A journey through Bangladesh’s Islamic inscriptions

Architectural inscriptions are a fascinating aspect of our cultural heritage because of their rich and diverse historical content and artistic merit. Arabic and Persian inscriptions of Bengal help us understand the advent of Islam in the region, which eventually made Bengali Muslims the second-largest linguistic group in the Islamic world.

That the science of epigraphy in the world of Islam started at the hands of Jamaluddin Shībī, an early fifteenth-century academic and scholar at the famous Bengali Seminary in Makkah, is one among many remarkable historical revelations in the field. His study illustrated superbly how wonderfully these fascinating inscriptions help us in finding the missing links in the cultural continuity of the old world, which eventually resulted in the "globalisation of the medieval world of Islam".

The tradition of inscribing Arabic and Persian on stone in Bengal started with a Persian inscription of the third Muslim ruler, Sultan 'Alā' Dīn ('Alī Mardān) Khalji, immediately after the conquest of Bengal in the early thirteenth century. This, as well as another superb Persian inscription of another early Khalji ruler of Bengal — Balkā Khān Khaljī (626–628 A.H./1229–1230 C.E.) — indicates that the Persian language was patronised by the ruling Muslim elite from the very beginning.

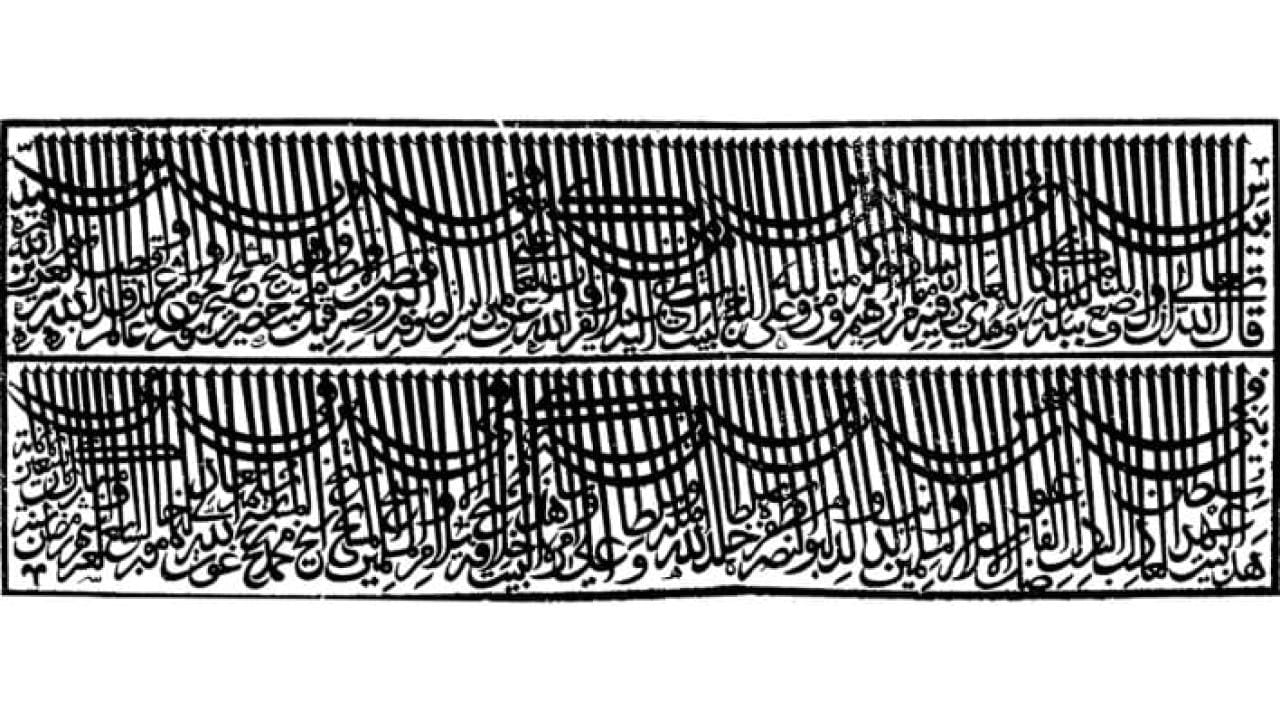

The fabulous Arabic inscription of Nīm Darwāza, which I (the author) discovered in a mosque in Mahdipur village in the vicinity of the medieval Bengal capital Gaur, is one of the most exquisite inscriptions in the world. This inscription, as well as the Chānd Darwaza Arabic inscription, once decorated two monumental entrances of the sultanate palace in Gaur. Unfortunately, during the colonial period, European antique collectors transferred many inscriptions to their homelands.

Colonel Franklin, to cite one example, moved quite a few Arabic inscriptions — including the Chānd Darwaza inscription — from Bengal to his country home in England.

Inscriptions serve as a missing link to the past, offering many historical clues otherwise unavailable elsewhere. Arabic and Persian inscriptions form a significant element of Islamic architectural decoration due to their aesthetic appeal. They are rich in textual content, artistic manifestation, and diversity of form. They shed fresh light on the cultural dynamics of a crucial period of history and help us understand the complex religious transformation process in the region. These epigraphic evidences suggest religious harmony, cultural continuity, and mutual understanding among peoples of various identities in Sultanate Bengal.

Titles in Islamic inscriptions portray the worldly ambition for power and glory of the ruling class, albeit over-toned with religious fervour, often turning into what might today be termed "politically correct" or "euphemistic expressions". The high standards displayed in the literary style of these epigraphic texts, their aesthetic exuberance, and their calligraphic refinement remind us of cultural continuity across different regions — a phenomenon that may be described as the "globalisation of the old world".

Interreligious relations are an important lens through which to understand the history and culture of the Bengal Sultanate. One reason Muslim dynasties lasted for such a long time, compared with many earlier dynasties such as the Pala and the Sena, was that Muslim rulers, in general, adopted a moderate approach to interreligious relations. Indeed, they were far more tolerant than they are usually given credit for. None of the inscriptions record any wilful destruction of religious buildings or temples during the Sultanate or Mughal periods.

The tradition of interfaith marriages, for instance, existed, as indicated in the Ghaibi Dighi Arabic inscription. It records that Lakshmi, a Hindu woman and the mother of Khān Jahān Rahmat Khān, built a mosque in Sylhet in 868 A.H./1464 C.E. These epigraphic evidences indicate religious harmony, cultural continuity, and mutual understanding among peoples of various identities in that period.

Epigraphic evidence suggests that Islam gradually assimilated into Bengali life harmoniously and became part of the land's natural experience — more as a new civilisation that refreshed the region with cultural dynamism than as merely a set of ritualistic tenets. Islam thus emerged as a social system well suited to the common people of rural Bengal. It rapidly became a popular way of life in the ever-growing Bengali villages, as human settlement expanded along the delta, alongside the spread of rice cultivation and the clearing of forested marshland.

Bengal's remarkable ecological balance and natural harmony are represented in a number of inscriptions, albeit in abstract forms, as reflected in the Babargram inscription (dated 905 A.H./1500 C.E.). Bengali Islam was accommodating enough to welcome semi-Hinduised tribes, nomads, and various other local groups into a new civilisational sphere, to the extent that non-Muslims were free to visit mosques — as depicted in the earliest Arabic manuscript of Bengal, Ḥawḍ al-Ḥayāt — as well as khānqāhs and madrasas.

In an era when the communication revolution is gradually turning the earth into a global village, it is very important for us to understand the diverse and complex world of Islam, which represents more than one-fifth (nearly 23%) of the human population. A tremendous transformation is taking place almost everywhere in the lives, societies, and political systems of these vast populations. These rapid changes are especially visible in the eastern parts of South Asia.

The fabulous Arabic inscription of Nīm Darwāza, which I (the author) discovered in a mosque in Mahdipur village in the vicinity of the medieval Bengal capital Gaur, is one of the most exquisite inscriptions in the world. This inscription, as well as the Chānd Darwaza Arabic inscription, once decorated two monumental entrances of the sultanate palace in Gaur.

The resurgence of Islamic norms and values among Muslims makes it even more important that we understand the history, religion, and culture of the Islamic world in their proper context and in greater depth. Fortunately, the inscriptions of Bengal have much to offer in helping us understand historical Islam.

A well-known French colonial administrator in North Africa once compared the world of Islam to a resonant box: the faintest sound in one corner reverberates throughout the whole. As elsewhere in the Islamic world, this apt metaphor also finds expression in Bengal, a significant part of which constitutes present-day Bangladesh, the third most populous Muslim country in the world. Thus, despite their many distinctive local cultural features, one soon discovers in these remarkable epigraphic treasures a vibrant message — unity within diversity — that is deeply rooted in the pluralistic Bengali culture of this eastern region of South Asia, as much as in the broader Islamic culture in both historical and global contexts.

Prof Dr Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq is a renowned expert in Islamic history and epigraphy. He can be contacted at siddiq.mohammad@gmail.com.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments