The making of folk poet Jasimuddin

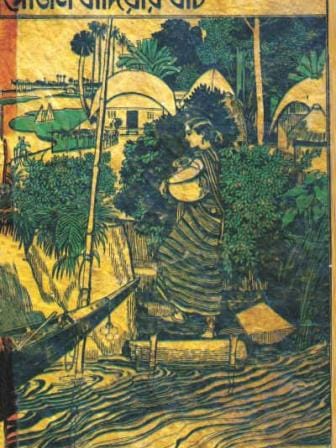

In the year 1903, Jasimuddin was born in Faridpur. It was the month of January. He was born in Tambalpur, his maternal grandfather's home, which was twelve miles away from the city. His natal home was named Gobindopur, just two miles away from Faridpur.

Jasimuddin has written about his childhood. Everything seems so obscure, he wrote. Certainly, he remembered singing songs to himself. He could not remember the words but remembered putting his own words into some of them. He sang that way for hours. He had no listeners, save one. While everyone thought of him as a crazy child, there was one relative, a blind man, whom he called Dadajaan.

Dadajaan was not blind from birth. He had some eye ailment and his parents sought the help of local quacks. They suggested applying chilli paste to the eyes. Simple as they were, they actually did that, and the eyes became blind. Dadajaan had no formal schooling. He lived in the same household as Jasimuddin. He narrated many stories, poems, mores, and myths. He listened to Jasimuddin when he sang to himself.

Jasimuddin accompanied Dadajaan, carrying his stick with him wherever he went. There were so many welcoming homes. Wherever he went, Dadajaan sat down and, like Pandora's box, a whole array of poems, stories, and narratives started pouring in. Jasimuddin listened attentively as people shared their stories with his close relative, alias Dadajaan.

During night-time, Dadajaan would narrate interesting stories in their yard. The womenfolk in the household, i.e. mothers and aunts, sat on the other side and listened in admiration. People from nearby villages came to listen to him; they were given a different area to sit in. He was positioned in such a way that both the outsiders and the ladies of the family could be an audience. As he narrated the stories, he also inserted some songs. Jasimuddin and his brothers and cousins joined in the singing—ballads like Mohua Sundori, Rupbaan, Abdul Badsah, Tajul Mulk, Kou Kou Pakhi, and many more. As he listened to these stories, young Jasimuddin would fall asleep, and his dreams were invaded by those kings and queens, princes and princesses.

He went to a kindergarten school and memorised many poems. Some of them remained with him for life. When he wrote about his childhood, he could still recite some of them. They were associated with wonderful memories from childhood, and the rhythm of those poems also left a permanent impact. Jasimuddin thought that all poems were just there, like the sun, moon, and stars. He never thought that someone actually wrote them. His brother found an old copy which belonged to his father. The brother read out a poem from that copy. This was the first time that Jasimuddin learned about a poet. So people write poems, he thought—wow. His father was a poet!

Jasimuddin's father was a schoolteacher. He had very humble means and spent them on the education of Jasimuddin and his brothers. Jasimuddin's mother was very simple. She missed her natal home, and whenever she had an idle moment she talked about the times spent there. She had a very nice manner of speech. Jasimuddin writes that he never again met anyone who had such a lovely manner of speech. She talked mostly about sad, melancholic stories. Jasimuddin became teary-eyed when he listened to them. Later, in his book Dhan khet, he included some of the themes which were originally narrated to him by his mother.

The village next to theirs was called Shobharampur, and Ambika Master had a pathshala in the house of the Chowdhurys. Jasimuddin studied there, and he was later admitted to a school in Faridpur. His father, Moulvi Ansaruddin Ahmed, was a teacher in this school. Here he met Monoranjan Bhattacharya, the son of the famous historian Bisheswar Bhattacharya. Monoranjan and Jasimuddin spent a lot of time together. They read books together and discussed their possible pathways to becoming famous poets and litterateurs. Monoranjan also became a famous author; his publications include works for children as well.

When Jasimuddin was in class four, he met a team of saints. They were visiting a neighbouring area, and Jasimuddin was deeply impressed by them. Many people visited the saints and brought fruits and other delicacies for them. In turn, the saints showed affection towards Jasimuddin, and he always received a share of the offerings. When they described their feats of visiting the Umanand Mountains, the Vindhyachal Mountains, and Kedar Badrinath, Jasimuddin was completely taken by their stories. He decided to become a saint when he grew up. He stopped taking onion and garlic with his food. His mother cooked for the family herself, and in their humble abode she could not prepare separate meals for Jasimuddin alone. To keep his vow intact, Jasimuddin often went without food. He walked barefoot, and even when the sun displayed its scorching self, he remained without footwear.

When the saints left for another destination, eight-year-old Jasimuddin was devastated. For two days and two nights, he stayed near the riverbanks, hoping the saints would return. He fell behind in his studies. His friend Dhirendranath Bandopadhyay's mother strongly encouraged him to return to his studies.

In class seven, their house was engulfed by the river. They took refuge in the home of another relative in Alipur. Jasimuddin often visited Dhiren there and was allowed to study in that household. He wrote some poems in his journal, and Dhiren's sister, Pokojini, showed them to their father. He was otherwise stern and reserved, but he read the poems and expressed great affection for Jasimuddin. In this home, Jasimuddin read many books and gained knowledge about Hindu deities.

Another professor of logic from Faridpur Rajendra College had a significant influence on the poet. His name was A. C. Sen, and he explained various distinctions within Hinduism and the Brahma Samaj. Jasimuddin later read an essay on rural England and was inspired to write about village life in Bengal.

In class nine, he ran away to Kolkata. He later wrote about this experience in his article titled Nazrul Islam. With great difficulty, he managed to reach Kazi Nazrul Islam in Kolkata. Nazrul asked him to leave his manuscript behind and return at four pm. Nazrul was surrounded by other people, and Jasimuddin did not get a chance to speak to him properly. However, he was able to listen to Nazrul Islam's recitation of the poem Polatok. That sonorous voice stayed with him forever.

Jasimuddin formed a bond with Kazi Nazrul Islam. He returned to his village and tried to resume his studies. He often sent some of his poems to Nazrul Islam, who had them published in various places. His first poem was published in Probashi magazine when he was in class nine.

Jasimuddin completed his matriculation examinations. There was a village on the other side of the river. From his own village, he had to cross the river to reach it. He often went there and heard village boys expressing themselves through songs and poems. He loved the rural people and established a school there. He frequently went without food to reach the village on time and teach the boys and girls. He wrote that he loved this village more than his own and yearned to share its literature with the outside world. He used to plough the land with local agricultural workers, and through this labour he learned more and more.

He served as a part-time volunteer for the Congress party, which took him to Kolkata once again. He aspired to meet poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, but this proved difficult. However, he coincidentally met Dr Md Shahidullah, who was on his way to visit poet Dinesh Babu. Jasimuddin shared his notebook of poems with Dinesh Babu. Dinesh Babu immediately wrote to Dr Sen, requesting him to find a position for Jasimuddin as a poem collector from the villages. Jasimuddin shared his poems, and Dinesh Babu told him that he had been waiting for such an opportune moment. He secured Jasimuddin a position as a folk collector and remarked that while there would be many poets, Jasimuddin would be the one to become a folk collector. Thus began his journey as a folk poet.

Nashid Kamal is an Adjunct Professor at BRAC University, a Nazrul exponent, and a translator.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.