Continuing flood exposes the fault lines in our response

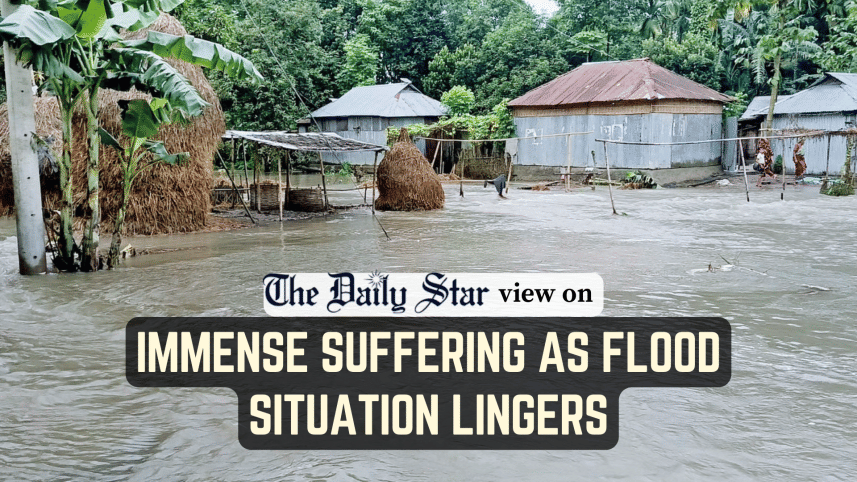

Bangladesh is in the middle of its annual monsoon, so regular news of flooding along with the deaths and destructions that come with it is more or less expected, even though the pain of witnessing so much suffering never goes away. What's harder to accept, however, is when the suffering is exacerbated by things that are in our control. Two developments that have become synonymous with the flood this year, and natural calamities in general of late, are the crisis of relief supplies, especially for those stranded in remote villages, and the fragility of embankments and polders.

As the floods hit new areas, with as many as 20 districts and two million people affected so far, as per an estimate released on Sunday, the cries for aid are getting louder. Many have complained that they were yet to receive government assistance. This could be partly because of transportation and distribution challenges, with the upazila and union parishads in charge of aid deliveries, and partly because of the quantity of provisions allocated. The local administrations and public representatives have a big task here: they must ensure not only sufficient provisions but also proper distribution. And while at it, they must give special attention to those who could not make it to the temporary shelters.

The other development that has caught our attention is how prone to damage many of the embankments and polders are, giving away at the slightest nudge, metaphorically speaking. We have had reports of crude materials like sand-filled geo-bags being dumped to check water flow through some of the collapsed dykes. While the pressure of floodwaters can be intense, especially when rivers flow above danger levels, any structural defence should be designed to withstand the pressure. What's the point of having them then? We must resolve these and other longstanding issues—including the largely ineffective river-dredging programmes that are supposed to help manage water flow and erosions—so that vulnerable communities do not have to suffer so much.

In some of the worst-hit districts, water levels are decreasing but the overall flood situation has not improved yet. In Kurigram and Lalmonirhat, over 1.60 lakh people have been marooned. Farmers have suffered significant losses, with around 6,500 hectares of agricultural land including Aman seedbeds and vegetable fields submerged in Kurigram alone. Meanwhile, over 1,000 educational institutions remain closed in Sylhet and Rangpur regions. At least 10 have died, including two in Jamalpur on Monday. The growing human and economic tolls of the flood are becoming clearer as days pass. The least we can do in such a situation is prepare better, and wisely.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments