H. H. Risley and Bengal, 1873-1911

Sir Herbert Hope Risley (1851-1911) – who signed himself 'H. H. Risley' – was a member of the Indian Civil Service (ICS) who became British India's pre-eminent anthropologist. How anthropologists and sociologists understand a society is always influenced by the people they come to know best, as well as their own preconceptions, and this was as true of colonial anthropologists as it is of their post-colonial contemporaries. For Risley, who started his ICS career in Bengal in 1873, the most important group of people was the bhadralok, the English-educated, urban, professional middle class, whose members were almost all Hindus from the high-status Brahman, Baidya and Kayastha castes. In Bengal, most Indian subordinate government officials and clerks, as well as other professionals, such as teachers and lawyers, belonged to the bhadralok; so, too, did the leaders and supporters of the Indian National Congress, which was founded in 1885. Risley's relationship with the bhadralok and his attitude towards it, were very ambivalent, but he still had a particular affinity with its members that initially owed much to his early life in England.

Risley was born in Buckinghamshire, the son of a Church of England village parson. He was educated at Winchester College, the oldest elite public school, followed by New College, Oxford. His uncle, grandfather and great-grandfather were Anglican priests like his father, and all four had been students at Winchester and New College. They all owed their priestly livings and college places to family connections or other forms of patronage. But in the 1850s, both colleges underwent reform and Herbert Risley was awarded scholarships at them because he was successful in their new entrance examinations. In 1855, too, an open competitive examination for the ICS was introduced to replace the old nomination system. Risley therefore belonged to the first generation of Englishmen whose education and professional employment depended not on patronage but meritocratic success. Nonetheless, old ideas about divinely-ordained, hierarchical society still persisted in rural southern England. The landed gentry, allied with the clergy, virtually ruled the countryside and the mass of agricultural labourers subsisted in extreme poverty. Risley, who was always aware of his own elevated class status, probably found inequality and traditional hierarchy in India quite familiar.

Rather like Risley, many members of the bhadralok came from an ancient landholding and priestly gentry that traditionally respected education and learning. By the late nineteenth century, they also lived in a modern world in which an individual's education and employment were increasingly allocated by competitive examinations and bureaucratic rules. Hence there was a kind of class affinity between Risley and the bhadralok, and his inconsistent disposition towards it was a critical factor in how he understood India, both as an anthropologist and a civil servant.

The Anthropology of Caste

Bengal, the largest province in British India in the late nineteenth century, included present-day Bangladesh, and West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and parts of Odisha in India. Risley started as a junior district officer in rural Midnapore district in 1873-75. In 1876, he was transferred to the Bengal government's secretariat in Calcutta for three years. In his next posting in 1880-84, he was a district officer in Manbhum district in Chota Nagpur, which had a large population of Adivasi Santals and Bhumijs. This was his last period as a district officer, except for six months in Darjeeling district in 1889. Unlike most ICS officers, who spent longer in the districts, almost all Risley's career after 1889 was in the Bengal or Indian secretariats. Because the great majority of the secretariats' Indian staff belonged to the Bengali Hindu high castes of the bhadralok, Risley came to know them best. He was also fairly well acquainted with some tribal communities, but not with the mass of ordinary, middle- and low-caste villagers in lower Bengal, or with the province's large Muslim population.

Risley conducted an ethnographic inquiry into the province's castes and tribes in 1885-88. District officers and their staff, who made up Risley's roster of 188 'correspondents', sent him most of his ethnographic information, especially on caste and marriage, and 'social precedence' or caste ranking. Among the correspondents, there were 129 named Indians, 26 Europeans and 33 men listed only by their positions. Of the named Indians, 102 were definitely or probably Brahmans, Baidyas or Kayasthas, 18 were other Hindus and nine were Muslims. Hence the majority of correspondents belonged to the bhadralok. Risley also collected anthropometric data to investigate the racial composition of the Bengali population and to try to show that caste status was correlated with racial admixture.

Risley's findings were published in The Tribes and Castes of Bengal in 1891. Its two ethnographic volumes contained a glossary with entries on individual tribes and castes, and their subdivisions, preceded by an introduction on 'caste in relation to marriage'. He had hoped to produce 'tables of precedence of castes', but could not do so because there were countless variations and disagreements in his correspondents' voluminous evidence. The glossary had a male gender bias and curiously little material on Muslims. It also described the Brahmans, Baidyas and Kayasthas as the three 'highest and most intelligent' castes, a patent expression of the glossary's elitist bias, which combined Risley's English class prejudice against the uneducated lower orders with the bhadralok's Brahmanical outlook. Thus he and his correspondents all conceptualised castes as discrete, reified groups that could be clearly ranked with Brahmans at the top. Nonetheless, despite its defects and biases, the work contained a great deal of valuable ethnographic evidence and it brought Risley recognition as British India's leading anthropologist.

In 1898, Risley was promoted to the government of India and one year later was seconded as the 1901 census commissioner. He wanted ethnographic inquiry to be central in the census and also decided that castes should be classified by 'social precedence', rather than occupation as in 1891, so that he instructed provincial census superintendents to collect comparative data on caste ranking. But because he moved to the Home department in 1902, Risley could not finish the census report, although he did write the chapter on caste, tribe and race, which he edited for his 1908 book, The People of India.

Risley had argued in 1891 that the caste system originated in the racial inequality between the more 'advanced', fair-skinned Aryans and more 'primitive', darker non-Aryans, primarily Dravidians, and also that social precedence was correlated with race because the highest castes had predominantly Aryan ancestry and the lowest predominantly Dravidian. A decade later, however, he doubted whether the 'Aryan race' ever really existed and modified his theory to contend – more like a modern social scientist – that caste originated in the fiction that skin colour differences indicated distinctions of race and social status. On the other hand, despite copious census evidence that caste ranking varied regionally and was always disputable, Risley never acknowledged that it could not be specified in 'tables of precedence'. Criticism of this and other flaws in his work, especially his wrongheaded racial theory, has generally overshadowed Risley's significant contributions to the anthropological understanding of caste.

Combating Indian Nationalism

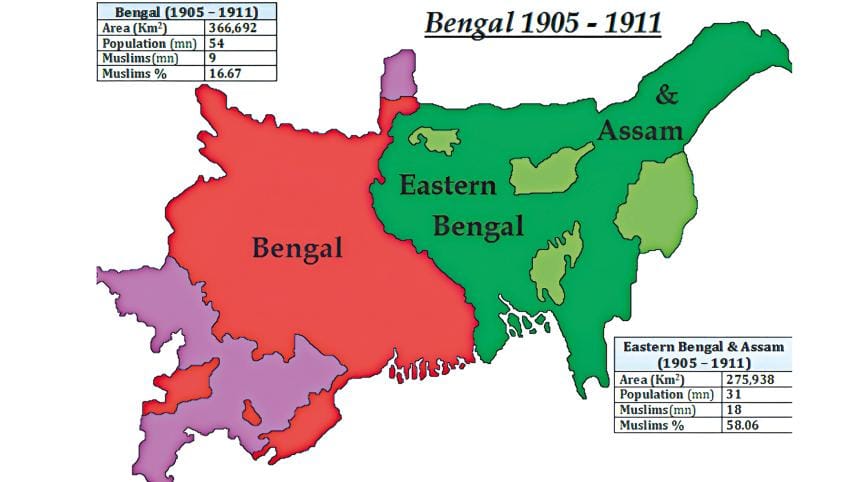

Between 1891 and 1898, Risley was the secretary of the Bengal government's Financial and Municipal departments. One important issue he handled with was a contentious bill to reorganise Calcutta's municipal administration by reducing the powers of its elected commissioners, including the bhadralok Congress politicians among them, who allegedly blocked any effective decision making. These powers were diminished further when Curzon intervened to make the bill more radical after he became the viceroy in 1899. In 1902, Curzon selected Risley as the imperial government's Home secretary. In this powerful position, Risley played a vital role in formulating policy on numerous major issues, including higher education reform, which was especially urgent in Calcutta University, whose senate was reportedly controlled by 'politicised lawyers' and absentee members with no academic qualifications. Congressmen, however, insisted that the government was really seeking to oust its supporters from Calcutta's university, much as it previously did in the municipality. Soon afterwards, in late 1903, Risley announced the proposals for the 'reconstitution' of Bengal and Assam. The Partition of Bengal, which was completed in 1905 after Risley drew up the final plan, was the most controversial of all Curzon's policies, and it especially infuriated bhadralok members of the Congress, who saw it as an assault on Bengali society and culture, as well as a stratagem to weaken the organisation by separating its leaders and supporters in east Bengal from those in the west. Risley admired Curzon and shared his hostility to Indian nationalism and the Congress, but unlike the viceroy he had considerable sympathy for the bhadralok's position in society and never poured contempt on 'babus' and the class as a whole.

In the end, the Partition of Bengal was a political failure. The swadeshi movement against it developed into wider hostility to British rule after partition was implemented, although many Muslims in east Bengal favoured the new arrangement. But the Partition also created separate Hindu- and Muslim-majority provinces, which tended to worsen relations between the two groups and indirectly engendered the communal violence that blighted Bengal for decades. When Minto replaced Curzon as the viceroy in 1905, Risley stayed on as Home secretary and introduced further repressive measures to quash anti-British protests and 'sedition'. But John Morley, the secretary of state, insisted on reform as well. In negotiating the Morley-Minto legislative councils reform enacted in 1909, Minto and Risley acknowledged, unlike the diehard Curzon, that some concessions to 'moderate' Congressmen were politically necessary. Thus the proposals for the new councils were intended to satisfy the 'educated classes', such as the bhadralok, as well as 'loyalist' landlords and Muslim opponents of the Congress, who were granted separate 'class electorates'. Risley expediently justified them for Muslims by asserting that they formed 'an absolutely separate community', even though ethnographic data, as he knew, showed they did not. In general, though, partly because he knew too little about them, Risley tended to be less sympathetic to Muslim interests than Minto or many British officials.

When the new viceroy's council first convened in 1910, Risley introduced a revised Press Act to further deter newspapers from inciting 'sedition'. It was his last official action before retiring from the ICS and returning to London, where he worked in the India Office before his death in 1911. In his council speech, he vigorously defended British rule and insisted on the need for 'cordial and intimate' relationships between the government and the 'educated community'. And he also justified the new law with illustrations likely to strike a chord in the council members from the bhadralok, the group of people who shaped his understanding of Indian society and politics throughout his long career.

Chris Fuller is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the author of Anthropologist and Imperialist: H. H. Risley and British India, 1873-1911, published by Social Science Press in New Delhi in 2023.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments