue—without feasibility studies, and the suppression of ecological losses in the Environmental Impact Assessment. The project's encroachment on an urban green space and water catchment area raises legal and environmental concerns.

We locate the DEE deviations in the following phases of its chequered evolution: First, BBA pre-qualified investors in November 2009 by carrying out their respective feasibility studies. Second, BBA-appointed consultants prepared alternative route alignments of DEE in August 2010; among the five proposed alternative routes, Routes 1, 3 and 4 were located in greenfield outside Dhaka's Eastern fringe, while Routes 2 and 5 were in the city. Route 3 was the suggested feasible option because of its compatibility with the Strategic Transport Plan 2005, although Route 5 matches the implementing route. Third, an Italian-Thai investor with two Chinese co-investors signed a contract in January 2011 to construct DEE for US$ 1.13 Billion (BDT 4917.57 crore) for completion during 2011-2014 with 27 per cent of the estimated project costs shared by Bangladesh; a revised alignment, overlapping Route 5, was approved in October 2013. Fourth, BBA initiated a parallel "Support to Dhaka Elevated Expressway PPP Project" for land acquisition, rehabilitation of the affected people and transfer of utilities in October 2011 for BDT 4917.57 crore; this raises the public share to BDT 7330.57 crore or 52.9 per cent of the total BDT 13,857 crore public-private investments. Fifth, local consultants prepared an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for BBA in November 2014. Sixth, legal contestation among overseas investors over ownership of shares further deferred the deadline to 2025.

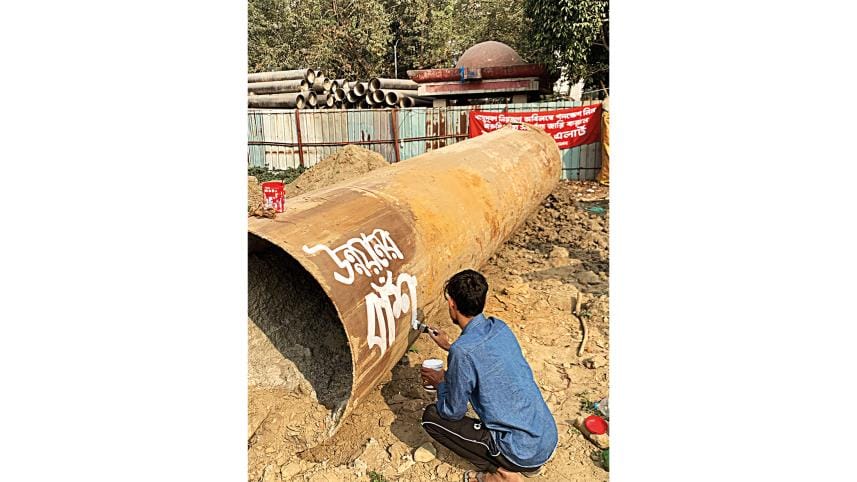

The urgency of the Save Trees Movement, a citizens' rights protection platform with support from the local community, is palpable as they protest the DEE's disruption of local ecosystem services. Their actions, a testament to human resilience, are a response to the exacerbation of the suffering of people in an already least liveable city in the world. More than two months of on-site camping in Panthokunjo have garnered increasing support and built alliances, yet the authorities have not responded. Protests for reclaiming Panthokunjo show an institutional failure to respond and restore the disrupted ecosystem services, underscoring the need for immediate action.

Citizens' movements to resist and reclaim ecosystem services have been evident in Bangladesh since the 1990s, albeit with mixed results; for example, Osmani Udyan in Dhaka was saved from being chosen as the site for the NAM building in 1998, while resistance in 2017 could not stop the construction of the Rampal coal power plant in the Sundarbans, Khulna. It is time to question why citizen movements advocating for the protection of ecosystem services have failed to translate into concrete policies that put an end to the government's and its development partners' alienating practices. Why have mega development projects in ecosystem service provisioning khas lands kept recurring for an alleged best return by violating prevailing laws and public well-being? While failures outweigh the few successes of citizen movements, are we witnessing the colonial past casting a post-colonial trope in disrupting urban ecosystem services? Regarding DEE's disruption over access to urban ecosystems in Dhaka, we argue that the colonial consideration of wastelands for revenue generation has created a post-colonial hegemony in determining present land-use choices, prioritising accumulation over common use for public well-being. Let us examine the possible historical entanglements of the present disrupted ecosystem problem.

Western physiocratic thought on the primacy of land's produce and Western universal liberalism regarding private property were instrumental in the establishment of colonialism in Bengal. In particular, John Locke's labour theory of property guided revenue extraction from land while legitimising colonialism in Bengal. The land remaining idle anywhere in the world, Locke argued, legitimised colonisation for getting the best return from the land. Labour adds value to land for the best return only when people hold land as private property. The East India Company (EIC) directors had their philosophical underpinning in getting the best return from land by the labour theory of property. The EIC implemented colonisation as a scheme for ruling native people in Bengal, arguing that the productive capacity of land in yielding produce would, in turn, generate trade and commerce, leading to the creation of wealth.

The process of turning land into private property in colonial Bengal had never been smooth, considering the nature of disrupting the land-people relation. EIC tapped on the property-constituting power of labour by its translation into the context of Bengal, considering local customs and traditions. The epistemology of this translation led us to probe our present problems around urban ecosystems and their subsequent public acquiring or private illegal grabbing in a longer-term perspective. This epistemological enterprise in historiography is provisional and explores the following questions: How has colonialism differentiated native people in relation to their respective ecological contexts, and how has the colonial legacy continued in disrupting the ecosystem during the post-colonial period, especially under neo-liberalism in Bangladesh since the 1990s? By understanding this historical context, we can better comprehend the present challenges and work towards effective solutions, informing us about the roots of our present challenges.

It is time to question why citizen movements advocating for the protection of ecosystem services have failed to translate into concrete policies that put an end to the government's and its development partners' alienating practices.

Scholars in environmental history claim that no long equilibrium of the ecological regime had ever existed in South Asia, let alone in the Bengal Delta (Rangarajan, 1996). Since ancient periods, unfolding changes explain the transformation of nature into human habitation through a 'common-enclosure dialectic', especially in the Bengal Delta. The concept of commons as shared resources—grazing land, forests, water bodies—and enclosure as an intended parcelling of commons by denying free access are rooted in feudal England; however, their manifestations in south Asia, in ancient periods, are noted in the writings of Kautilya and others. Commons and enclosure are dialectical, as changes in one cause changes in the other; hence, they are discussed as both/and instead of either/or. How this dialectic unfolded in Bengal by appropriating ecosystem services and extending human habitation helps us trace its concomitant impacts on people's lives and livelihoods.

The common-enclosure dialectic in the pre-colonial Bengal Delta was predicated on land clearance; the reclamation of land through forest clearing provided the sovereign ruler with an increasing revenue base while entitling the subjects to the right to cultivation. This dialectic was linked to the spread of religion and the establishment of villages around religious edifices such as temples and mosques in the Bengal Delta. However, the continued nature of this dialectic was radically altered during the colonial period with the emergence of the landed gentry as revenue farmers with their proprietary right to collect revenue from land and the consequent pauperization of the peasantry despite their right to cultivation. How colonial rulers ascribe value to the land is central to the disruption of the common-enclosure dialectic.

The EIC started colonial rule in South Asia by acquiring Dewani of Bengal in 1765. The concept of wasteland has been integral to EIC's progressive imposition of the rule for private property in South Asia, which was implemented by the rule of law. EIC did not use the concept of wasteland in Bengal as a natural category to identify infertile or barren land; it was instead a social category that referred both to unproductive uses of land and to lands held in commons, featuring idle native mentality of not striving for greater productivity of land (Gidwani, 1992). The concept of wasteland implies that land becomes productive only when it is occupied and improved. Lord Cornwallis's classification of one-third of Bengal's land as wasteland reinforced the East India Company's objective. The Permanent Settlement Act of 1793 was the most important land law, aiming to ensure the right of property on land. Its intentions were twofold: to ensure a steady flow of revenue to the EIC coffers and to secure the permanence of the EIC dominion through property. The rule of property and its implementing land laws constituted the basic principles of colonial governance (Guha, 1963).

By adding value to individually enclosed land reclaimed from commons, cultivation initiates the move from a 'state of nature' to a 'state of civilisation,' albeit as a step towards enlightenment (Whitehead, 2012). A state of nature refers to people subsisting as hunter-gatherers on commons without settled agriculture. In contrast, a state of civilisation is equated with acquiring the right to private property in individually enclosed land. Colonial schemes in Bengal, south Asia in general, did not intend the former's progressive dissolution in the latter; scholars of environmental history have noted their retaining instead through a set of binaries. For example, tribes lived in forests in a state of nature, whereas castes lived in fields in a state of civilisation. Castes were seen as productive because they added value to land, generated revenue, and could reclaim wastelands to attain civilisation. Tribes, on the other hand, were judged unproductive for their dependence on the forest commons in a state of nature without private ownership of land. The status of the commons as wastelands was embedded in the colonial construction of a set of exclusionary, if not racial, binaries such as forests-fields, tribes-castes, plains-hills, wastelands-settled cultivation.

Wasteland, in the colonial grand narrative, was a physical category of unmeasured and uncultivated land imbued with social representation of an idle native society in colonial Bengal; this deeply entrenched representation has led to post-colonial (re)categorisation of khas land as state-owned unproductive land of ecosystem services. Spectres of wasteland loom large over post-colonial khas land of ecosystem services, representing unproductive, unauthorised and temporary uses by the marginal people in rural and urban areas just as in plains and hills. Denying rightful claims by landless and marginal people, the post-colonial authoritarian state sanctions the public and private sectors' appropriation of khas land, often in collaboration with overseas lenders and investors, in pursuit of growth-driven development. This sanctioning by the state is part of the neo-liberal development doctrine that normalises khas land grabbing of ecosystem services by the elite and the powerful for 'accumulation by dispossession,' treating it as a zone of exception. Like the EIC Board of Directors, an unholy nexus of politicians, bureaucrats, and technical experts present themselves as the custodians of this neo-liberal development narrative, often justified by a compromised stakeholders' consultation.

The colonial discourse of wasteland produced a form of knowledge—political economy—for governing its subjects that did not decline after its abolition in 1947. On the contrary, it gained a new lease of life; the rule of property around a public-private binary has constituted the spaces of citizenship in post-colonial democracy. Extension of private property and appropriation of khas land continued under the modernisation theory during the 1960s-70s in pursuit of nation-building and intensified through neo-liberal doctrine since the 1990s. Neo-liberal development doctrine views Dhaka ecosystem services—public spaces, peripheral agricultural land, green and blue networks, etc.—as stock spaces waiting for new enclosures in the name of development. The neo-liberal doctrine thus maintains the status quo—ecosystems, whether in khas land or urban spaces, await value addition by and for capital accumulation through either dispossession or exclusion—originating from the colonial translation of Western liberalism through the universal idea of property in Bengal.

Neo-liberal urbanism has made its irreversible mark in Dhaka, with foreign investments and lending in mega urban infrastructure projects aiming to get maximum returns. We acknowledge that these investments have started benefiting mobility patterns within Dhaka for all except marginalised people. Discrepancies in the agreement, however, raise questions about whose interests the positive impacts serve. In DEE, the Chinese investors will collect tolls for twenty-five years for their 47.1 per cent share of investment, contributing only a meagre BDT 272 crore to the public coffers! As the country of origin of global investors is increasingly tangled with regional geopolitics, should citizens passively accept what they are given and endorse a non-responsive state while refraining from voicing concerns over access to ecosystem services? Certainly not. Civic non-response at the cost of urban liveability cannot be an option in a functioning democracy.

We expect our esteemed experts to act as our first line of defence. Citizen dissent should not be left to young activists sleeping rough in tents during long, cold winter nights for months, while experts maintain a conspicuous silence and benefit from the spoils of investments. Last but not least, the DEE debacle is a reminder that no regime can implement its 'production of space' without local expertise. We hope this knowledge does not go to waste.

Shayer Ghafur is a Professor at the Department of Architecture, BUET, where he teaches Southern Urbanism.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments