Why the 1962 education movement must not be forgotten

On September 17, 1962, students across East Pakistan rose in a massive movement against the 'Sharif Education Policy' imposed by the Pakistan government. I was among them—not just as a participant, but as the General Secretary of the Dhaka College Students' Union. It was I who convened and presided over the very first formal gathering where students demanded the scrapping of that unjust policy and the end of discrimination in education.

In 1947–48, the number of primary schools in East Pakistan was 29,633, which came down to 26,000 within a span of five years. The Pakistan Army Chief, Ayub Khan, hatched a conspiracy with Governor-General Iskander Mirza to topple the coalition civilian government headed by Prime Minister Firoz Khan Noon. Martial law, for the first time and the first of its kind in the subcontinent, was promulgated on 7 October 1958. But within less than three weeks Iskander Mirza was removed, and Ayub Khan himself became the self-appointed President of Pakistan and Chief Martial Law Administrator.

After two months, on December 30, the government announced the formation of a committee headed by the Education Secretary of West Pakistan, and Ayub's former teacher at Aligarh University, S. M. Sharif. In the 11-member commission, four educationists were from East Pakistan: Dr Momtaj Uddin Ahmed, Vice-Chancellor of Rajshahi University; Abdul Haque, President of the Dhaka Secondary Education Board; and two teachers—Professor Atowar Rahman of Dhaka University and Dr Abdur Rashid of Dhaka Engineering College. The commission submitted its interim report on August 26, 1959.

The features of the Sharif Commission Report included:

- Urdu should be made the language of the people of Pakistan.

- English should be made compulsory from class VI.

- To introduce a lingua franca for Pakistan, a common script should be introduced and, for that, Arabic should be given priority.

- Education should not be available at minimum cost or at a cheap rate.

- There is reason to consider investment in education on a par with investment in industry.

- The concept of free compulsory primary education is utopian.

- We emphatically recommend that the two-year degree course should be upgraded to three years for improvement of quality at the higher education level.

Several of these features sparked intense agitation. Critics warned that the Commission effectively shut the door of education on the poor and low-income groups. Even the phrase 'investment in education' provoked sharp reactions. In response, committees and sub-committees sprang up spontaneously across many institutions to resist the commercialisation of education. The agitation began with students of Dhaka College and soon spread, with sporadic strikes breaking out. Students of national medical institutions also joined, some even resorting to hunger strikes."

However, the students' movement took a new turn on August 10, 1962 when a meeting of Dhaka College students announced a general strike of students throughout the province on August 15. All responded favourably to the programme. A series of meetings was held between August 15 and September 10 at the historic Amtala on the Dhaka University campus. On September 10, a representative meeting was held at the Dhaka University Cafeteria, where almost all the colleges of the city were represented. The meeting announced a fresh action programme of hartal or total strike on September 17.

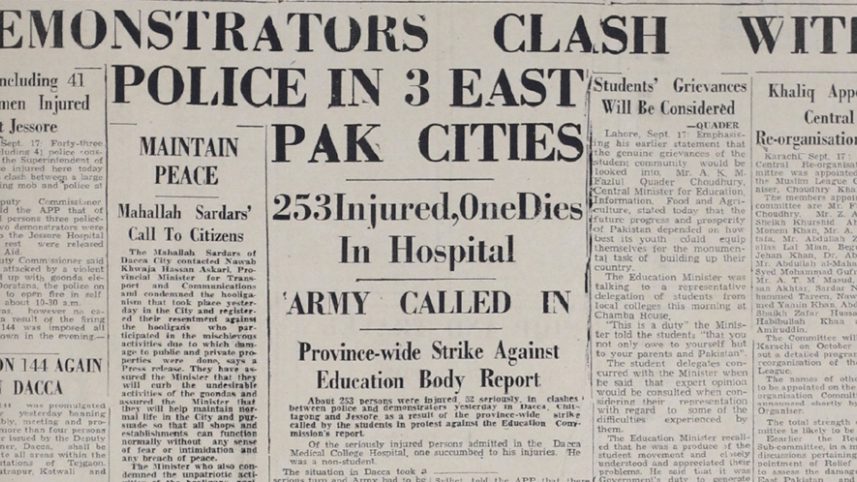

Street-corner meetings, processions, and talks with different organisations and associations of government employees, the rickshaw workers' union, labour unions, and various trade bodies were held to make the programme of September 17 a success. On the day, students began picketing from early morning. Agitating students set some vehicles ablaze as contingents of police chased demonstrators from Sadarghat to Nawabpur railway crossing. By 9 a.m., the Dhaka University campus was packed with students coming from different institutions across the city. It was virtually an unmanageable situation.

At that time, news spread like wildfire that police had fired at Nawabpur and a number of demonstrators had been killed. Hearing the news, a huge procession was brought out with Sirajul Alam Khan, Mohiuddin Ahmed, Rashed Khan Menon, Haider Akbar Khan Rono, Ayub Reza Chowdhury and Reza Ali at the forefront. Immediately after Kazi Zafar Ahmed made a short speech, the procession entered Abdul Gani Road near the High Court, where police fired on the back of the procession.

Babul, a student of Nobo Kumar High School, was killed instantaneously. Bus conductor Golam Mostafa, domestic worker Waziullah, and many others were seriously injured. Waziullah later died in hospital. The firing at Abdul Gani Road infuriated the processionists, which not only included students but also workers and employees of different mills and factories, rickshaw-pullers, and boatmen from the Buriganga river.

Two chief characteristics of the 1962 education movement deserve special mention. First, the movement was initiated by students alone, without any outside influence. Second, the central student leaders could not foresee that such a huge movement was possible based solely on education and academic problems faced by students.

Opposition leader Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy came to Dhaka from Karachi during the final stage of the movement. He met East Pakistan Governor Golam Faruq and persuaded him to defer implementation of the Sharif Commission Report. This resulted in the eventual end of the movement, which was an eye-opener to the vested interests in Pakistan's ruling coterie.

After 1952, students once again thwarted a veiled conspiracy against their mother tongue. For this reason, 17 September is observed every year, with the events of that day remembered and honoured.

Prof. Quazi Faruque Ahmed was the president of Bangladesh College Teachers' Association (BCTA),

The article was first published in The Daily Star on September 20, 2008. We have made some changes to improve readability.