Can we climate-proof our coastal towns?

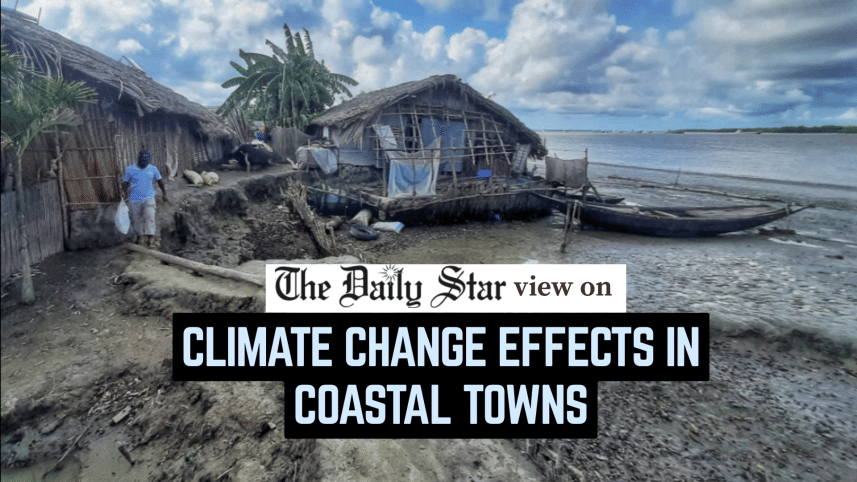

A recent study published in the Journal of Water and Climate Change has brought into focus an often overlooked dimension of climate risk: our coastal towns. According to the Buet-led research team, 22 urban centres across 10 coastal districts now face heightened threats from river erosion, salinity, cyclones, and acute water scarcity, which directly undermine people's livelihoods, health, and social security. While migration to Dhaka gets the most attention, a recent Prothom Alo report shows that coastal upazila towns have become the first destination for climate-displaced families from more vulnerable areas, resulting in heavy population pressure and deteriorating living conditions.

The lived realities described in the report make the severity of this crisis clear. In Satkhira city alone, the population has surged from 1.13 lakh in 2011 to over 2 lakh, with 47 slums now housing families displaced from places like Gabura and Shyamnagar. However, these settlements remain waterlogged for months during the monsoon and lack basic amenities. Similar stories emerge from Khulna, where repeated cyclones, including Aila, Sidr, Amphan and Remal, have forced more than 1.23 lakh people to leave their homes over the past decade and a half. The World Health Organization estimates that over 71 lakh people in Bangladesh were displaced due to climate impacts by 2022, a figure that may rise to 1.33 crore by 2050. These numbers emphasise the urgency of reassessing how we manage vulnerable areas, including coastal towns.

The Buet study identifies towns such as Chalna, Morelganj, Kuakata, Char Fesson, Lalmohan, Kalaroa, Patharghata, Borhanuddin, and Paikgacha as being under high risk due to the combined challenges of population density, poor housing, inadequate water and sanitation, limited transport options, and recurring disasters. Meanwhile, some towns with lower vulnerabilities at present still face high future risk due to exposure to storm surges, embankment breaches, and salinity intrusion. Add to that the fact that unregulated shrimp farming often accelerates embankment damage, worsening displacement. This mismatch between institutional preparedness and the scale of the hazard leaves coastal towns trapped in a cycle of crisis.

Local governments cannot address this challenge through relief operations or isolated interventions alone. What is required is the integration of multi-hazard risk assessments, similar to the approaches outlined by Buet researchers, along with climate-resilient urban planning and stronger municipal governance. There must be durable embankments, safe housing, affordable water supply systems, sustainable drainage, and regulated land use to prevent further ecological damage. Long-term interventions rather than reactive fixes must define our approach. Coastal urban centres are now frontline climate hotspots, and unless the government ensures coordinated investments and proper planning, the ongoing displacement, poverty, and urban breakdown will only intensify.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments