Why we must rethink how we think about the future

When we try to envision, conceive, and plan for our priorities for tomorrow, we inevitably, and often unwillingly, submit ourselves to the concept and implications of the dominant paradigm of temporality in our lives. Unfortunately, the complex and varied intertwinement of time and lived experiences is hardly addressed in discussions of public space and policymaking. The idea and practice of defining ‘priorities for the future’ are an essential aspect of the inherent normativity and psychopolitical repertoires of the neoliberal state. The past is, explicitly or implicitly, present in these desires, hopes, and dreams for a future. Often, the past is imagined as a homogeneous, linear, and uniform glorified existence of the human experience, which has continuously been lost, polluted, and derailed. I want to focus on this complex history of temporalities and the formation of the neoliberal unconscious urge for the future. In this assumption, the human species is the central actor with full control over the future. This anthropocentric perception of temporality is one of the key problems in perceiving a planetary-scale time and future for all human and non-human actors.

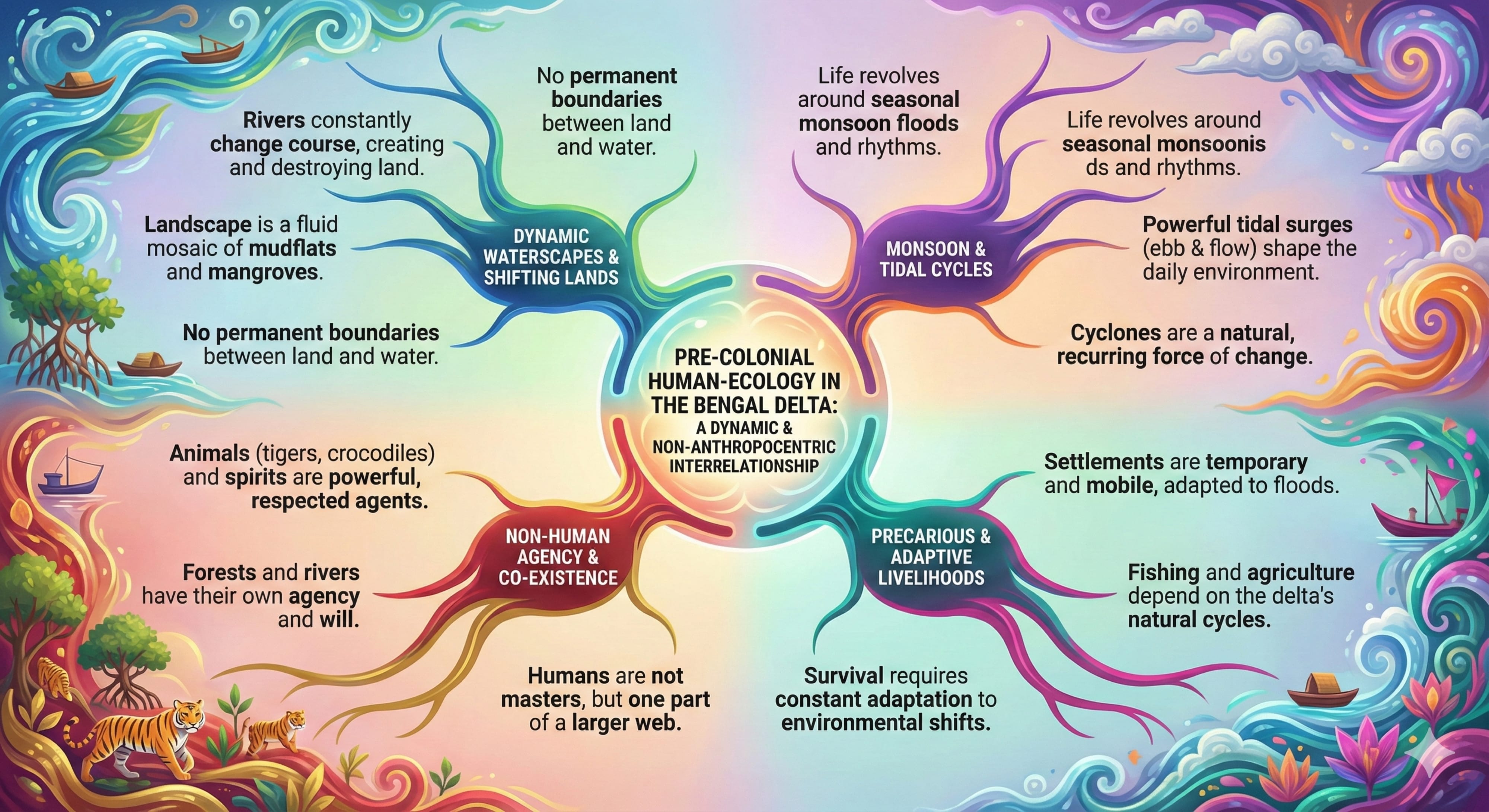

I am not claiming that human actors are not the most dominant species on the Earth, either as a planet or on a smaller scale, such as in the Bengal Delta, which serves as a cultural, political, and ecological territory. Rather, the idea that we can analyse, assume, and plan for the future is founded on the broader anthropocentric paradigm of modern neoliberal doctrines. Time here is linear, progressive, and its speed and direction can be controlled and manipulated in a certain way to ensure authoritarian and totalitarian superiority in ensuring prosperity, development, and stability. I find all the ideas and methods of anticipating a controlled, dominant, and prosperity-centric future very problematic. Essentially, cruelty, hatred, violence, narcissism, and genocidal fascist and totalitarian identity politics are entangled with the human assumption and desire to predict, refashion, and model according to their own worldview and intention.

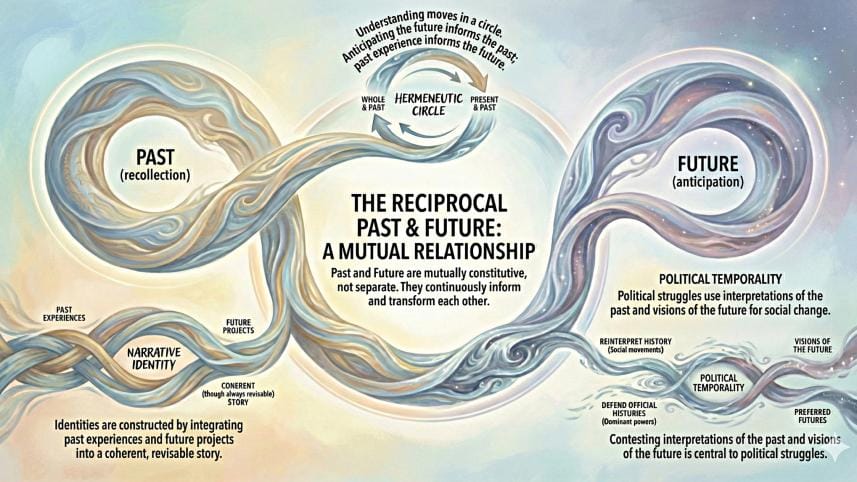

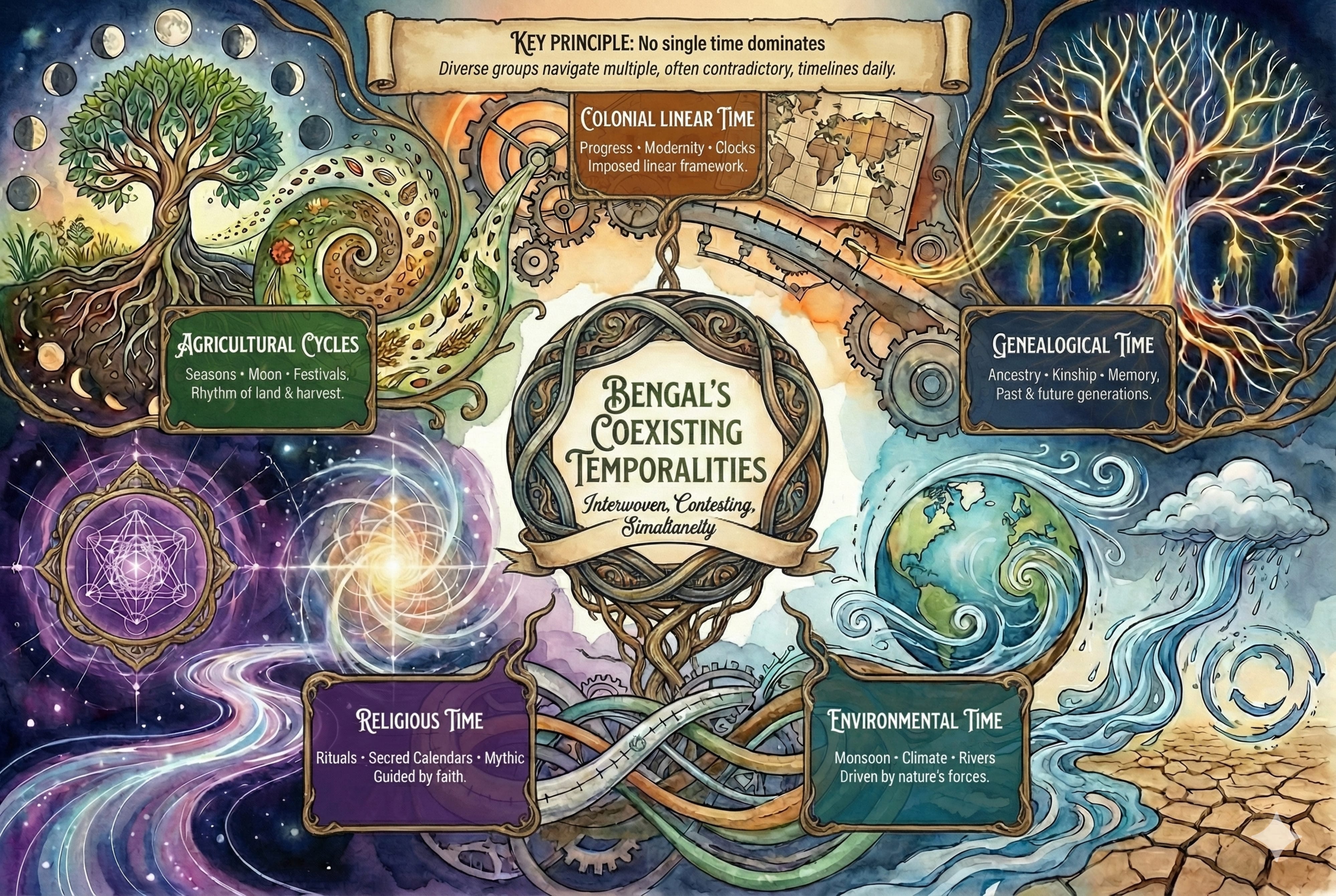

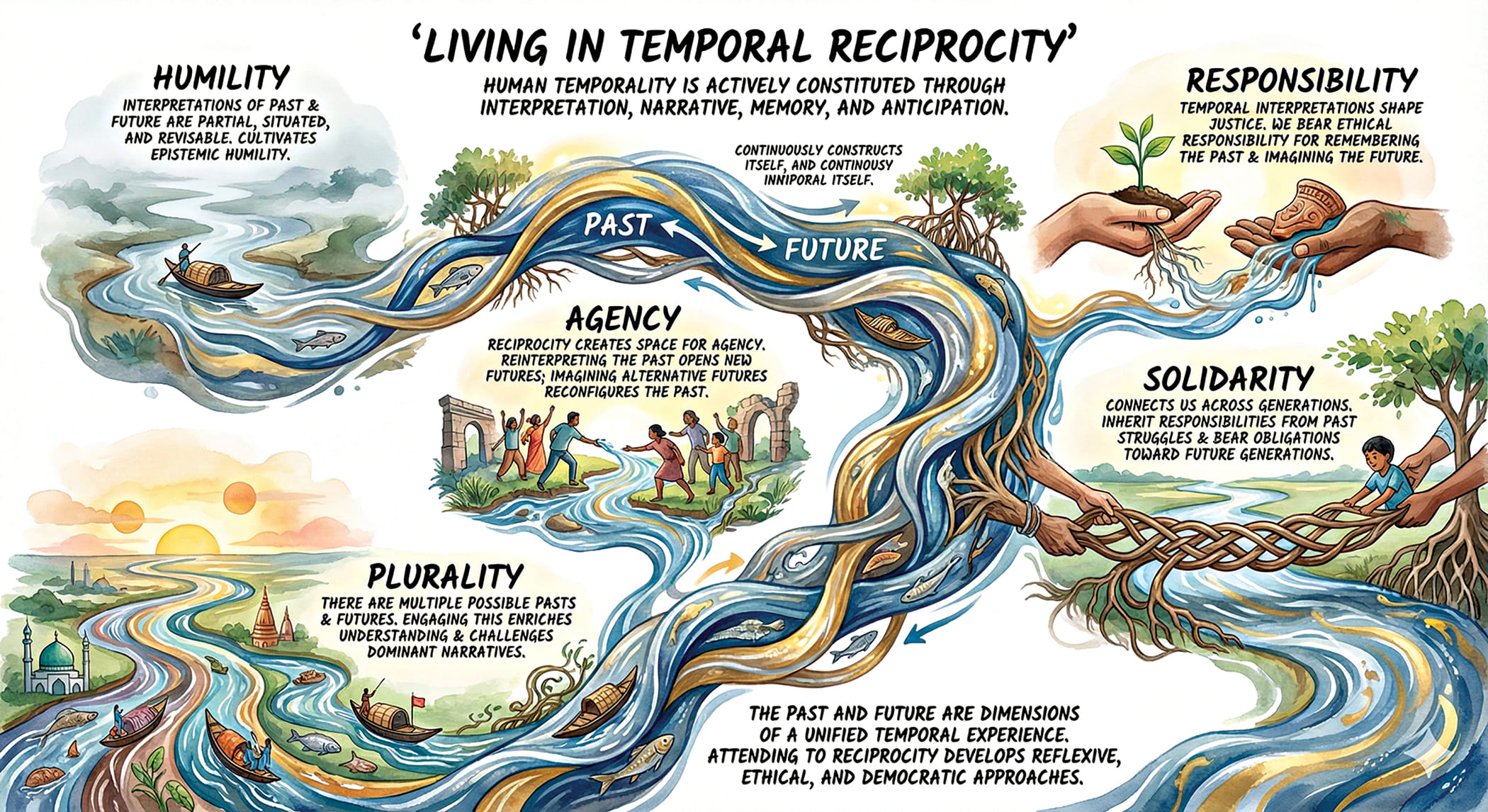

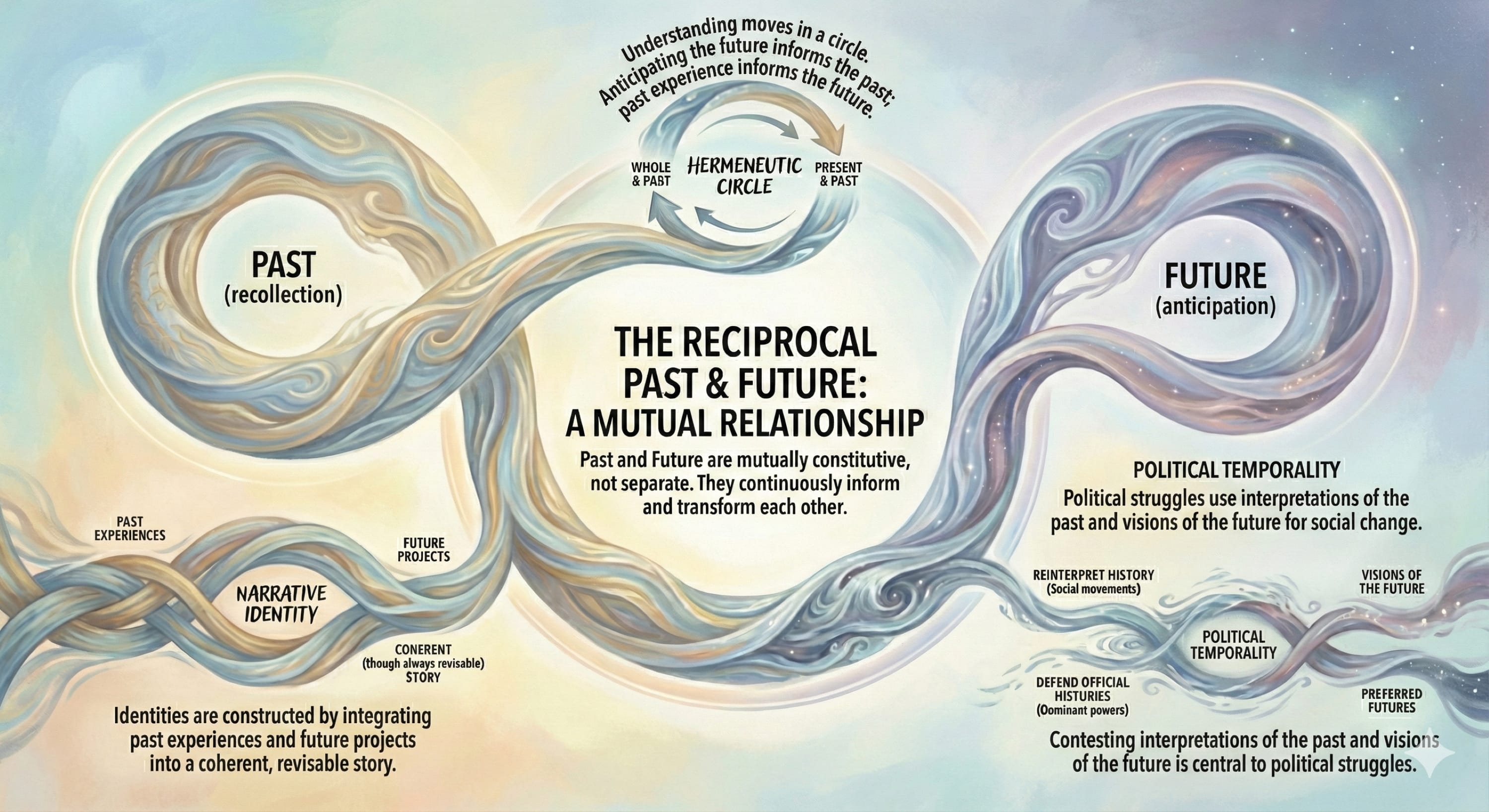

On the one hand, a neoliberal psychopolitical dimension must be taken into account. Thinkers such as Byung-Chul Han have highlighted many of the conditions and effects of temporalities, as well as the practices in various institutions, including the nation-state and multinational corporations, and the political and psychological formations of our sensibilities and agencies, in his works. We have internalised and been consumed by the notion that nothing is impossible, and we are free to control our future and time. On the contrary, the growing digital ecosystem, neoliberal system of corporeal existence, and flexible forms of capitalist world have enslaved us with the delusion of freedom and autonomous agentive action of the human species. On the other hand, the homogenisation, uniformitarianism, and universalisation of linear time and calendars have rendered invisible the multiplicities of different temporalities, sensibilities, perceptions, and practices in various societies, cultures, and spaces. In many cases, time is not perceived as a continuum from the past to the future. What is recognised as future and past are not simply separate periods or phases of linear and abstract progressive time. Rather, the past and future mutually constitute each other. They are neither fixed nor do they exist in the tripartite scheme of past, present, and future. In many cultures and practices, human and non-human species are considered as aspects of deep, fluid, and uncertain temporalities, and human actions and desires to control and dominate time, future, and space (e.g., the Bengal Delta) are shaped and fashioned with regard to a fixed utopia of a prosperous, more profitable, and more human-controlled future. These perceptions and practices are futile and bring to the fore the current global paranoia about identity and the fear of the extinction of various entities on planet Earth.

Let us ask who counts as a legitimate member of a political community who has the right and capacity to interpret the present and determine what the desired, expected, and anticipated are as the `priorities for tomorrow’? What kind of present needs and future orientations are refashioned (and identified as illegitimate and invalid)? How are these legitimisation and illegitimisation of the priorities in the future reconfigured and normalised through ideas of the past, narratives, memory practices, and historical frameworks? What kind of narratives are generated and circulated (and what kind of narratives are cancelled and delegitimised) for producing meaningful living and its anticipation? How have these anticipations inherited structures, categories, and constraints from past experiences and collective memories? How have we dissociated the discourses and ethical sensitivities in Bangladesh for foreclosing or enabling possibilities for the future?

In these senses, even making sense of the possibilities in the future is intertwined with the ways in which memories, narratives, and practices are celebrated, accepted, or rejected at the present, and this is an ethical and political act. In the dominating cultural and political discourses in Bangladesh, we may identify the selective and cherry-picked events and narratives of the past that are used to memorialise and celebrate. We construct a sensibility of eternal and unchanging victimhood and heroism in validating the priorities of the future. The foundational causalities and contingencies of how the past and future mutually constitute each other are hardly discussed and debated.

At this moment of clashes of various identities and the production of hatred, cruelty, greed, torture, pain, and violence are validated in reference to both retropia and utopia. A sacred, primordial, original, and idealised past is anachronistically invoked for a sacralised, emancipatory, and hopeful future. The intense hatred and annihilating violence we are experiencing are different from the earlier contexts and casualties in various ways. The cruelty is not simply an act of vengeance and sacralisation aimed at removing the pollution. The torture, infliction of pain upon the other, and violent outbursts at the collective scale are formed by the chronic and accelerating information flow in the digital universe to consume, record, and circulate the visuals. This is a new condition. Through the circulation and acceleration of the information, the pathology of the controllable and anticipated future is validated, and the line between truth and falsehood is obliterated. This is a state of continuous and perpetual inhabitation within a world of erasing present inferiority and pollution, with the prioritisation of the original and primordial retrogression. Ethical living, which ensures justice and freedom, has led to the changing and inconsistent invocation, as well as the narratological acceptance and rejection. The actors who control the future through the actions of controlling the past are forgotten, trivialised, and rendered invisible.

If we focus on the priorities for the future’ regarding the varied, heterogeneous, and differential existence of all species and sentient beings in the Bengal Delta (and present-day Bangladesh), the bleak and dystopian future cannot be concealed by all the discursive imaginaries. Climate change and the global impacts of human exploitation and interventions on a planetary scale cannot simply be reduced to the local scale. Simultaneously, the local cannot always be extended and connected to the global. Global and local are mutually constitutive and connected. The invocation of any civilisational uniqueness’ in terms of the retrospective thrust of a victimised past, as we can find in many popular discussions in the public space, is constructed to cancel the critical and conceptual engagement with the complexities and contingencies of the mutual connection of space and time.

Neither the programme to search and reenact selective appropriation of something indigenous’ or originally of the soil’, nor the pressure of connecting to the progressive flow’ of the world, is going to help us out of the current helplessness and anticipated hopelessness or the state of the coming age of existential closure. Considering the intensity, number, and exponential rise of violence, suicide, murder, torture, and the erosion of tolerance and empathy in Bangladesh, all the discourses and realities of legitimisation and delegitimisation, all the practices of erasing the boundary between truth and post-truth must be subjected to intense epistemological, political, and sensitive examination, self-reflection, and introspection. The increasing identification of agency in terms of a singularised subject - I’ - has to be replaced by a continuously dialogical and interactive subject - we’. This we’ is not simply the privileged, elite, and powerful human agents and actors, but also the non-human entities of the delta: the rivers, water, rain, soil, vegetation, animals, forests, grasses, clouds, and oceans within the limit of the cartographic territory of our motherland, as well as the supra-territorial existence of all the living and non-living beings.

What we are noticing in the name of a sustainable future and sustainable development (instead of an inhabitable future), or in the plan for delta management, or environmental and biodiversity protection, has failed to recognise and accept this notion and identity of `we’. All these plans and actions (at least those on paper) have not paid adequate attention to the multiplicities of our being and becoming in heterogeneous pluriverse connections, nor the changing connections among temporalities, existence, inhabitability, and empathy. We are facing doom; people are not getting fresh drinking water in the expansive coastal regions; every year the frequency and intensity of flash floods is accelerating; the forest and hills are being consumed in the name of human living and development; wetlands and rivers are grabbed, embanked, controlled, or managed to promote a spectacle of sustainable developmentalism; groundwaters are depleting due to overexploitation for irrigation; hybrid species have colonised the entire ecosystem, and with the false propaganda of ensuring a better future and economic gains, the land and water interconnection is severed and destroyed.

Under these circumstances of ordinary living and experiences, the social media narratives of cancel culture and identity politics have normalised cruelty, infliction of pain, and violence as a normal and necessary evil. We have failed to explore the political psychology of everyday life in the blurred territorialities of the virtual and the real. A simple recognition of hatred and cruelty towards the non-human entities is absent in any discussions by the policymakers and intellectual activities in the urban elitist hubs. Before discussing the priorities of the future, we must therefore recognise the dignified living and survival of every entity in our country and in other parts of the world as well. We must unlearn and recognise our mistakes, failures, and inadequacies in engaging with the multiplicities and differences; we must reflect upon the past without any selection or bias, and agree to live our lives in intimate and empathic relations with others, both human and non-human.

The act of recognition and acceptance is the priority for me, the transformation from a selfish, narcissistic, and delusional I’, from a future greedy, achievement-centric, and competitive subject - I’ - to a multitemporal, trans-species, and empathic `us’ inhabiting the fluid and mutually constitutive past-present-future is my hope to live with dignity, freedom, democratic, non-authoritarian conditions on the temporal flows.

Key Points

1. Neoliberal futures in Bangladesh assume linear, controllable time and human dominance.

2. The past and future are mutually constitutive, shaping perceptions, narratives, priorities.

3. Anthropocentric planning ignores non-human and ecological temporalities of the Bengal Delta.

4. Violence, exploitation, and climate impacts reveal failures of current development and governance.

5. Ethical, empathic, multispecies recognition is essential for a dignified, sustainable future.

Dr. Swadhin Sen is a professor in the Department of Archaeology at Jahangirnagar University.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.