A war-cry for sustainable development goals

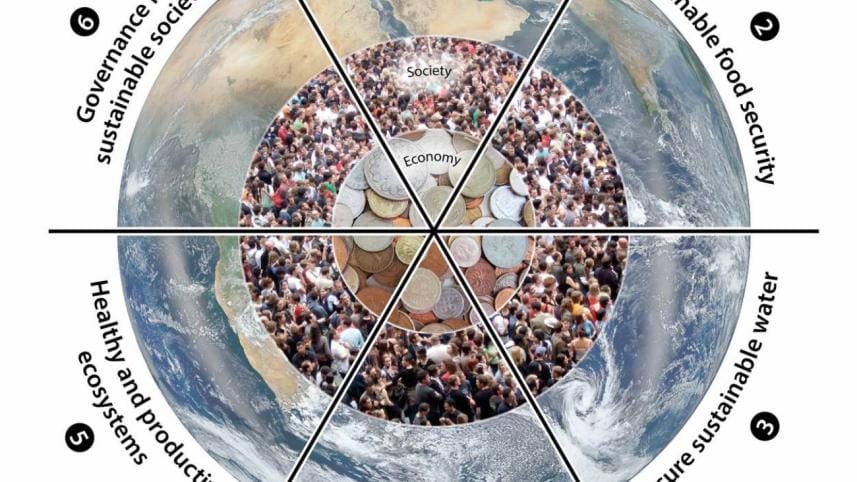

During the 1992 presidential campaign in the USA, candidate Bill Clinton's campaign adopted a very powerful short message to convey to the party faithfuls and voters that the poor performance of the US economy should be the centerpiece of any conversation to unseat the incumbent President George Bush. Thus the slogan, "It's the economy, stupid!" became the rallying cry that led to the victory of Clinton over Bush. A powerful phrase can often galvanise the forces of change and also keep the focus of any national or international movement on target. Unfortunately, world leaders who gathered at month's UN "Financing for Development" (FFD) conference in Addis Ababa failed to agree on a common platform to raise funds, and left up in the air for future meetings any financing mechanism for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) programme. As the group deliberates over the next few weeks before they launch the SDG in September, it may not be too far-fetched to ask them to embrace "poverty eradication" as the most important goal for humanity in the coming decades, and put strategies to eliminate poverty at the forefront of their discussions and negotiations.

Why bring up the long-discussed mantra of poverty elimination once again as we struggle with many other important issues that are currently plaguing the world? First of all, even as the world media and political leaders grapple with the Greek crisis, climate change, and sluggish growth in the world economy, let us not forget that it is the poor of the developing countries who bear the brunt of the world's most persistent and dehumanising calamity of all - poverty. Secondly, as many Least Developed Countries, including Bangladesh celebrate the achievement of Middle Income status (or Lower Middle Income status), it cannot be gainsaid that the status of the poor and extremely poor remains the same: hunger, deprivation, and constant economic and physical struggle. Thirdly, the fight against poverty should be a never-ending battle. We can pull one poverty-stricken family out of poverty, but if another family takes its place in the queue, we need to keep working and nothing else should get us distracted.

In this context, it is heartening to note that the summit at Addis Ababa, capital of Ethiopia, will be attended by United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon and World Bank's President, Jim Yong Kim. However, only eighteen heads of state, mostly from developing countries, will be participating at the meeting which is supposed to lay down the groundwork to launch the SDG in September but most importantly, seek ways to raise $172.5tn over the 15-year timeframe needed to finance the seventeen targets. And then, there is the question of priorities among the developing as well as developed countries. There are many competing and divergent goals: poverty elimination, environment, gender equality, and social inclusion. One can only hope that during the discussion on the means to finance the seventeen goals, the participants will address the challenge of getting the most bang for the buck in terms of poverty reduction. After all, if $172.5 trillion cannot meaningfully eliminate poverty, or even extreme poverty within the 15-year framework, i.e. by 2030, the ghost of another US Presidential slogan from 1984 ("Where's the beef") might come back to haunt the rest of the world.

As the august gathering in Addis debate the sources of funding the programme, a word or two about measurement of poverty and the "Middle Income Country" label might not be out of order here. When we celebrate following the success of any poverty-elimination programme, we need to ask: "How do we measure poverty?" Whether we take $2 or $4 as the threshold, official or statistical measures can give very different answers depending on how we count and whom we count. I will just offer a simple example that I often use to convey to my students how statistical measures can be deceptive. Suppose, the population of Portlandia is five, and they each earn $1 a year, in 2014. The per capita income of Portlandia is $1, and if the poverty limit is $2, we have a 100 percent poverty rate. In the following year, one of the five increases his earnings to $10 and the rest of the population stay at $1. The per capita income jumps to $2.8 in 2015 and the poverty rate decreases to 0. But as we can see, the majority of the population of Portlandia remains poor. Let us take another example. If in the year 2016, incomes of three workers drop to 50 cents each, but the incomes of the two others are 3.5 and 6. Per capita income is $2.1 but the poverty rate is still 0. In fact, the number of poor has dropped from 2015 to 2016, but the three who now eke out a living at 50 cents, have become extremely poor. What's the moral of this story? One needs to very carefully select the statistical measure, and be aware of its limitation, when we count the poor.

Finally, as Bangladesh and a few other countries move up the ladder and attain Lower Middle Income Country status, how does this affect the poor? Not much, according to a new study by the prestigious Pew Research Center, a global think-tank based in the USA. As our average income crosses the $1,045 threshold, this growth in income could be consistent with a worsening of income equality and increase in the number of poor, or even the poverty gap. The study uses the $2 poverty line. This is done in anticipation of the change of World Bank's global standard for extreme poverty, now at $1.25, which is expected to move close to $2 when it incorporates 2011 purchasing power parities (PPP), rather than the 2005 PPP currently in use.

While I am not advocating that negotiations over SDG goals and financing focus exclusively on eliminating poverty, it provides a great opportunity to realign our direction and reaffirm our commitment to the betterment of the condition of the poorest segment of the world's population.

The writer is an economist who writes on international economic and policy issues.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments