Bangladesh and 1971

Shono ekti Mujibarer theke/ Lokkho Mujibarer konthoswarer dhwani-protidhwani/ akashe batashe othe roni/ Bangladesh, amar Bangladesh….

Listen, from one Mujibur/ A thousand Mujib's voices rise/ The sounds and echoes of those voices/ Ring out through the wind and the sky/ Bangladesh, my Bangladesh….

(Lyrics by Gouriprasanna Majumdar, sung by Anshuman Roy, 1971)

In the historical memory of South Asia, 1971 is a year that is worth remembering for many reasons: foremost among them is the birth of Bangladesh as an independent state, breaking her ties with Pakistan after months of a bitterly fought war that had implications far beyond national borders.

The Liberation war had an obvious leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, whose socialist, secular ideology gave focus to the strife. In one of his famous speeches he reiterated:

No country or nation has shed this much blood for independence. Our blood and our independence will become useless if we can't put smiles on the faces of the people of this country. If we want to build an exploitation-free society, we must build our country based on the principles of nationalism, democracy, socialism and secularism…..Today, our vow must be that we must protect our independence with blood, the independence that we brought with our blood. (Translation by Ahmed Ahsanuzzaman)

Mujibur Rahman's speech touched upon issues that were ideologically and politically significant for the new nation.

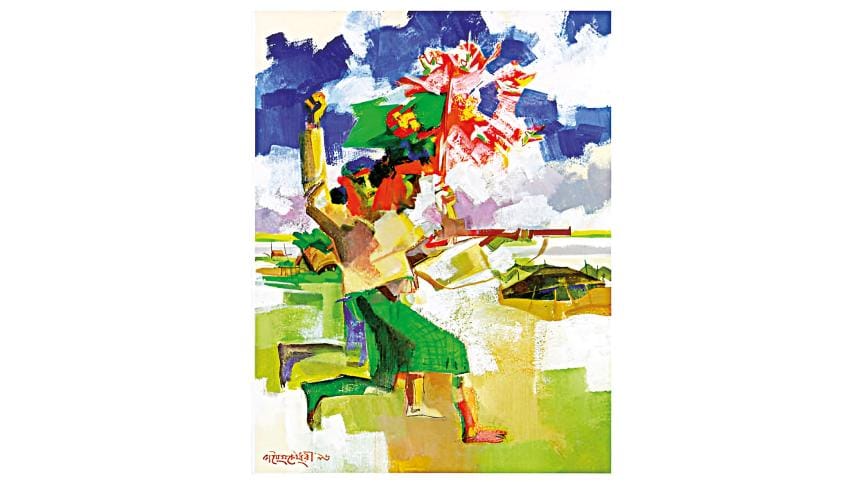

The Liberation war was often termed jonojuddho where ordinary people, irrespective of class or creed had taken part. In a compilation of letters from 1971 (Ekattorer Chithi, Prothoma Prokashon, 2009) we can see the extraordinary fervour and commitment to the cause that united the people of Bangladesh. In a letter written on 15th July 1971, an unknown muktijoddha writes from Mymensingh that the Pakistan army had no war policy so the 'marginalized, unarmed peasant, labourer, students and teachers, children and women were being mowed down. This genocide has surpassed many My Lai of Vietnam.' Anjali Lahiri in her memoir, Smriti O Katha, writes how at the Banstala camp, 'the courage, discipline and energy' of the young fighters had moved her indescribably.

Bangladesh will always stand for hope, for her own people and for others elsewhere. Bangladesh's legacy remains bound with that originary moment of linguistic nationalism that overturned the religious fratricide of the 1947 Partition of India.

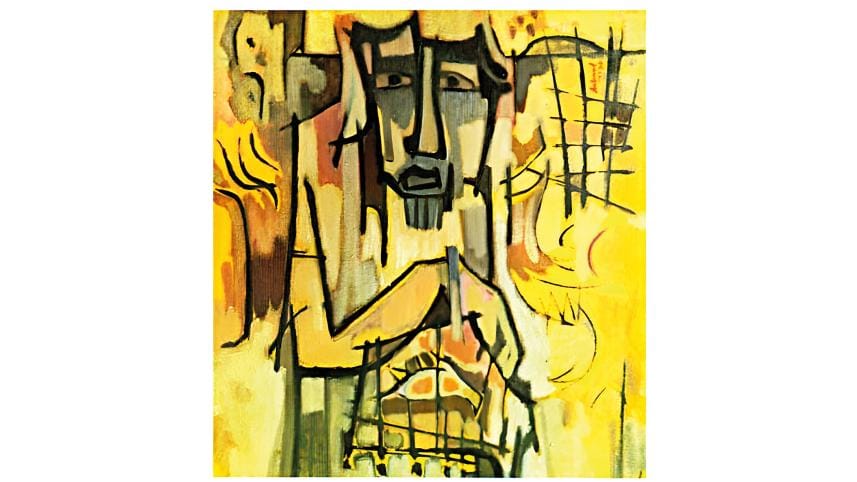

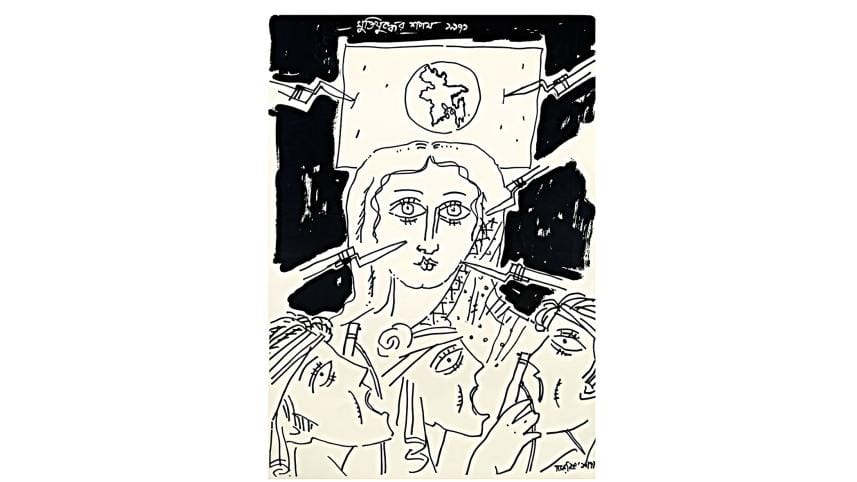

However, recent anthropological, historical and oral history projects in Bangladesh and elsewhere have problematized the aspect of the male gaze just as it has tried to understand the nature of violence that was carried out on the masses. Sharmila Bose's book Dead Reckoning problematized the linear heroic narrative of Bangladesh's national struggle to bring in perspectives and interviews of Pakistani soldiers who had been engaged in the war to 'create a unique chronicling of the 1971 conflict that serves as a basis for non-partisan analysis' while Anam Zakaria's '1971: A People's History from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India' brings measured and thoughtful voices from geographical spaces that speak to each other. The muktijuddho of 1971 continues to exert great cultural and political significance even on later generations. Diasporic Bangladeshi writers like Tahmima Anam talks of her own complicated understanding of it: 'The war was fundamental, a kind of birth not just for the country but for all the too-young people who had willed the country into being.'

The Liberation war has also thrown up issues that have generated thorny debates. After the Partition, a large number of Bihari Muslim refugees who came to settle in East Pakistan, had supported the unity of Pakistan and had taken part in the Pakistan army led genocides. Known as razakars, many of them who survived the war had to face harassment and social marginalization in independent Bangladesh. The Biharis, left behind by the Pakistani Army and refused entry into Pakistan as refugees, had to remain as stateless people in free Bangladesh. Like the forgotten Biharis, hundreds of Hindus who fled to India were initially urged by Sheikh Mujib to return but many didn't and the question of citizenship of the Hindus, especially those belonging to the Namashudra community, who entered India in 1971, continue to be a part of political wrangling in contemporary Indian politics particularly in the states of Assam and West Bengal. Similarly, the ethnic minorities that make up Bangladesh's population like the Chakmas and the Santhals have had little political representation and are outside the ideology of Bengali linguistic and cultural nationalism. Mujib's promise to the country's ethnic minority thus remains a work in progress.

Bangladesh's Liberation War had a great resonance in West Bengal. Artists, doctors and ordinary citizens lent all kinds of support to the cause by setting up relief camps along the border to facilitate refugees and the muktijoddhas, to tend to the wounded and bring relief to the homeless. Following the Declaration of Independence on 10 April 1971, the Provisional Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh was set up in Mujibnagar but the capital-in-exile was Kolkata. The Indian Government, under Indira Gandhi, moved a resolution in Parliament expressing whole-hearted support for the people of East Pakistan. However, one of history's ironies was that West Bengal's own political upheaval, the Naxalite movement of the late 1960s and 70s, had a different trajectory and in many of our memories, 1971 is a year to remember because of a juxtaposition of events and misfortunes. West Bengal, then ruled by a Congress government, had gone on to brutally suppress the Naxal upsurge, by then riddled with factionalism and internal contradictions. By 1971, a large number of young students, labouring poor and political workers were killed or incarcerated in prisons. At that very moment, across the border, the Indian government was aiding a group of Bangla speaking people, mostly young too, who were dreaming to wrest freedom from bondage. The dream of an equitable and just society, which we can call a revolution, thus had two different trajectories and two different outcomes within the same span of historical time. In many ways, 1971 laid bare many contradictions and ironies of historical processes.

The memories, events and nightmares of 1971 have had many inheritors. Like any historical moment that generated sweeping political aftershocks, it has also engendered contested accounts and remembrances: some vivid, others less so, marked by violence, nostalgia, pain and regret. Now, with a passage of time, the inheritors of loss and shame have had the time and space to look back to assess their own culpability and investment in a nation's birth. The water has been muddied with accounts and counter accounts but in all these recriminations and eventual revaluations, the path to reconciliation and peace remains starkly outlined. In the subcontinent's history, Bangladesh will always stand for hope, for her own people and for others, elsewhere. Bangladesh's legacy remains bound with that originary moment of linguistic nationalism that overturned the religious fratricide of the 1947 Partition of India.

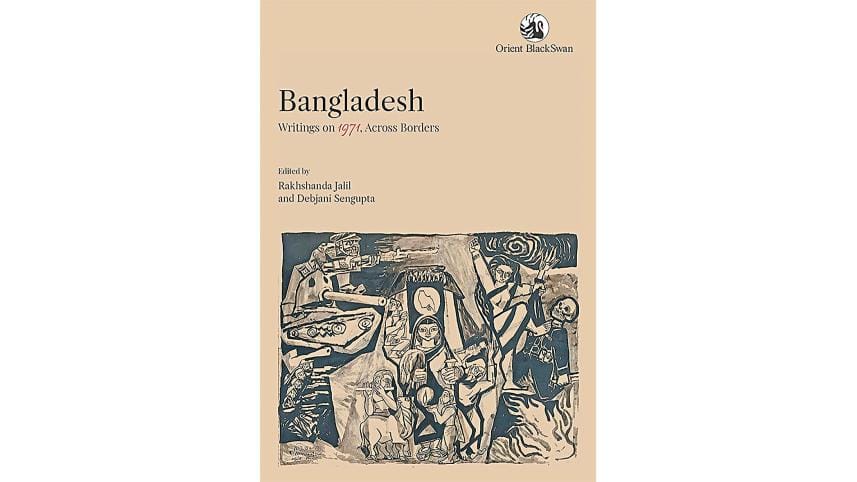

As editors to a volume that collected these narratives of hope and despair, violence and peace, we wanted to see the complexities and nuances of those times captured within the tumult and compromises of ordinary people who were witnesses to historical forces they understood and responded to. In many ways, this anthology of literary writings from Bangladesh, West Bengal and Pakistan is the first of its kind: it brings differing and measured responses to 1971 and allows its readers to see the complex nuances of contested memories. 'Bangladesh: Writings on 1971 Across Borders' therefore tries to bring together remembrances of a Pakistani army personnel who was present in Dhaka (Meher Ali's essay on her grandfather Nadir Ali) and the Naxal movement's subterranean vibrations in Manas Ray's 'The Unputdownable 70s: Memory Matters.' Jan Nisar Akhtar's beautiful words in his poem 'The Bangla Victory' is a paean to people and their humanity, irrespective of political loyalties: 'Dear Bangla: We could not watch you being erased/The blood of camaraderie woke up in every vein' while Naseer Turabi's lines 'He was a fellow traveller but he and I were never compatible' is both ironic and 'dirge-like.'

A reappraisal of 1971 is best articulated in the short fictions of Akhtaruzzaman Elias, Shaheen Akhtar and Wasi Ahmed from Bangladesh. Elias's story 'The Raincoat' (reminiscent of Gogol's 'The Overcoat') is a brilliant exegesis of the fear and the compromises that accompanied the muktijuddho while Akhtar's story 'She Knew the Use of Powdered Red Chillies' is a thoughtful exploration of the ironic trauma of being lauded a birangana. We have dedicated the anthology to the people of Bangladesh, past and present, whose love for their land and language continues to inspire generations; and to the battle weary dreamers who had dropped by the wayside in the years 1971 and beyond:

Tobu guro khwatey choyaye smritir beesh

Yet poison memory oozes from the gaping wound

Debjani Sengupta teaches at IP College for Women, University of Delhi

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments