An Iconic History of Bengal

In the sixties of the last century, I earned my primary degree with majors in Philosophy and Indian Studies and became a secondary school teacher. The somewhat recently established Indian Studies Department at the University of Melbourne was a very fraternal institution, one with which it was easy to maintain relations even after graduation. The Chairman of the Department was the very reserved Sibnarayan Ray; the Belgian Indologist, Dr. Joseph Jordens, oversaw the classical offerings of the curriculum; and Mr. (soon to be Dr.) Atindra Mojumder, a man of apparently boundless energy and enthusiasm, managed everything else. Atindra-babu told me about a former teacher of his named Dr. Niharranjan Ray and some of his works, including a history of the Bengali people. He suggested that my Bengali was a lot better than I believed and persuaded me to translate Bangalir Itihas or History of the Bengali People and submit it as a footnote to a thesis on its author. After a year, the undertaking was upgraded to a doctoral project, and a few years after that, Bengali Vernacular Historiography: Niharranjan Ray – A Case Study emerged successfully. Almost immediately, the translation was snapped up by Orient Longman; the thesis part took a bit longer to find a publisher (It was published by Sahitya Akademi in Calcutta in its Makers of Indian Literature series).

Bangalir Itihas does, indeed, bring kings, for example, into the scheme of things, though not so much in their own right; rather, royal worthiness is assessed by what kingship might have done for society as a whole, and that obviously includes the common people. So, Ray's History soon came to be known as 'history from the bottom.'

I first met Niharranjan Ray in, I think, 1978. I was staying at the Ramakrishna Mission Guesthouse in Golpark, and from the roundabout in front of the stately building runs Purna Das Road, off the far end of which, near Rashbehari Avenue, ran a lane where the Ray family home stood. So, one Sunday after lunch, I set off with Atindra Mojumder's letter of introduction to meet the great man. I found the house easily and rang the doorbell. I was about to leave after the third ring when the door was opened by an elderly and evidently sleepy man wearing a lungi and a slightly tattered genji. I asked the servant if I might see Dr. Ray, and with a warm smile and a soft voice, the servant replied, "I am Dr. Ray." I had yet to learn of one of the best bad habits of the Bengalis - the after-lunch snooze, especially on a Sunday.

He welcomed me into his living room and, having learned that I had translated nothing of any magnitude before, proceeded to offer me some advice, the essence of which was not to try to translate literally. Rather, I should read a paragraph, think about it, and, as though I had concocted it myself, write it in English as I might have written it in the first place. I felt that this was more than a little outrageous. After all, who was I to equate myself in any way at all with such a great man? I made a mental note to look for opportunities to compromise.

And so, once I had returned to Melbourne, I started work on this exciting project. Atindra-babu had said that if I translated only a page a day, I could get a first draft done in less than a year and a half. This was quite persuasive encouragement, but there were times when a page a day was asking too much of myself. This was my first extensive piece of translation, and Bengali is quite different from any European language I have had anything to do with. I was visiting Atindra-babu for a checking session every second weekend or so, and those sessions proved very helpful. Still, I would have to be patient. And then, after a year, the project was upgraded to Ph.D. status.

Of course, the translation would be simply an appendix to the thesis. The major part of the whole work – major in importance, though certainly not in magnitude – would take quite some time after the translation had been finished. I was prepared for this and not particularly urged by any need to hurry, having become part of Niharranjan's ancient Bengali world, as it were; quite frankly, I liked it there and felt remarkably comfortable in it. I had no urge to get out of it.

Having achieved some familiarity with Bangalir Itihas (whose title I translated literally as History of the Bengali People), I needed to start thinking of Niharranjan Ray as a historian. I remembered, as an earnest schoolboy, finding comfort in the simplicity of Thomas Carlyle's dictum declaring history to be the story of great men and their deeds. Now, having read Niharranjan Ray's history, I was troubled by two words: "great men." I was prompted to wonder if there had been no great women in the past and whether greatness was really necessary to attain historical worthiness.

Some years before Ray came to write his History, G. M. Trevelyan turned English historiography on its head with his English Social History, a monumental work that gave central historical roles to hosts of players from the non-privileged classes. Bangalir Itihas does, indeed, bring kings, for example, into the scheme of things, though not so much in their own right; rather, royal worthiness is assessed by what kingship might have done for society as a whole, and that obviously includes the common people. So, Ray's History soon came to be known as 'history from the bottom' as distinct from Carlyle's 'history from the top'.

This distinction extended from subject matter to sources. The major players in 'history from the top' wrote documents – edicts, treaties, memoirs, and the like. However, most of the stars of 'history from the bottom' could neither read nor write, so their later historians would not be able to lose themselves in documents dealing with their roles in history. Of course, documentary sources that had a pan-Hindu (and, a little later, Buddhist and Jain) pertinence and were as significant to the history of the Bengalis as to the rest of the broader Hindu community were naturally used by Ray wherever it was appropriate. However, he was quick to respect the notion that records of people's lives did not have to be documentary to make them historically significant, nor was the story told by documentary sources necessarily superior to whatever could be gleaned from less orthodox sources. Agricultural implements and rudimentary tools, for example, came to tell many stories, as did artistic items such as engravings on a variety of surfaces, relief sculptures, and icons. And folkloric 'literature' – children's rhymes, folksongs, and stories passed down in oral tradition – bore a wealth of mysteries from the past for perceptive modern scholars to unravel. Ray's History of the Bengali People and his fresh historiography helped to usher in a new era of historical scholarship.

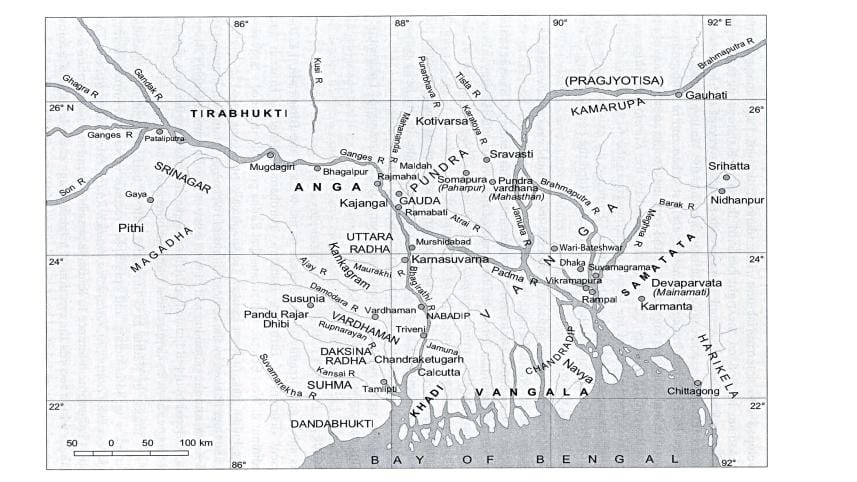

A truly notable feature of Ray's History is its literary value. The prose is incisive, decorative without being flowery, elegant, and at times majestic in style. But its most prominent strength is its content, for in his selection, arrangement, and treatment of subject matter, Niharranjan enables the long-past adi parva of his beloved Bengal to flourish again in the pages of his classic work. He introduces us to the earliest Bengalis he can find. He describes the land that gave them sustenance and which they learned to use to make themselves and successive generations thrive. He shows us how they developed an economy, first as agriculturalists, then as craftsmen and traders. He describes how they ordered their society and provided for its accommodation in villages and towns. He helps us to share, albeit from a great temporal distance, their everyday lives, their pleasures, and their creativity. And he interprets their contemplative life and their reaching out to the spiritual beyond. In all, it is a recreation of the fabulous richness of a distant world, yet one that forms the foundation of what many revere as contemporary Bengali nationalism.

It is interesting to observe that Niharranjan Ray started his adult life as a librarian and ended it as one of India's eminent polymaths. Indeed, given the sumptuous variety of the substance of his History of the Bengali People, it should be no surprise that the man's own mind encompassed a luxuriant range of academic and artistic interests. A quick glance at his immense bibliography reveals an expert understanding of Indian sculpture, Mughal miniature painting, East Indian bronzes, art in Burma, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, the life and literature of Tagore, and much more. In a world in which so many people continue to see increasingly narrow specialization as a worthy writer's raison d'être, the contribution of Niharranjan Ray to modern India and Bangladesh's understanding and appreciation of themselves is an incandescent reminder of the existence of much further-flung boundaries in the pursuit of the humanities.

References

History of the Bengali People, Orient Longman, Calcutta, 1994; second edition, Orient BlackSwan, New Delhi, 2013.

Niharranjan Ray, Makers of Indian Literature, Sahitya Akademi, Calcutta, 1997.

Dr. John W. Hood is a film critic, translator, and former teacher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments