Jamdani as the battleground

The Dangers of "Shared History"

Against my better judgment, I found myself in a rather heated online debate with Indian Bengalis regarding a video made by a popular Indian influencer on the issue of Jamdani. Ishita Mangal, in her series on regional Indian outfits, highlighted the Jamdani saree as a symbol of pride for West Bengal, noting how the British attempted to destroy or erase it but ultimately failed.

There are several things happening in the short clip: a quick photo of a Bangladeshi Jamdani, a reference to Charulata, and then her own Rabindric styling of what she presents as a Jamdani but is, in fact, a Dhakai Jamdani. In trying to explain the mistakes in the video—and that the Jamdani is not an Indian product but a Bangladeshi one—I was bombarded with a barrage of unsubstantiated claims and comments, all under the guise of "shared history." Indian sentimentality had been hurt.

I usually enjoy Mangal's content, which blends good humour with well-researched fashion and styling insights. And yet, just like a Sanjay Leela Bhansali film about Bengalis that prioritises grandeur over depth, Mangal made a rather khichuri—a debacle—out of Jamdani classification in a 30-second reel.

More so, the online comments—often ill-informed yet brimming with confidence—fall squarely within the current trend of Indian insistence on their dominance over all things Bangladesh. What is more interesting is the construction of the "shared history" narrative by a certain section of Indians who consider themselves critical of their right-wing government and yet live and function quite comfortably within that regime.

The "shared history" narrative operates under the guise of liberalism, aiming to diffuse any form of tension and co-opt Bangladeshis into accepting Indian narratives. Yet in the face of any critique—let alone criticism—there is immediate defensiveness and often racialised remarks against Bangladeshis.

The lack of critical self-reflection and awareness while positioning oneself as "liberal", in my view, is far more dangerous and detrimental than bigots who are open about their hatred. At least with the latter, there is no pretence.

But before I delve into the problem with "shared history", let me revisit Mangal's video and some basic history of the Jamdani to set the stage.

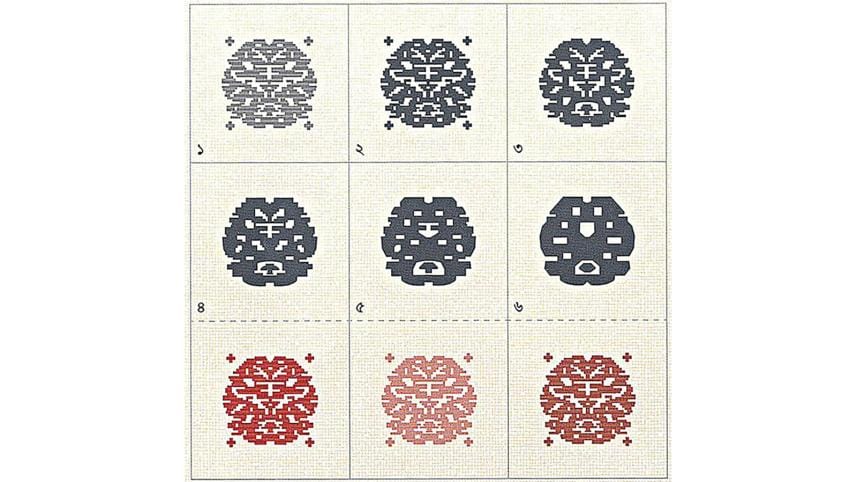

In the video, Mangal is wearing what is known as the Dhakai Jamdani, a West Bengali cotton saree with motifs embroidered on the jomin (body) and anchol (end). These sarees have geometric patterns similar to those of the original Jamdani, but neither the quality of the fabric nor the designs meet the established criteria of what constitutes a true Jamdani (see CPD & NCCB Report 2014).

That is what Mangal is wearing—a Dhakai Jamdani—which is a misnomer, because why would a West Bengali saree be called Dhakai Jamdani? A simple internet search shows that after the partition of India and Pakistan, many Hindu Bengali tantis (weavers) were forced to migrate to West Bengal, where they formed their own community. It is important to note that Jamdani was the specialisation of Muslim weavers. The weaving community in West Bengal (mainly Hindus) likely created sarees inspired by Bengal's Jamdani tradition. The term Dhakai, therefore, refers more to the origins of the tantis than to the actual fabric or weaving technique.

Additionally, the video features a photo of Madhabi Mukherjee as Tagore's protagonist Charulata, made iconic in Satyajit Ray's film, where she is seen wearing a Bengal Jamdani. During Tagorean times, Jamdani was worn by the elites but was also recognised as a saree from Dhaka, not from Kolkata or its surrounding regions. There's also a quick image of a contemporary Jamdani—one that any Bangladeshi woman might have in her wardrobe. Again, this is not a Dhakai Jamdani but a Bangladeshi Jamdani, wrongly labelled as a West Bengal product.

One may argue—what is the harm in a little mix-up? This is precisely where the danger of the "shared history" framing comes in. Another quick internet search reveals hundreds of Indian websites extensively discussing "Bengal Jamdani," using photos of sarees that are clearly not Bangladeshi Jamdani—or even related to it. Many of these sites also mention that Jamdani is UNESCO GI-protected, but conveniently omit the fact that this recognition belongs to Bangladesh, not India. It is an act of deliberate misinformation by omission. As a result, Jamdani is increasingly portrayed as an Indian fabric and form of craftsmanship.

Little lies have big consequences.

From the Indian side, the "shared history" framing appears frequently—be it in seemingly trivial cricket banter, difficult trade and diplomatic negotiations, or even the dangerous reduction of Bangladesh's War of Independence to the so-called "Indo-Pak War." This framing becomes a convenient tool to water down political tensions while subtly encroaching on anything uniquely Bangladeshi.

In recent years, India has tried to register the GI status of Tangail craftsmanship—a tradition from a Bangladeshi district nowhere near India. Designers like Gaurang Shah have even blatantly lied (and gotten away with it) in interviews, claiming to have "invented" the Jamdani, a weaving tradition that dates back centuries.

This "shared history" narrative offers an easy way out when Indians are caught in an international lie or fact-checked on social media. It is layered with neo-imperialism that manifests as a constant infantilisation of Bangladeshis.

Even in global academic circles, while I've been fortunate to work with phenomenal mentors and students of Indian origin, there remains a significant number of Indian academics—both seniors and juniors—who routinely undermine Bangladeshi colleagues. They attempt to "educate" us in our own areas of expertise.

Some have even committed gross academic dishonesty by ignoring well-documented Jamdani history and presenting it as their own research at world-renowned universities. The "shared history" narrative has been used to play dirty, while expecting us to roll over and take it.

But why this fascination—almost obsession—with the Jamdani?

The simple answer is that the Jamdani is magnificent. According to the seminal book Traditional Jamdani Designs (2018) by the National Crafts Council of Bangladesh (NCCB), the Jamdani, as it is crafted in Bangladesh, is the last remnant of Bengal's muslin weaving tradition, which was systematically destroyed during British colonial rule. It is cotton weaving at its finest.

Unlike other sarees, the motifs are not embroidered or printed, but woven directly on the loom. This craftsmanship is a family affair, passed down orally from generation to generation. In the same book, one of the pioneers of Bangladeshi heritage conservation, the late Ruby Ghuznavi, wrote extensively about the indigeneity of cotton in ancient India, the superior Indian cotton looming techniques that captivated the world through Arab traders, the evolution of muslin, and the perfection that was Bengal/Dhaka muslin during the Mughal era.

Important for this piece is her discussion of the factors that made Dhaka muslin superior to any other of its time:

- Phuti karpas—a specific cotton that grew around the Dhaka region due to the mineral-rich silt deposits of the River Meghna,

- the fineness of its handspun yarn, and

- the delicate yet extraordinary skills of the weavers—initially Brahmin women.

Bit by bit, design motifs—jaam (flower), dani (vase)—inspired by Persian designs, appeared on the muslin yards, becoming what is now known as Jamdani.

"While muslins were woven mainly by Hindu weavers (tantis), Jamdanis were primarily the forte of Muslim weavers (julaha)" (Ghuznavi 2018: 25).

Due to various factors, muslin weavers migrated to other textile centres in what is now West Bengal. Interestingly, Jamdani weavers remained in the greater Dacca region—a reality that holds true to this day.

Jamdani is not just the material or the motifs; it encompasses everything—from the river system and flora-fauna of the Dhaka region, to the pit loom, the weaving technique, the oral directives, the family heritage, and the way of life surrounding this art.

Along with the story of master craftsmanship, the Jamdani is also one of quiet resilience and resistance—surviving British atrocities against Bengal/Mughal muslin, colonial and World War-induced famines, the partition of India and Pakistan, and later, Bangladesh's War of Independence.

The Jamdani, I will argue, is a material expression of Bengal's decolonisation. Its sheer existence is an act of resistance—with the weaving technique serving as the subaltern's way of speaking to power, telling their stories, and expressing the human necessity to create art, even in the face of great adversity.

There was a time when the Jamdani community was dying out. Through extensive resurgence efforts by the Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation (BSCIC) in the 1980s and 1990s—supported by designers, craft specialists, academics, development organisations, and patrons—the Jamdani Village was established in Sonargaon, Bangladesh (Ghuznavi 2018: 33).

On a personal note, growing up in different countries as a child, I was taught by my mother and the Bangladesh Foreign Service aunties the importance of always having at least one Jamdani and one Nakshi Kantha saree in our wardrobes. It was predominantly a women's collective effort to support local craftsmanship and ensure that the younger generation understood the importance of representing our heritage on the world stage. This is a lesson I continue to practise to this day.

But we are a long way from that earlier struggle. Today, the Jamdani industry in Bangladesh is booming—with established handicraft stores such as Aarong, Aranya, Kumudini, and others boasting wide collections, hosting fashion shows and fairs dedicated to Jamdani.

There are innumerable saree stores across the country selling affordable Jamdanis, as well as niche boutiques specialising in high-end, one-of-a-kind pieces.

And yet, despite this thriving Jamdani industry, it continues to be subsumed under the Indian "shared history" narrative.

Moreover, under this insidious framing, global art exhibitions and conservation projects continue to showcase Bangladeshi Jamdani as Indian heritage, almost never acknowledging that the Jamdani is thriving in this part of Bengal.

Last year, I was able to visit The Design Museum of London's SARI/STATEMENT exhibition in Amsterdam twice. And while the exhibition was well-curated, the West Bengal Jamdani on display was perhaps one of the worst I have ever seen.

No self-respecting Bangladeshi woman or tanti would ever own or claim such a poorly woven saree—nor insult Jamdani by calling it such. And yet, it was one of the main pieces in the exhibition, claiming to be the continuity of Bengal's muslin legacy.

Our weak diplomatic efforts, our inability to effectively market Bangladesh and showcase our histories, allow for such blatant misrepresentation to go unchecked. When enough layers of falsity are repeated, even well-documented history can be overturned.

There are those working across the two Bengals to curate and restore our shared heritage. But the exhibitions, research, and technical expertise largely remain on the Indian side of the border—with only a select few Bangladeshis having access to such spaces.

Social media-driven commerce has created immense opportunities for entrepreneurs across the region.

There is no doubt that Indian fashion houses play a significant role in globalising regional craftsmanship. Designers like Sabyasachi, Rahul Mishra, and Anita Dongre have become synonymous with luxury, comparable to global icons like Yves Saint Laurent and Christian Dior.

Indian fashion houses excel in e-commerce, and Bangladeshi counterparts have started adopting similar strategies. To appeal to the Indian market, Bangladeshi Jamdani sellers either directly sell pieces to Indian boutiques—who then rename them as "Dhakai Jamdani"—or, worse, Bangladeshi boutiques themselves have begun calling Jamdanis "Dhakai Jamdani."

While it is both difficult and morally unjustifiable to police individual sellers who are simply trying to keep their businesses afloat, this act of compliance—to make Jamdani more digestible for the Indian market—is a manifestation of Bangladesh's perpetual approval-seeking behaviour from India in all matters: from politics to economics to socio-cultural production.

What's in a name? Jamdani by any other name would not be Jamdani!

Some may argue that perhaps I am too sensitive about what gets called "Jamdani"—because, to quote the famous bard, "What's in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet."

And yet, there is something specifically known as the "English Rose," which is a trademark in and of itself!

Correct naming, recognition, and differentiation of Jamdani matter. It is crucial to ensure that the regal Jamdani is not lost in the misnomer of the "Dhakai Jamdani." Our Jamdani is uniquely a Dhaka story, intricately woven into the region and the city. It is a story of resilience through waves of turmoil, of a community's continuity in the face of change, and of resistance to adversaries—both large and small, foreign and local.

It would be a tragedy if, after surviving all these challenges, the name and history of Jamdani became blurred with "Dhakai Jamdani" for the sake of social media relevance and Indian comfort.

Perhaps now is the time to hold ourselves and our national agenda to higher standards.

A big step towards that would be:

- engaging in critical archival research,

- restoring historical documents and monuments,

- ceasing the demolition of buildings and structures simply because we disagree with their politics, and

- investing in arts and craftsmanship.

And perhaps, this is also a good time to reflect on how much of this regressive "shared history" discourse we are willing to endure in the name of maintaining neighbourly peace.

Maybe we can learn from the Jamdani itself—how it survived immense adversity and still carries its resplendence.

Many of the motifs have changed over time, and yet the cotton yarn, weaving techniques, tutelage, and pit loom have remained enduring markers.

My personal favourite part of the Jamdani's history is that all the original materials are indigenously Dhaka: the cotton that grew in the region, the mineral-rich silt deposited by the Meghna and Shitalakhya rivers, and the boal fish bone that was initially used for weaving.

The topography of Dacca/Dhaka is woven into the Jamdani—nodi, mati, maach.

To lose Jamdani is to lose ourselves.

Shahana Siddiqui is an anthropologist and currently a guest researcher at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. She is a saree—especially Jamdani—enthusiast.

(Special thanks to Maheen Khan, Sheikh Saifur Rahman, and Sharmin Rahman for expert insights. Thank you, Seama Mowri and Muntasir Mamun, for your valuable comments.)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments