In a city called Elias

In a city called Elias, there is no beginning and there is no end—"it lives imperishably." The past and the dead are as vital as the rank waters of the Buriganga. There are only waves that rise and come tumbling down, and rise again, with the occasional force of a tsunami. Only then do the wretched and the trodden become lions, and the concatenated jonjal of the social contract is rattled. It was 1969, and Dhaka was swept by "tsunamis of a thousand waves."

1969 was the year of revolution for Bengali identity and rights against the repressive Pakistani regime. Akhtaruzzaman Elias's literary masterpiece, Chilekothar Sepai (The Sepai in the Rooftop Room), published some seventeen years later, traces that revolution through the lives of colourful characters inhabiting the old city of Dhaka.

When the country burns, writes Elias, its searing heat is felt most intensely in Dhaka. A revolution overpowers the city. Slogans reverberate amidst bursts of gunshots. "Tomar amar thikana, Padma, Meghna, Jamuna." Yet it is the city, Khaliquzzaman Elias remarks of his brother's work, that lives imperishably in Chilekothar Sepai. In the novel, one is brought face to face with a sharp-eyed brilliance in seeing and rendering the city. Reading Elias, one no longer looks upon the usual architecture of the city—a ramshackle house, a rooftop room, a tortured lane, a dreary drain, or a "widowed road"—with nonchalance. Having followed the city as an architect and writer, I find Chilekothar Sepai a masterful psychogeography of a talmatal place.

As we open the first pages of the book, we are already in the middle of the tsunami, confronted with a dead body—a student shot by the police. We are also in the heart of Elias's city, the spatial locus of Sepai. A provincial capital is on the verge of metamorphosis; it is about to uncoil from its placid omphalos. By the 1960s, the city of Dhaka had many cores, but the one Elias chose to anoint in his book lies within the nested city of old Dhaka. The nested city is like an onion, with one skin enfolding the next.

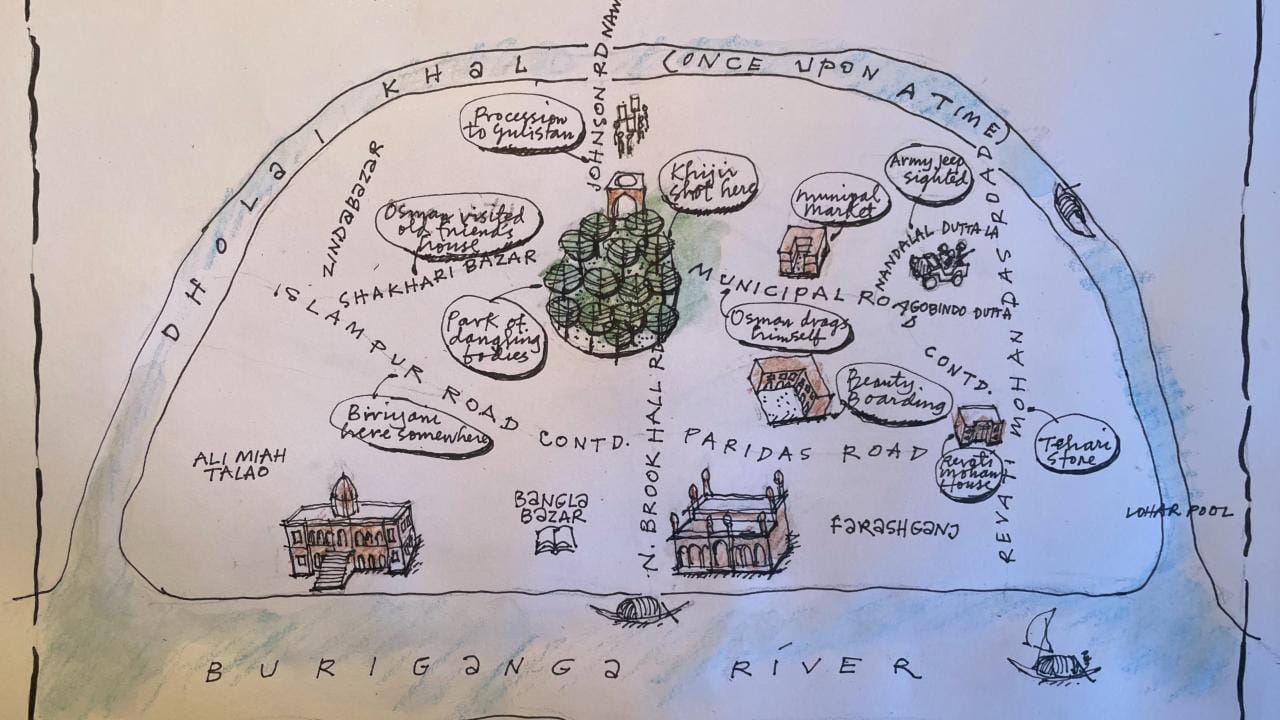

Although Elias takes us on excursions to other parts of the city, the centre of this enigmatic onion is an area roughly bordered by the old Dholai Khal, the Buriganga to the south, and Northbrooke Hall Road and Nawabur Road to the west. I am not the first person, and I certainly will not be the last, to speak of the spatial and urban dimensions of Chilekothar Sepai, for Elias has given us an enduring map with which to embark on many journeys while navigating Dhaka.

Often described as a psycho-political novel, the landscape of Chilekotha is too vast to be fully explored in a short essay. Yet a few summary observations may be offered. The setting of the book is the old quarters of Dhaka (the omphalos), with a brief mirrored sojourn in a northern village near the Brahmaputra River. The story is as much a damning dissection of Dhaka's various social clouts and classes as it is a penetrating psychological exposé of a troubled soul. In his archaeology of 1969, Elias advances two political truisms: that revolutions have evolutions, and that a promising class struggle is upended by a bourgeois movement.

At the centre of the torrent that strikes Dhaka stands the protagonist Osman Gani, living as a resident in a rooftop attic. Osman's world is a walkable city, punctuated only by occasional rickshaw rides. No matter how much he walks the streets of Dhaka—in memory, imagination, or lived experience—and witnesses an urban theatre unfold, Osman remains both detached from the ongoing revolution and unmoored from the social life of the city. Not born a citizen of Dhaka, nor of a village in Bangladesh—having grown up instead in a village in West Bengal—he feels listless and homeless, desperately seeking communion with either an individual or an ideology. His relationship with the crowd—the pulsating mass moving through the city—is dubious, and his intimacy with others remains fragile.

Other characters illuminate the social tapestry. Anowar, the political activist, is a version of Osman but without the latter's psychological perturbation; the landlord Rahmatullah Sardar stands as the emblem of the conniving political class; the contractor who helps fill up Dholai Khal to make a road there is also mirrored in the figure of Khoybar Gazi in the village—a character that later expands into a fuller portrayal in Elias's magnum opus Khwabnama; Chengtu emerges as the village rebel poised to upend the status quo; Alauddin appears as Rahmatullah's nephew, a nationalist activist yet not averse to marrying the daughter of his despicable uncle; and there are the few female characters, often known simply as Jummoner Ma or Khijirer Ma, who endure economic hardship, marital abuse, and lecherous advances.

Joyce claimed, grandly, that if Dublin were destroyed, it could be rebuilt from the pages of Ulysses. As with Dublin in Ulysses—though without its mesmerising pictorial quality—Chilekotha reveals a Dhaka discovered through walking, unlike any other work in Bangla.

And, of course, there is the sparkling character of Haddi Khijir Ali, who, with his volatile nature—holding a pair of pliers in one hand and a screwdriver in the other, and on occasion a can of kerosene—becomes the portrait of the impetuous proletariat, always ready to join the crowd milieu and stand up to injustice. Khijir is the personification of the tumultuous city.

While all the characters are part of a revolutionary theatre, only Osman exposes the deep interiors of a Kafkaesque mind. An aspiration incarnate of the fidgety middle class, he is torn between revolution and self-preservation. He is either introspecting alone in his chilekotha, unraveling by himself, or ambulating the streets in quest of connection. Only gradually does Osman discover his affinity with the anarchic figure of Haddi Khijir—the skeletal man who is both homeless and deeply rooted in Dhaka.

We come to see how the social theatre unfolds in rhythm with the city itself. In Chilekothar Sepai, there is an oscillation between two spatial realms—the street and the rooftop of a building. These two realms, however, generate three social situations: the street, with the heaving crowd-mass acting literally as the tsunami; the rooftop, with the attic or rooftop room functioning as a kind of space shuttle, quietly and invisibly drifting close to the skies; and the intermediate zone of the house, with its everyday domestic movements.

From his solitary rooftop room, where he is mostly alone and confronts his demons and desires, Osman eventually descends into the street in a surprising climax to the novel. The rooftop room also signals a tangential space occupied by a perpetual outsider. The chilekotha further evokes, for me, the image of a Buddhist stupa. At the very top of a stupa—regarded as an embodiment of transcendence—there is a small structure called the harmika, literally the "little house". It is often described as the final house in the stages of Buddhahood. Close to asman, the chilekotha becomes a kind of harmika, from which there is only a descent down to the turbulent street. It is transcendence in reverse.

Osman's building is three storeys high and, as we are told, it is "hopeless". There is no open space in front; the house begins immediately after the drain. A short doorway serves as the entrance, making the house resemble a fort. The three storeys accommodate a shoe factory at ground level and rental units on the upper two floors, with rooms awkwardly divided by cardboard and bamboo screen partitions. With a factory below and a rickshaw garage next door, the building exemplifies the impromptu mixed-use character of old Dhaka's quarters. The rich, the aspirational, and the utterly poor live there side by side in a mutually dependent and often anxious arrangement.

This is how Elias describes Osman's chilekotha on the roof:

"There is only one room on the roof; there is no kitchen or toilet. To excrete or bathe, one needs to stand in a queue on the ground floor [Osman urinates in a corner of the roof while brushing]. But Osman's room has plenty of light and air. There are two doors—one facing the stairs and another opening onto the roof. The roof is rather large, with railings all around; the railing at the front is high. Standing on one side, the street in front looks wonderful. Directly opposite the road is a one-storey house, rather large and similarly unwieldy. A masjid straddles that house, and a signboard on the veranda bears the name Haqqa Nur Maktab in Bangla and Arabic. From time to time, Osman comes up to the roof. Standing there, the roof beneath his feet briefly appears desolate amidst the cramped houses. He quickly slithers back to his room."

To me, the novel conveys the ambulatory layout of James Joyce's Ulysses and an urban panorama in which a "sociologically rich realism depicts the tensions of city life" (as in the work of the American novelist Richard Price). We learn from Elias's friends about his readings of Joyce's work. Ulysses captures life in a city over a single day, in which the principal characters—especially Leopold Bloom—move through particular locations and streets in Dublin, described with meticulous accuracy. Writing the famous novel from Paris, Joyce would ask his friends back in Dublin to describe the details of a shopfront or a street corner. Joyce claimed, grandly, that if Dublin were destroyed, it could be rebuilt from the pages of Ulysses. As with Dublin in Ulysses—though without its mesmerising pictorial quality—Chilekotha reveals a Dhaka discovered through walking, unlike any other work in Bangla.

The work of poet Shamsur Rahman also explores the Dhaka of 1969. In an essay, Elias admits to being inspired by the poet's work, especially Smritir Shohor, but highlights the difference between poetic melancholy and detached description. To unearth the mysteries of life, the poet selects the city and sees it through the eyes of a curious visitor (probashi) or an anxious lover (pronoi). Yet the city is rendered as a wreck in the poem Towards a Devastated City—simply looking at it becomes nerve-racking. If the poet harboured a melancholic love for the city, this is not the case for Elias. What a novelist needs in order to write about "garbage-filled empty streets clad in moonlight" is nirliptota, a cool detachment.

Laxmibazar is the omphalos in the city called Elias, from where the city spreads outward through streets and lanes, verandas and roof terraces, chilekothas and pigeon coops. In April, a friend and I went looking for Elias's Dhaka. I had returned to that area after about twenty-five years. It was nothing like the Bloomsbury wanderings haunting Joyce's Dublin in 1954, when Joyce aficionados undertook a pilgrimage through the streets and spaces described in Ulysses (an event that has since become annual, taking place on June 16, the day on which Ulysses is set).

In the city of Elias, rickshaws jostled with thelagaris, hawkers cried themselves hoarse, metal shops jingled and jangled, and pedestrians navigated like ballerinas—even when the street was not transformed into a rain-made puddlescape. Shamsur Rahman, writing some sixty years ago, vividly captures the city when it lies empty during a hartal: "Finding the streets of the city of Dacca empty, I made up, as I strolled along, so many things, giving free rein to my fancy: a golden fish suddenly leaped up on the tip of my finger, began to grow and then flew away to a tender garden to seek out some different shape in the boudoir of endless flowers. As I strolled along, I wiped out the signboards and set there the shining lines of my favourite poems; hung on each street corner Picasso, Matisse and Kandinsky." [From the poem Strike.]

My friend and I, however, encountered a city in full motion. Not quite flâneur-like, nor quite painting Picasso onto poster-splattered plastered walls, we quickly became part of a hurried tableau.

We began at Bahadur Shah Park, which forms a perfect fulcrum: one arm leads to Municipal Road and Subhas Bose Road and into the depths of Elias's city; another turns towards the waters of the Buriganga; and a third stretches north to Gulistan and beyond, towards the threshold of the new city that Osman and his friends often frequented for their addas. Except for a trip or two to Islampur and Shakhari Bazar, Chilekotha largely perambulates around Laxmibazar. We reached the gate of St Gregory's High School on Municipal Road and stood before the old school, recalling the time when I was a student there—uncannily, in the year 1969, that tumultuous moment when the youth of Dhaka poured out from halls, messes, and classrooms to shake the edifice of the strange nation called Pakistan. A vendor selling chaat, amli, and phuchka was still stationed outside the gate.

We walked east along Municipal Road. I did not tell my walking companion that I was looking for a particular building from my schooldays. Not having seen it for some distance, I thought it had suffered the bulldozer fate of many of Dhaka's buildings. But there it was—old and reliable, tattered and glorious at the same time—a three-storey structure with a courtyard: the Municipal Market. I recalled an eatery on the ground floor that we frequented after school, the one that served memorable Mughlai parathas.

Throughout Chilekotha, there are references to eateries and restaurants that archive Dhaka's food haunts: breakfast with naan and paya at Islamia Restaurant; raucous addas at Central Hotel and Amjadia; sheekh kebabs in Thatari Bazar; tea at Rex; fish with patla jhol at Anandmoyee Hindu Hotel; murag pulao at Palwan's shop; haleem in Nawabpur; paratha and kaleeza at Nigar; roti gost at Nejami; a plate of rice at Provincial in Stadium; pastries at Capital or Shaheen Restaurant; and sweetmeats opposite Jorpur Lane.

We entered Nandalal Dutta Lane, narrow and dusty, and walked past Shaheed Suhrawardy College—once known as Quaid-e-Azam College, inaugurated by Sher-e-Bangla himself (what a line-up, I thought, for such a small lane). Elias writes: "Pichchis (kids) playing cricket at the mouth of a lane near Quaid-e-Azam College, but rush to puncture a rickshaw wheel whenever one appears, shouting 'down with Ayub shahi, Monem shahi.' Suddenly, an open-top jeep appeared from Gobindo Dutta Lane with Punjabi, Baloch, and Bengali soldiers wearing helmets and carrying machine guns. In a wink, the pichchis disappeared down Nandalal Dutta Lane and Panchbhai Ghat Lane."

Turning east onto Revati Mohan Das Road, which is equally narrow and lined with shops of one kind or another, it began to rain, and we took shelter in one of the ubiquitous metal shops. Giant steel pulleys and chains hung everywhere. The man inside invited us to sit. We preferred to stand on the threshold and watch people scurrying along the road as the rain continued. Realising that the rain would not relent, we took a rickshaw so that we could continue our journey. We went south along Revati Mohan Das Road and then turned right onto Paridas Lane. The grand house of an old merchant family that gave the road its name still stood at the intersection, though it had lost its former meaning. Neither the streetscape nor the traffic had changed much.

The rain had slowed by the time we stopped near Beauty Boarding, the famous haunt that offered meals and gathering spaces for Elias and other writers of his time, including Shamsur Rahman. Chilekotha's description of the close proximity of house, rickshaw garage, and tehari shop came vividly alive in the neighbourhood. We ordered rice, daal, and fried rui from Beauty's wall menu and wondered about the spirits of times past lodged in the fraying two-storey building.

The Buriganga lay just steps away, although Elias does not speak much of the river unless its waters rise to the song of the revolution's fire. We walked south to reach Northbrooke Hall and the riverbank, and then took a rickshaw back to Bahadur Shah Park. Sadarghat remained as boisterous as ever when I had set foot there many years ago.

Subhas Bose Avenue, Hemendra Das Road, Gobindo Dutta Lane, Patla Khan Lane, Panchbhai Ghat Lane, Narinda Pool, Golak Pal Lane off Nawabpur—the streets read like names from a secret map. Golak Pal Lane, Pannu Sardar Lane, Thakur Das Lane, Tipu Sultan Road, Padma Nidhi Lane: mohollas staggered between reconciliation with a ragged old past and a hodgepodge present.

In a city called Elias, the dead dangle with the living. They inhabit the same urban space, most often oblivious to one another, but in times of tsunamis, they rise and march together. The book ends with the spectre of the deceased Khijir, killed earlier in a police firing near Bahadur Shah Park, and his rickety, chassis-like body beckoning Osman to join him and his dead comrades, who are suspended effortlessly a few feet above the city. The homeless Khijir will take Osman home.

In a dance of the dead, levitating rebels arrive from different historical times, from different tsunamis that shook the imperishable city—people from Tantibazar rising from the cold depths of a lost canal; people thrashed by the Mughals, Moghs, and beniyas; fighting faqirs of Majnu Shah; Muslin weavers thrusting up their arms with amputated thumbs; sepoys from Meerut, Bareilly, Sandwip, and Goalundo hanged in Victoria Park; the trade unionist Somen Chanda killed by hooligans; Barkat shot dead in 1952.

In the first story of Joyce's Dubliners, a character looks up at a building from the street and peers into an interior life through the frames of a window. In the last story of the book, in a reversal, the character Gabriel is inside a room and looks out of the window. "Other forms were near. His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself which these dead had one time reared and lived in was dissolving and dwindling."

In a scene that is at once fabulous and cinematic, magical and chilling, Chilekothar Sepai ends near the fulcrum of the city, Bahadur Shah Park, where rebel bodies dangle like the many steel pulleys I saw earlier. The solid world is dissolving. Existence, as known, is flickering. The imperishable becomes impalpable. Bursting out of his roof-room in a catatonic daze (or perhaps in catharsis), tumbling down the stairs, breaking down the main door, and toppling into the street, Osman rushes out to follow his floating friend with pliers, ready to accompany him beyond the realm of the city. No longer recognisable, he drags himself along Municipal Road, past the Mughlai shop and my old school, towards the cursed park—a path I had taken last April, though in the opposite direction, as an act of homage.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and writer and directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements. He is the author of The Mother Tongue of Architecture: Selected Writings.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.