How education and stimulation in early years can help children thrive for a lifetime

Today, 99 percent of Bangladesh's girls and 97 percent of boys are enrolled in primary school. The great progress in primary education over recent years is the reason that the country has met the two Millennium Development Goals related to primary schooling: universal enrollment and gender equality.

The rest of the education story, however, is not so good. Concerns remain over poor education quality, and enrollment rates beyond the primary level remain low. And one important concern for education is something that appears rather separate: stunting, or the condition of being shorter than normal for one's age. It matters, because it holds back learning and development.

Investment in education holds promise to help move Bangladesh closer to the goals of Vision 2021 and beyond. What are the best ways to address the issues faced by the country's education system?

New research by economist Atonu Rabbani of the University of Dhaka suggests that there are several worthwhile strategies that could improve public education in Bangladesh. One is most promising of all: so-called psychosocial stimulation to help young children overcome stunting.

Six million Bangladeshi children, including 40 percent of kids under 5 years old, are stunted. It can be caused by inadequate nutrition or repeated infections during a child's first three years. The effects often last a lifetime: delayed cognitive development, lower productivity, poor health, and increased risk of certain diseases.

And the importance of early childhood development is crucial: Studies show that early development means higher intellectual achievement later in life, higher future income, and less criminal activities. It can even lead to better health outcomes.

Fortunately, there's solid evidence for a strategy that can help stunted children overcome their early-life setbacks entirely and allow them to become just as healthy and productive later in life as their peers.

The analysis examined a project that was launched in 1986 in Jamaica. At the beginning of the study, stunted children between age 9-24 months lagged behind in both learning and productivity compared to non-stunted kids. During the course of the programme, stunted children were visited weekly by education social workers, who led play sessions to develop cognitive, language, and psychosocial skills. The visits lasted for two years, and the social workers also taught the mothers of the children how to do the same stimulating activities with their children, so the effort lasted beyond the workers' end date.

The results of the long-term study in Jamaica could hardly be believed - the psychosocial activities had negated all the deleterious effects of stunting. After 20 years, the children in the programme had completely made up the gap to their non-stunted peers, as demonstrated by their equal wage and earnings levels. Stunted children who were not part of the programme, however, earned 25 percent less than the wages of the treated and non-stunted groups.

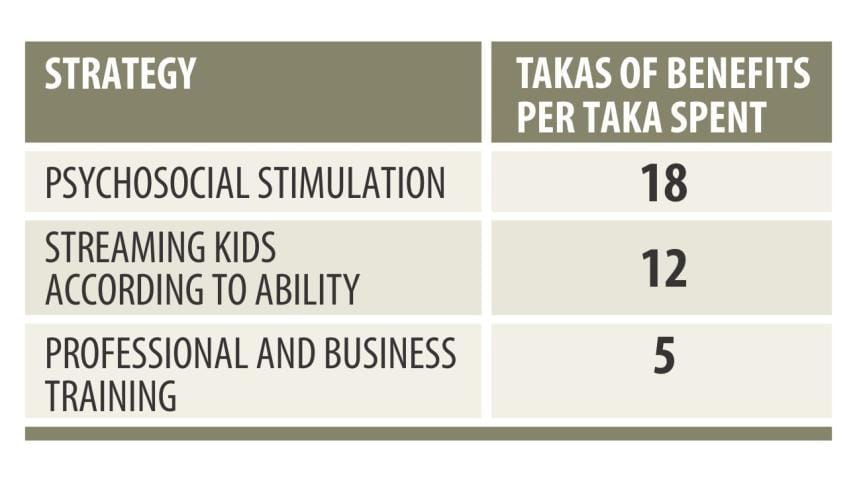

When translated to Bangladesh, the cost of such a programme is one hour per week for a social worker for each child, which would equal Tk.12, 450 per child each year. And the benefits turn out to be incredible. An estimated wage increase of nearly 20 percent is worth more than Tk. 1.5 million (Tk. 15 lakh) for each child over their working career. Each taka spent on psychosocial stimulation programmes for early education of children would do Tk. 18 of benefits.

The benefits from the stimulation programme were most promising, but other strategies that the research examined held promise to do good as well.

Among the various programmes studied, "streaming," or reassigning students into groups according to their levels of educational attainment, has shown promise to increase student achievement in a cost-effective manner. The experts conservatively estimate that in Bangladesh, every Tk. 7,800 spent on reassigning students according to their achievement levels could increase student test scores by nearly two standard deviations, which is correlated with earning higher future wages. The money would be spent throughout the five years of primary schooling and could also allow for hiring more teachers. Each taka spent toward these efforts would do about Tk. 12 of good.

On-the-job training for managers also appears to be a decent idea. It can help increase firm productivity and the wellbeing of employees, especially in sectors like the readymade garment industry, where schooling levels are actually lower for many new supervisors and managers. The return on investment in professional training would come from increased worker productivity. It may not be as large as human capital investment in early childhood, but it may be more in line with firms' incentives. Each taka spent on this sort of training would do Tk. 5 of good. A remaining challenge, however, is that there are still social norms that prevent women from achieving management roles, which hinders progress for many and contributes to lower productivity.

What do you think? Is investing in schooling, and in early childhood education in particular, the best way forward for Bangladesh? Earlier, we saw how improving migration opportunities could provide benefits. Where would you choose to spend money if you were in charge and wanted to do the most good for the country? Let us hear from you at https://copenhagen.fbapp.io/education. We want to continue the conversation about how Bangladesh can do the most good for every taka spent.

The writer is president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, ranking the smartest solutions to the world's biggest problems by cost-benefit. He was ranked one of the world's 100 most influential people by Time magazine.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments