How to avert the next building tragedy

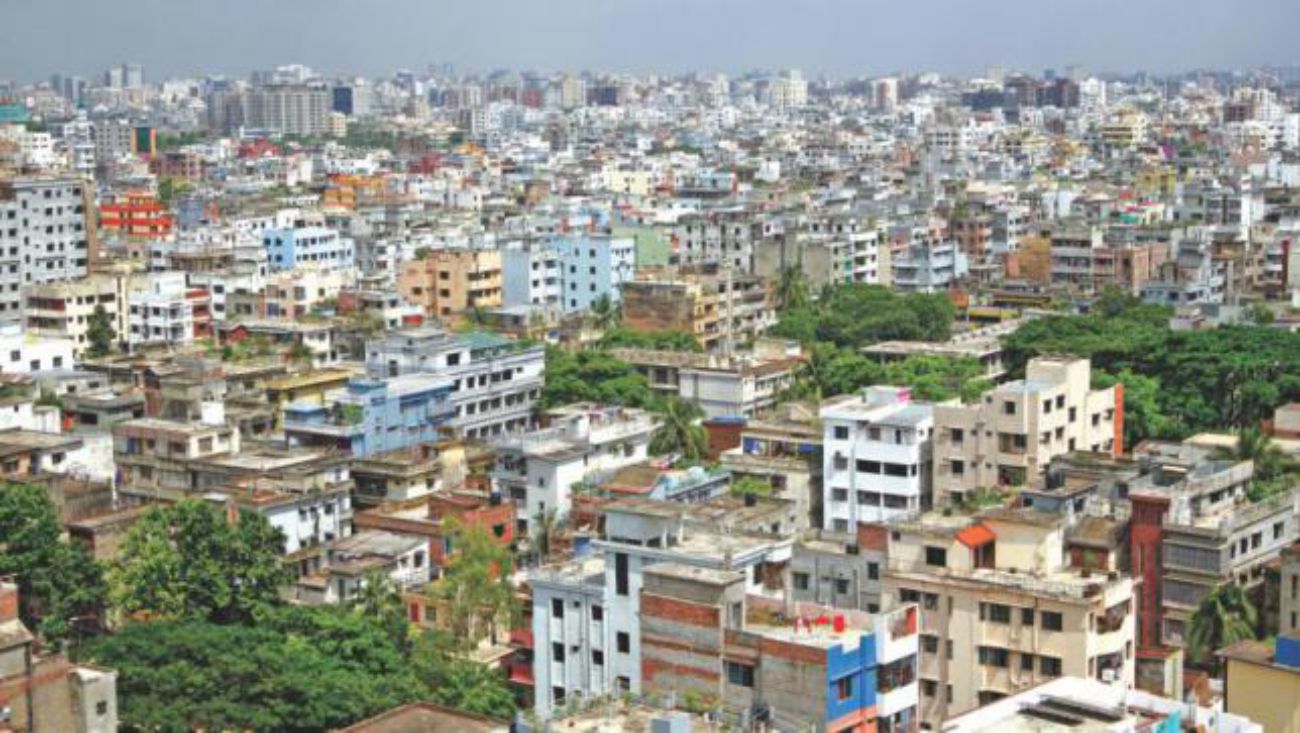

Three accidents in less than three weeks have once again highlighted how vulnerable Dhaka's buildings are to fires, explosions and such disasters. First, there was the fire in Gulshan, which killed two individuals. Then, there was a blast near the Science Lab intersection which killed three. And then came the explosion in Gulistan which killed at least 22 so far. Their locations – one in a posh area, one in a commercial area, and the latest in a crowded area in Old Dhaka – suggest that when it comes to building accidents, no neighbourhood is safe enough. The risk seems to lurk everywhere in this megacity thanks to unplanned urbanisation, blatant violation of building and fire safety regulations, as well as lack of inspection and awareness.

This has been a proven recipe for disaster, and by the look of things, it has been getting worse. As per data from the fire service, there were 19,642 fires in 2018. The number rose to 24,102 last year. If the trend holds, and if the relevant authorities continue to refuse to learn and take preventive actions, it is only a matter of time before tragedy strikes again.

Ours is a city "strewn with ticking time bombs", as the headline of a report by this daily memorably put it. And why not? Given how callously building and fire safety regulations are treated, questions can be asked about the electrical and structural safety of most buildings. Some of the commonly cited reasons for recent fires/explosions include electric short circuit, accumulation of gas in a confined space, poorly maintained air conditioning units, etc. The Gulistan blast has also been blamed on accumulated gas through concealed or disconnected gas lines. There is also the possibility of biogas accumulating in the septic tank or a leaky sewer pipe turning part of the building into a gas chamber, which was somehow ignited. Whatever the reason, it is obvious that it had to do with poor maintenance of the building.

The question is, how many buildings are there with similar conditions? How will residents understand if there is a risk of gas accumulation and of explosion? Lack of awareness is an issue, of course, but as an expert speculated, Titas Gas authorities may have stopped adding the distinctive foul-smelling mercaptan to natural gas making it difficult to detect a leakage. Most buildings in Dhaka also suffer from poor ventilation. Unfortunately, the safety of buildings – including gas connections, electric lines, sewer pipelines, septic tanks, elevators, etc. – is rarely inspected, while fire drills are quite unheard of, making it almost natural for tragedies to occur.

This must be stopped. We urge the relevant authorities, including Wasa, Desa, Rajuk, fire service and the city corporations, to acknowledge the gravity of the danger that residents of this overcrowded city face. As experts have suggested, the government should immediately introduce a practice of providing occupancy certificates after yearly inspection of all buildings. We need a thorough inspection of all residential and commercial buildings, and all measures must be taken to improve their safety. We must also punish those responsible for the frequent building tragedies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments