Before the selfie age: Daddy’s self-portraits

By the time he was completing his IA, he was already twenty-four. His father realised that if his son went on to complete a BA, he would cross the age limit for employment. Given the extent of his obsession with photography and writing, his father doubted whether he would even manage to finish a BA. After weighing everything up, his father said, “Look, you are already twenty-four, soon you will be twenty-five. If you start a BA now, it will take at least another two years to pass. Once you are older, you won’t get a job. While I am still alive, take up some employment.” Golam Kasem Daddy agreed with his father.

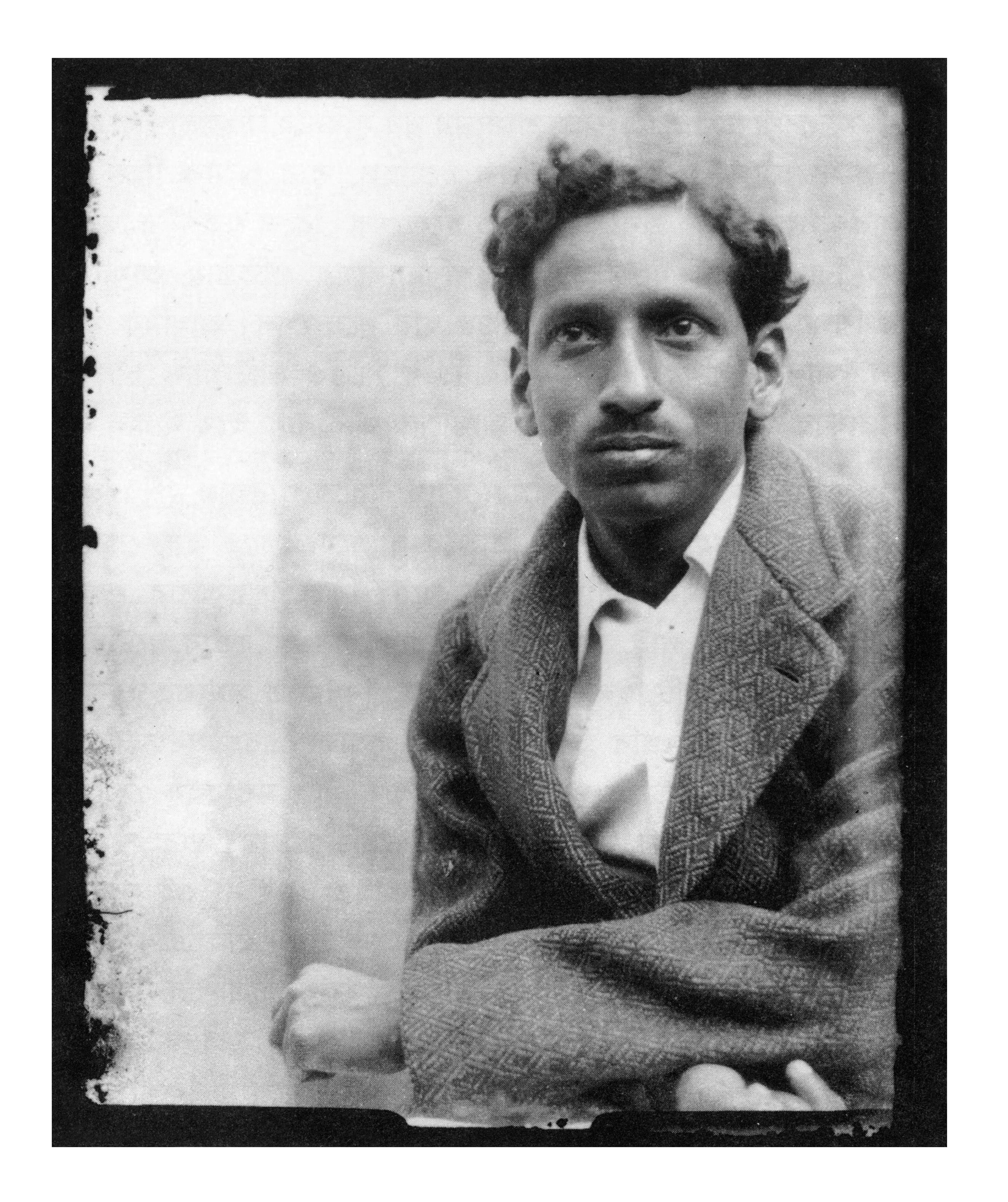

Daddy’s father, Khan Saheb Golam Rabbani, was then a police superintendent at the office of the Inspector General of Police in Calcutta. Using his connections, he arranged a job for his son as a sub-registrar. The year was 1919. The First World War had just ended. At the outset there was a six-month training period. His first posting was in Howrah, followed by Padung, and then a transfer to Bankura. He spent many years in Bankura. Of the three self-portraits of Daddy that we know today, two were taken during the early years of his service life. The first self-portrait was taken in Howrah in 1920. It is now recognised as the earliest self-portrait by a Bengali Muslim in the Indian subcontinent. For ninety years, this self-portrait remained hidden from public view. It was the distinguished portrait photographer Nasir Ali Mamun who brought it to light. In the 2011 Eid special issue of Ittefaq, he wrote a ten-page essay titled ‘পূর্ববাংলার ফটোগ্রাফি : রাজসাক্ষী গোলাম কাসেম ড্যাডি’ ( Photography in East Bengal: State Witness Golam Kasem Daddy. Daddy’s self-portrait was published on page 493 of that essay.

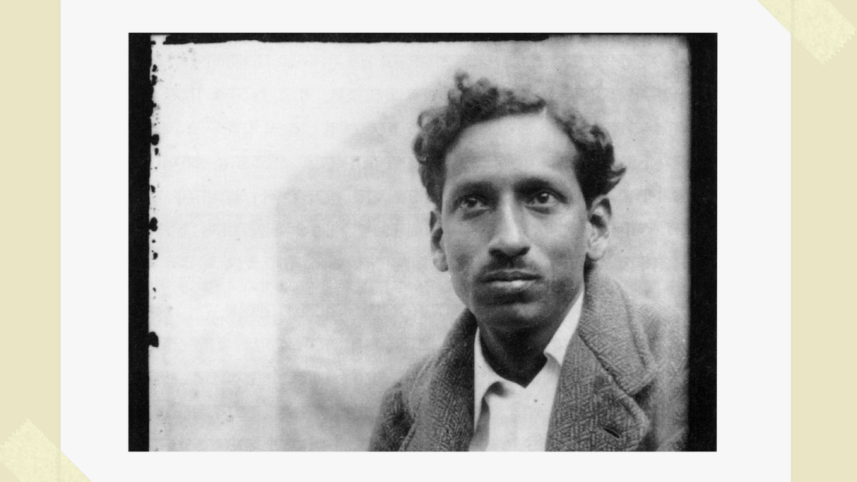

The background of the portrait is a black cloth, commonly used in those days for photographic backdrops. Daddy is wearing a coat over a white T-shirt. His gaze is not directed straight at the camera but slightly away from it, a little above the lens. There is a trace of fatigue on his face—possibly the after-effects of the prolonged malaria he suffered after returning from the war. Sitting on a stool, he took the photograph with a box camera, pressing the shutter-release cable with one hand. A portion of the upper part of the photograph has been damaged. I learned from the collector, Nasir Ali Mamun, that after remaining pressed inside paper for a long time, the emulsion on the upper part of the original negative had peeled off.

Daddy took his second self-portrait in 1922. Here again, his gaze is not directed straight at the camera. Wearing a white shirt and a black coat, he sits in a relaxed, almost leisurely pose, one hand resting on his knee. His hair is neatly parted to one side. There is a distinctly sahib-like air about him, yet his face carries a cool, restrained expression. The original negative of this self-portrait is also in Nasir Ali Mamun’s collection, acquired from Daddy in 1988 for Photoseum. At the time, Daddy told Mamun that he had not seen anyone else in Calcutta taking self-portraits. More than a hundred years on, these two self-portraits stand as some of the earliest examples of Bengali portrait photography.

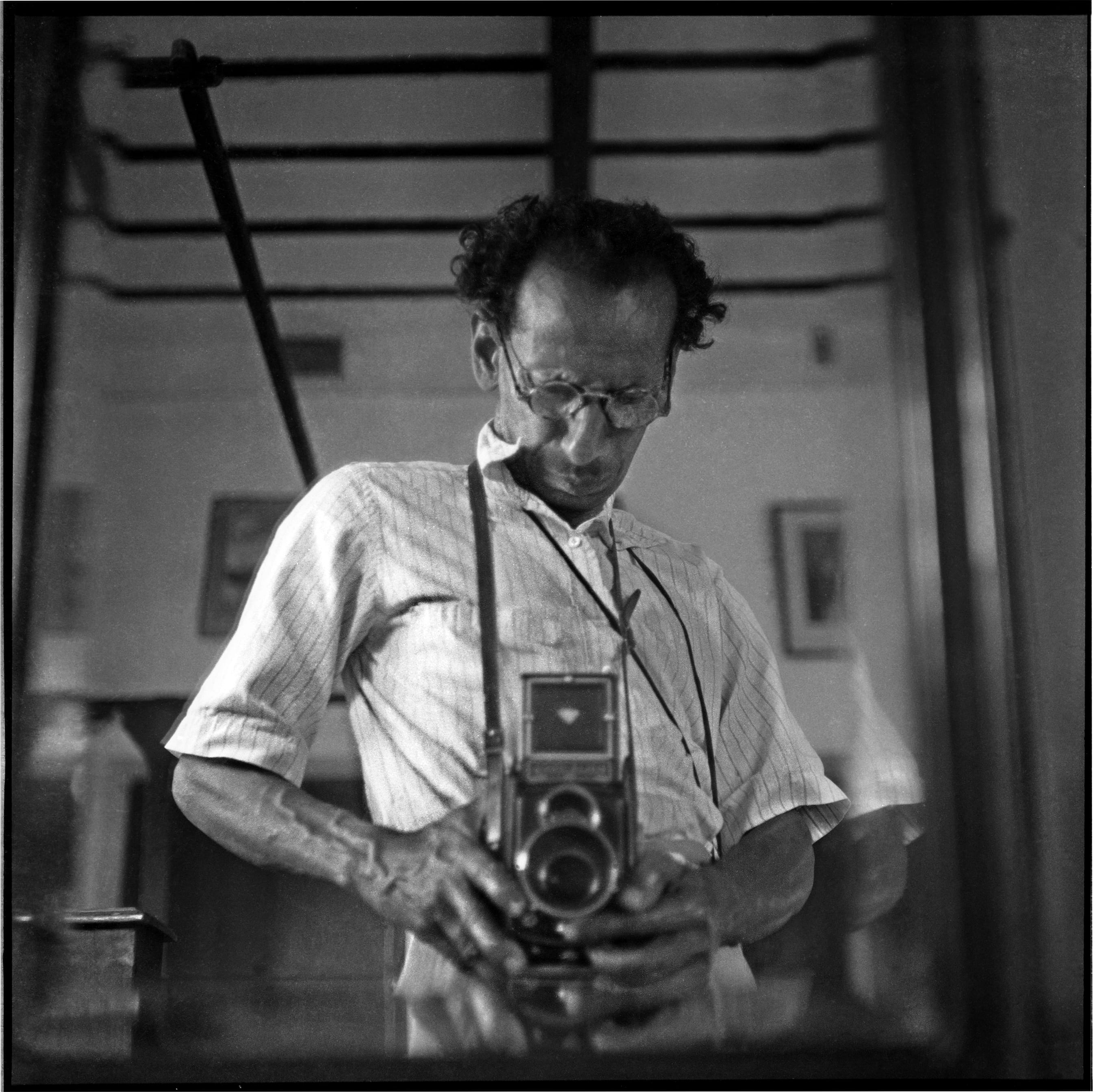

Daddy’s most widely seen self-portrait was taken in 1951. He photographed it in the bedroom of his house at 73 Indira Road, Dhaka. A medium-format twin-lens reflex camera hangs around his neck. One eye fixed on the viewfinder, he stands before a large mirror, gripping the camera firmly with both hands. As he presses the shutter-release button, the veins in his right hand bulge like the roots of a banyan tree. He was fifty-seven years old when he took this experimental photograph.

The world’s first self-portrait was taken by the Philadelphia photographer Robert Cornelius. It is believed that Cornelius made this self-portrait in 1839, just a few months after Louis Daguerre invented the camera. Wearing a black coat, Cornelius photographed his head, tousled hair, and shoulders using a box fitted with a lens and an opera glass. The Library of Congress acquired the self-portrait in 1996 and claims it to be the world’s first selfie. Daddy’s second self-portrait from 1922 bears a striking resemblance to Cornelius’s image. Cornelius died in 1893, exactly one year before Daddy was born. Whether Daddy ever saw Cornelius’s self-portrait is now impossible to know. Cornelius practised photography for only three years; Daddy remained devoted to it for more than eighty-six.

In today’s age of selfies, those who casually take photographs with mobile phones or digital cameras can hardly imagine the extent of experimentation Daddy undertook to create his self-portraits. Many may feel that the compositions of his self-portraits are simple and unadorned. Yet simplicity is the true beauty of art. He mastered this simplicity through years of disciplined practice. His photographs reveal that he himself was a simple man. Through that simplicity, he went on to create extraordinary works of art.

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.