Young voters poised to shape next election

They grew up hearing that voting was their right, only to watch how easily that right could be snatched away in elections widely criticised as “sham polls”.

Unlike the last three elections, the conditions are different now.

Bangladesh’s young voters are stepping into an election shaped by uprising, reforms, and the promise that their ballots will finally carry weight.

Nearly half of the electorate is now eligible to cast ballots, emerging as what experts describe is a decisive force in the country’s democratic transition.

Aysha Tofail, a final-year student of mass communication and journalism at Dhaka University, feels that the upcoming election has made her reflect on her role as a citizen. In her words, “Voting is often described as a civic duty, but for young people like me, the decision to vote or not is shaped by hope, and lived reality.”

“On one hand, I want to vote because it is one of the direct ways I can participate in shaping my country’s future. As a student, I worry about employment opportunities, education quality, and the rising cost of living.

“Casting a vote makes me feel that my voice, however small, matters. We signal that we care about governance, accountability, and the direction Bangladesh is heading,” she said.

“I believe voting has value. Even if the system is imperfect, choosing not to participate only weakens the influence of young voices further.”

Her sentiments resonate far beyond campus walls as crores of young voters are preparing to go to the polls, say election experts, including Electoral Reform Commission Chair Badiul Alam Majumdar.

Besides the national election scheduled for February 12, 2026, their choice could also shape the outcome of a referendum on constitutional matters under the July charter, born of the recent mass uprising.

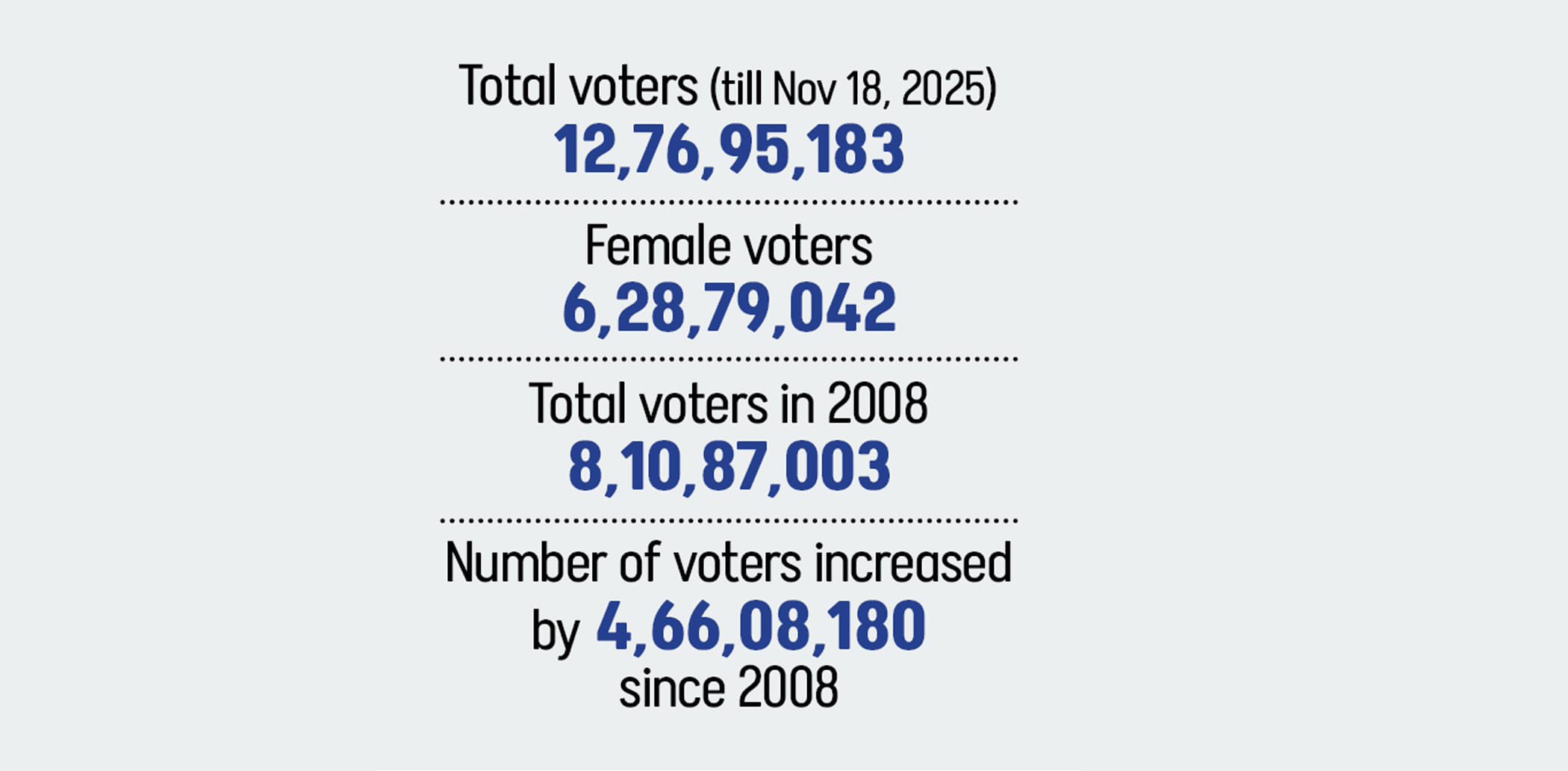

The numbers tell a story of scale. In the 2008 election, Bangladesh had 8,10,87,003 registered voters. By November 18, 2025, that figure had grown to 12,76,95,183, including 6,28,79,042 women -- an increase of 4,66,08,180 voters over 17 years.

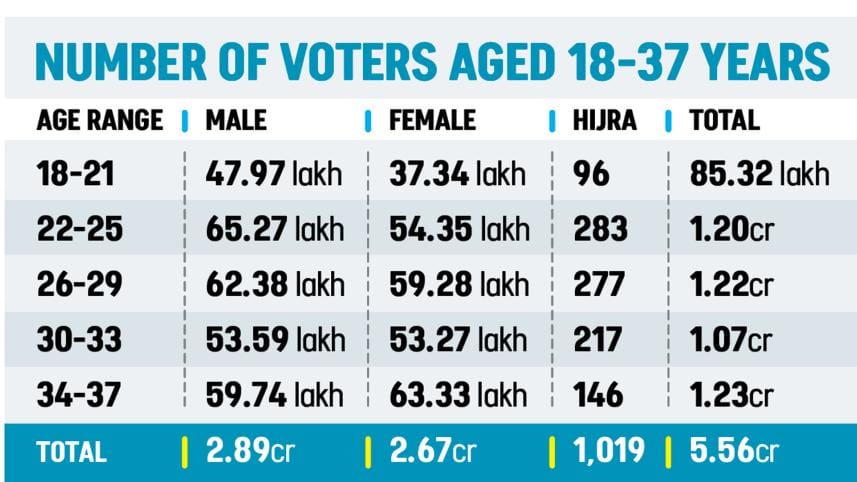

Election Commission data show that as of January 5, 2026, some 5,56,53,176 voters are aged between 18 and 37, accounting for 43.56 percent of the electorate. While definitions of “youth” vary internationally, Bangladesh’s National Youth Policy 2017 classifies those aged 18-35 as young.

“And this huge percentage is a major factor. Because in Bangladesh, whenever you see a truly competitive election between two parties, with fierce rivalry, you’ll notice that sometimes a candidate wins by just a few hundred votes, sometimes even fewer,” said election analyst Abdul Alim.

“Whichever side the majority of these young voters support, that candidate’s chances of winning will be significantly higher,” he added.

Both Alim and Majumdar noted that many new voters were effectively denied ballots in the past three disputed elections. “Many tried to vote but were unable to,” Majumdar said.

“They are a decisive factor in the national election to be held on February 12. For a referendum, they would be an even greater deciding factor,” said Majumdar, who is also secretary of Shushashoner Jonno Nagorik.

The political backdrop has sharpened these stakes. In July 2024, a youth-led uprising culminated in regime change the following month and the installation of an interim government. Although elections are typically held every five years, the upcoming polls came just two years after the January 2024 vote, following the ouster of the Sheikh Hasina government.

Most of these young voters, Majumdar said, were not mere observers. “Many of them witnessed their friends and acquaintancessacrifice their lives or suffer injuries. So it is a very sensitive issue for them.”

“They took to the streets for the vision of creating a new Bangladesh. This movement is captured by three priorities: one is election, another is reform, and the third is justice.”

EAGERLY WAITING

That urgency is reflected in surveys. The Bangladesh Youth Leadership Centre’s Youth Matters Survey 2025, released in mid-December and based on responses from 2,545 people aged 18–35, found that 97 percent intend to vote.

Asked to name priorities for the next five years, 67 percent cited eliminating corruption, 56 percent addressing unemployment, 24 percent safety and security, and 14 percent the protection of democratic rights.

A separate poll by the US-based International Republican Institute, conducted among 4,985 respondents -- including 2,518 youths -- and released in early December, found that 89 percent were likely or somewhat likely to vote. While 80 percent expressed optimism that the upcoming polls would be free and fair, 67 percent said past elections had been rigged.

Abdul Alim said the frustration of being excluded before has turned many young voters into first-timers determined to participate. “That’s why they are eager to vote. They will go to the polling centres,” he said.

SCARS OF PAST POLLS

Those memories are not abstract. The January 5, 2014 election was boycotted by the BNP and other opposition parties after their demand for a nonpartisan caretaker government was rejected. As a result, 153 MPs were elected unopposed, and turnout stood at 40.04 percent.

The opposition returned to the fray in December 2018, but the vote was marred by allegations of overnight ballot-box stuffing. Opposition parties claimed that 30 to 60 percent of votes had been cast before polling day. A study by Transparency International Bangladesh found evidence of such practices in 33 of the 50 constituencies it surveyed. Official turnout was reported at 80 percent.

In the January 7, 2024 election, turnout fell to 41.80 percent as opposition parties again stayed away, refusing to contest polls held under Hasina’s leadership. The ruling Awami League fielded independents -- widely labelled “dummy candidates” -- to maintain the appearance of competition.

For many young voters, these episodes remain fresh in memory. Some were prevented outright from voting; others faced intimidation at polling centres. Many ultimately chose not to cast a ballot.

Adnan Ahmed, a private service holder who first became a voter in 2018, recalls his experience clearly. After verification, he was given a voter serial number, beneath which an instruction was written: “Vote for Boat”.

“When I proceeded to the voting booth, I found the so-called ‘secret chamber’ wasn’t that secret. The booth was completely open, with several Chhatra League goons standing around it,” he said.

“They were watching everyone cast their votes and instructing them to ‘stamp on the Boat.’ Intimidated, many were complying.”

Adnan objected.

“I asked, ‘Who are you? This is supposed to be a secret booth with screens around it. Why are you breaching our privacy?’”

The confrontation escalated, and the men were on the verge of attacking him before a colleague of his father, serving as a polling officer, stepped in.

Disillusioned, Adnan stayed away from the January 2024 polls.

In all three elections, the Awami League-led alliance went on to secure two-thirds majorities.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments