Kamruddin Ahmad: A visionary political thinker we must remember

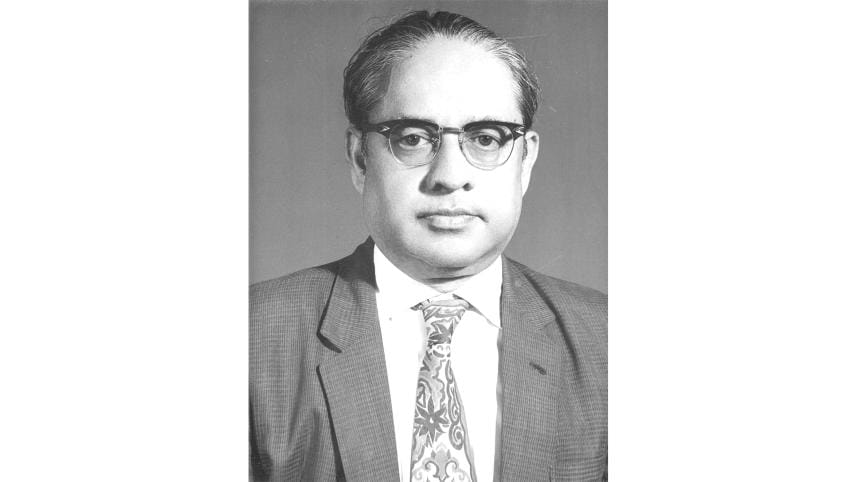

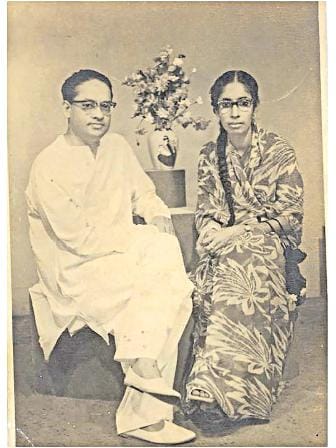

In a quiet neighbourhood of a once lush green residential area of Dhanmondi, I grew up in a three-storied house that dates back to the year 1957, listening wide-eyed to stories of a man deeply involved in Bangladesh's struggle for sovereignty and democracy. It is hard to come up with a title that befits Kamruddin Ahmad. Having played different roles throughout his lifetime—politician, historian, writer, diplomat, language activist, or trade unionist—he crafted himself into whatever the country needed him to be at that point in time, in the quest for liberty. Yet, despite his vast contributions, his name is seldom mentioned in mainstream discussions of Bangladesh's political history. At a time when Bangladesh is at a crossroads—grappling with the remnants of authoritarianism while striving for meaningful reforms and principled leadership—his vision and unwavering commitment to democracy, the rule of law, and historical documentation offer lessons that remain strikingly relevant today.

Born on September 8, 1912, in Sholaghar village in Munshiganj District, Kamruddin Ahmad demonstrated early academic brilliance and intellectual curiosity. He studied at Barisal Zilla School and B.M. College. His initial hostel days were carefree and full of youthful exuberance, but they quickly turned somber after he lost his doting mother in 1929, severing all ties with his family. He moved to the capital to stay with a paternal uncle while earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1934 and a Master of Arts in English in 1935 from the University of Dhaka, later pursuing law in the 1940s from the same institution.

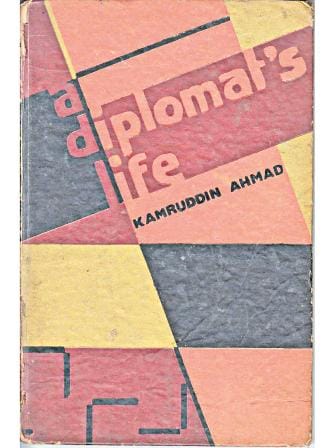

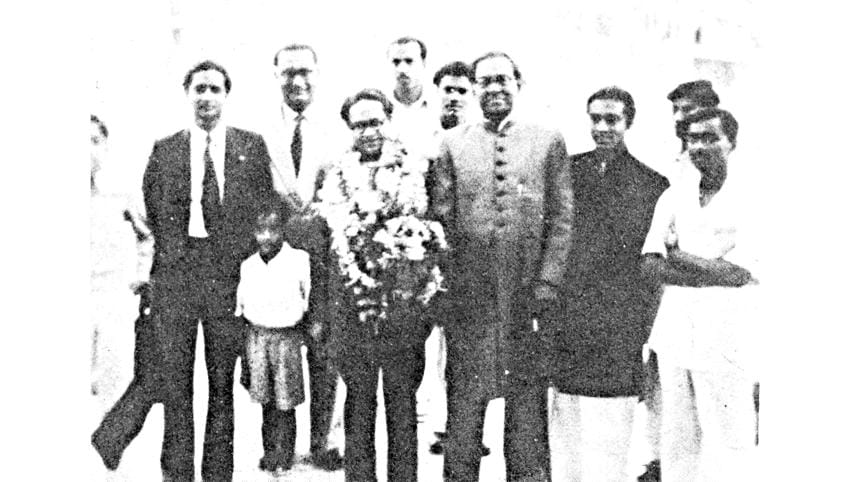

Ahmad began his career as a teacher at Armanitola Government High School in Dhaka but soon found his calling in politics. Initially, he was aligned with the Muslim League, supporting its political vision, but after the partition of 1947, he shifted his allegiance to the Awami League, believing it better represented the aspirations of Bengalis. However, disillusioned with party politics, he left and joined the diplomatic service. He served as Pakistan's Deputy High Commissioner in Kolkata and later as Ambassador to Myanmar and Cambodia before retiring from diplomacy. By 1962, he had turned to legal practice while also remaining active as a trade unionist. His involvement in politics was never a matter of personal ambition but rather a reflection of his dedication to justice and social reform.

"Party politics has never attracted me. I have never applied to any party for council membership in my life. I didn't even go to the polling station to cast my vote. As long as I have been associated with politics, I have done the politics of the country, but I was not a member of any party except for two years from 1955. I believe in the politics of men, but not party politics. I have never been tempted by power. I remain a student of politics forever, but I never became a political leader."

He was a vital figure in the Sarba-daliya Rastrabhasa Sangram Parishad, advocating for Bengali to be recognised as a state language. His efforts contributed to the foundations of the Language Movement, a pivotal moment in Bangladesh's history. According to Rash B Ghosh, an Indian politician, "Various progressive political forces of East Bengal started mobilising support for making Bengali one of the state languages of Pakistan even before the emergence of the nation. For instance, some of the Bengali Muslim Leaguers formed the Gono Azadi League under the leadership of Kamruddin Ahmad in July 1947. In its manifesto, [he] clearly emphasised: 'Bangla will be our state language. All necessary steps need to be taken immediately for making Bangla language suitable for all parts of Pakistan. Bangla shall be the only official language of East Pakistan.'"

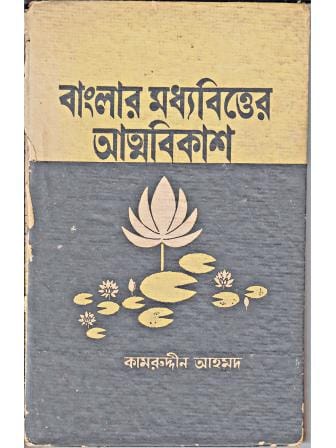

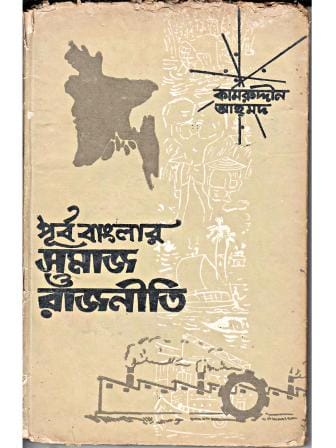

Apart from being a statesman, Ahmad was a prolific writer and historian. His books offer critical insights into Bengal's socio-political developments and the ideological underpinnings of Bangladesh's independence. He meticulously documented the struggles of the people, the failures of political leadership, and the lessons that should be drawn from history. His writings serve as essential readings for anyone seeking to understand the history of Bangladesh beyond conventional narratives. Ahmad authored several books, including A Social History of Bengal (1957), A Socio-Political History of Bengal, The Birth of Bangladesh, Purba Banglar Samaj O Rajneeti (1976), Banglar Madhyabitter Atmabikash (two vols), Swadhin Banglar Abhyuday Ebong Atapar (1982), and Banglar Ek Madhyabitter Atmakahini. His most popular books revolve around the theme of the Muslim middle class, where he observed the development of the Bengali Muslim middle class as a complex process and discussed the dilemmas of this class, their struggles, and their prospects. He writes, "One of the characteristics of the Bengali middle class was that they were divided. On the one hand, they had tradition, and on the other hand, they had the desire to modernise."

"I believe in the politics of men, but not party politics. I have never been tempted by power. I remain a student of politics forever, but I never became a political leader."

Now, more than four decades after his demise, even his magnum opus of books is all but forgotten. Collecting dust on the bookshelves of my own house, despite being his granddaughter, I myself do not find the time to pick them up, despite my mother's incessant requests. Only a handful of researchers, academicians, or intellectuals know about him or the extent to which this man has contributed to the sociopolitical fabric of this nation. One can only assume how unaware most of the younger generation is about him, which is dismal, given the state of affairs in the country and how impactful his philosophies and historically objective documentation of the political landscape could have been for those invested in the future of the country.

It is quite interesting that he removed himself from politics early on, having lost interest or not wanting to compromise his principles, yet he chose to be an avid observer and commentator. In the words of Professor Salimullah Khan, published in this daily a decade back, "Kamruddin Ahmad is a witness, a man of great introspection. He is a historian who writes in full spotlight of the other's gaze. 'A man who was himself involved in the political turmoil for more than a quarter of a century,' he admits, 'cannot pretend to be aloof.' He nevertheless betroths objectivity of sorts: 'I have, however, tried to be as objective as possible because I am conscious that I might become a source for future historians.' It's not too much to say that he partly succeeded."

The man dedicated his life to the betterment of this country not only professionally but also personally, making the ultimate sacrifice of losing his youngest son, Nizamuddin Azad, who fought in the Liberation War of 1971 as a member of the Mukti Bahini. The rebellious son, a student activist involved in a Communist Party group, was named after freedom itself—it was as if Kamruddin Ahmad had finally met his match in the family, and their fate was intertwined, with the father outliving his son.

In May 1971, Azad left home to join the guerrilla forces fighting for Bangladesh's liberation. In October 1971, the Pakistan Army arrested Kamruddin Ahmad, who faced the same brutality inflicted upon many intellectuals and political figures of the time. His arrest was a reflection of the broader crackdown on those who resisted Pakistan's rule. He remained in jail until Bangladesh's victory, and on December 17, 1971, the morning after the Pakistani Armed Forces surrendered, he was finally released. However, upon his release, he learned that Azad had never returned from the war. This devastating news marked a turning point in his life, and those who knew him say he was never quite the same again.

Kamruddin Ahmad remained a significant figure in politics and academia post-independence. As General Secretary of the Trade Union Federation, he tirelessly worked for labour rights and social justice. His tenure as President of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (1976–1978) allowed him to document and preserve Bangladesh's political and historical heritage. More than a politician, he was an intellectual force, a historian, and a mentor Bangladesh never fully recognized. As the country moves forward, revisiting his teachings and leadership could help build a more informed, progressive, and ethical political landscape.

In this moment of crisis, the country desperately needs leaders like him—those who champion democracy, social justice, and historical awareness. The absence of ethical leadership and intellectual discourse in contemporary politics makes Kamruddin Ahmad's legacy more pivotal than ever. His emphasis on historical awareness, democratic values, and political ethics could have helped provide a roadmap for the nation's future. His vision for Bangladesh was one where education, political consciousness, and justice shaped governance, and his ability to analyse political shifts and advocate for social reform is something today's leaders and young activists can learn from.

His son's sacrifice in the Liberation War stands as a testament to the values he instilled—proving that true patriotism is about service and sacrifice, not just rhetoric. His journey reminds me of the notion that even if you steer far away from politics, you make a political statement. To come across someone who was involved in the political landscape not to seek leadership or power, but to become a tour de force as a witness, thinker, and historian is rare. Perhaps his way of politics is what the country direly needs right now.

Iqra L Qamari is a project development consultant, a writer, and Kamruddin Ahmad's granddaughter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments