The Krishnachuras in Cambodia

I reached Phnom Penh on a late summer night in 2011 after twenty-some hours of flights from Washington. The airport had a mofussil feel. The immigration officer chose to speak in Khmer, a welcome with the unintended hint that I belonged. As I exited the airport, the half-moon above was bright, the air fresh after a heavy rain, and the road empty except for the construction workers and a few stray dogs.

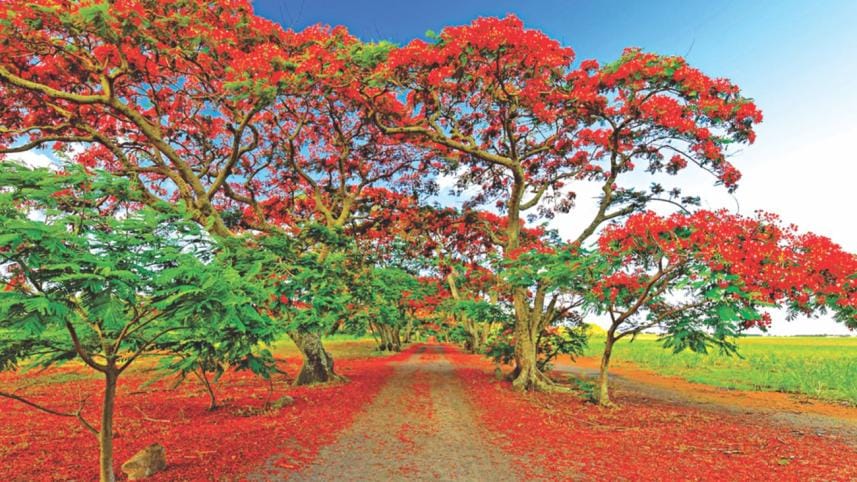

The next morning, from my 10th floor balcony, opened up a panoramic view: the city below was corseted by the Mekong and three other rivers; spanning across Hun Sen park, two rows of krishnachuras were in full bloom, a tango of green leaves and red flowers blowing in the wind. Fittingly, in Khmer, krishnachura is called kangauk (peacock). To my three-year-old, krishnachuras - with their green and red - brought to mind the Bangladeshi flag.

The krishnachuras transported me back to 1980s Dhaka with my father.

Over a quarter century ago, under a krishnachura, and not too far from a 15th-century Sufi shrine in Mirpur, I said my final goodbye to him. From across the pond, the breeze got cooler and heavier as the March drizzle conspired with the maghrib azaan to make the freshly shoveled ground muddy but holy. Fahim, my younger brother, did not fully fathom what was going on. I remember hugging him for a long time after the hasty burial.

My father had suffered for most of my teen years. When we are young, days are short but years long. The fear of loss meant those five years in the hospital felt like an eternity.

We all cope differently after a loss as to the question of why me. Over the years, as I looked for answers, I often felt the urge to write about him, about how I still miss him. Some say words heal by first sculpting our feelings, then by burying them. But writing is a delicate exercise in nostalgia, healing, self-pity, and, unavoidably, narcissism. The balance is never easy.

My father was a gentle, family man, with a thick set of wavy hair and a sense of humour that all of his seven children loved. His sad eyes and wide nose showed Indo-Chinese features.

If a single variable explains me, it is him, first through his presence, then his suffering, finally his departure. The irony is that his early departure lent only more permanence.

In many ways, he has been with me since he left. In the walks I take alone. In every Eid prayer. When I drink tea with muri. I keep a black and white picture of him on my office desktop. It shows him, at 38, with a mustache. For me, black and white pictures simplify memories. My office cleaner, Sukunti, once nervously advised, "If you are going to keep your own picture on the table, please get a different one in colour but without the mustache." My father and I look a lot alike.

A few months after he departed, I left for the US. The next two decades, my 20s and 30s, flew by in schools, in jobs. Of and on, I would replay the 1980s in my head, picture that krishnachura in the Mirpur cemetery. American writer Graham Greene once said life is lived in the first 20 years and the remainder is just reflection. He seems almost right.

Then happened Cambodia. I read up on the politics, the history, and the old IMF reports for the job interview but knew little about the society beyond the genocide and Angkor Wat. It was only after I moved that so many memories unfurled, swirling in a time warp.

The familiarity was disorienting: the krishnachuras; the palm trees; the oxcarts; the dheki for husking rice; the new year on Pahela Baisakh; the sound of heavy rains; the alphabets - ka, kha, ga, gha - and faces blending Indo-Chinese features. Phnom Penh partly resembled a reincarnated 1980s Dhaka; rural Cambodia perhaps a muffled echo of the Buddhist Bengal. The initial surprise borne out of my own ignorance slowly matured to gratitude.

In one of the worst mass killings of the 20th century, Cambodia lost three million of its seven million people during the Pol Pot years, 1975-1979, leaving no one unscathed. In my office, Yong, the driver, lost his grandfather; Sukunti, the cleaner, her father; Chenda, the assistant, her brother; Leapho, the manger, went to look for food for his starving family, only to find upon return that they were all killed. Their smiling faces gracefully masked souls full of crater-like losses, dwarfing mine, making me, for the first time, even thankful for my father's natural departure. For the short five years in hospital.

The chemistry of memory is complex. The hippocampus and the frontal cortex areas in our brain store memories, which can erupt, mutate, and even nest like onions in layers as we reinterpret our past and experience the new. Memories also decay with time, that's how we eventually forget something. For me, the krishnachuras halted that decay, provided a refuge for my memories, perhaps replenishing my frontal cortex.

Looking back, I wonder if the powerful resonance I felt in Cambodia had more to do with the phase of life I was about to enter. In our forties, like a half-moon, with more yesterdays than tomorrows, we are aware of transitions: the shrinking world of my mother from dementia making space for the expanding universe of my 3-year old. Like the impossible staircase in an Escher painting, 40 is where the beginning and the end intersect, the past and the future merge.

1991-2015. Last August, I moved back to Dhaka, as a friend once said in jest, in response to my mid-life crisis. A week after I arrived, I visited my old elementary school. The library and the playground now look much smaller than I recall. Although I struggle with the ghosts of my memories, my daughter is relishing Dhaka with fresh curiosity, unburdened by any nostalgia to create her own memories.

Slowly, I am learning to not resist the obvious - Dhaka is no longer the city that I grew up in. Dhaka has moved on. Now with crowded roads, shopping malls, cell phones, 24 hour TV channels and modern ads, shrinking lakes, fewer trees, traffic jam, and fast food joints on every corner, the society sits atop the fluid vortices of change. Amid aspirations, the rise of the market, growing strains and affluence of many with their busy lives, social values and norms in flux. The collision of my out-of-focus memory with the present was inevitable.

Around the time I started feeling settled in, on March 7, a news caught my eyes: artist Khalid Mahmood faced a tragic death as a krishnachura fell on his rickshaw in Dhanmondi. In a surreal coincidence, a year ago, he had an art exhibit in Chicago titled Krishnachura: Poetry of Color.

In Cambodia, krishnachuras triggered memories of my father, of 1980s Dhaka. Now, in Dhaka, it ignites my reminiscing Bangladesh in Cambodia. After March 7, it also reminds me of Khalid Mahmood, whom I never met.

On my father's death anniversary this year, March 25, I went to Mirpur with my daughter. The krishnachura and the pond are long gone to make room for new graves. My daughter, now 7, will have no memories of the krishnachura but will inherit and perhaps curate the stories of my memories. As we were walking back from his grave to the car, she held my hand tight, asked where the pond was.

In endless cycles, we keep growing as do our memories, even, or especially, that of a krishnachura near a pond in a cemetery.

The writer is a macroeconomist.

Email: faisalxahmed@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments