The last of the Hoolocks

Bamboo groves, poised magnificently like arched gateways, welcome visitors to the misty woodland of Lawachhara National Park, the final frontier of the old forests.

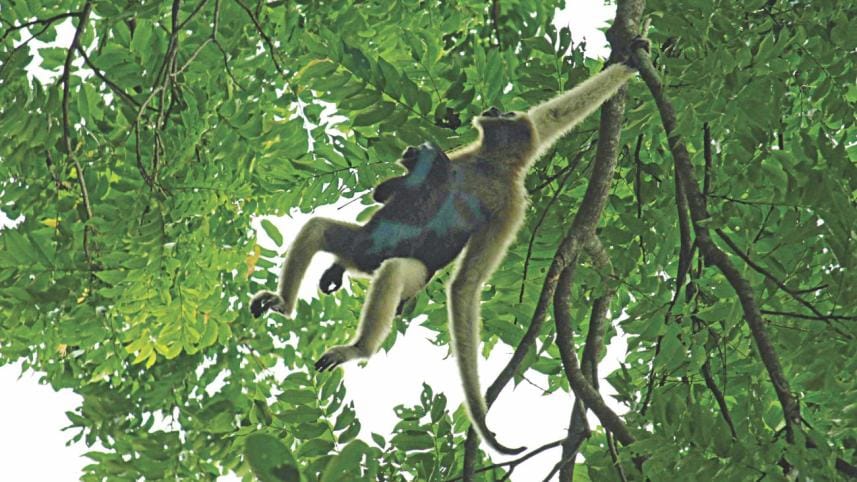

The towering trees that race towards the sun, with dense foliage enveloping every inch of earth on their path underneath, is where the last families of Hoolock gibbons find their only refuge.

Locally called Ulluk, each sex is coloured differently -- the males black with striking white brows and females grey-brown with a darker chest and neck -- and have rings around their eyes and mouths giving them a masked look; characteristics that make them a popular attraction for park visitors.

They are found in eastern Bangladesh and north eastern India, said Tabibur Rahman, former assistant conservator of wildlife management and nature conservation department in Moulvibazar, adding that a Hoolock has a lifespan of around 17 years and looks after its offspring for up to five years.

However, these primates are now considered critically endangered in Bangladesh.

According to a 2014-15 survey by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), only 250 Hoolock gibbons, also called western Hoolocks, are now found in Bangladesh.

This dwindling number is attributed to an acute lack of food, along with their shrinking habitat.

"Even just 10 years ago, the gibbons were found in large numbers and their calls could be heard frequently throughout the forest," Saju Marchiang, a forest guide, told this correspondent.

He added that due to deforestation, the Hoolocks' sources of food -- various fruits, leaves and flowers -- have depleted, pushing them to the brink of extinction.

Md Nurul Mohmain Milton, general secretary of Environmental Journalists' Forum, said illegal logging and other human activities have reduced the number of large trees, which the gibbons use for travelling and food, adding that there was a risk that gibbon populations would soon become isolated and restricted to only a few areas with tall trees.

A rainforest must be kept in its natural state and not be used for "gardening", he said, also claiming that the existing forest management's approach was still colonial.

Turning a blind eye to the hoolock's predicament and not taking action soon would result in the extinction of Lawachhara's most famous habitant and ultimately add another blow to its formerly illustrious list of megafauna.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments