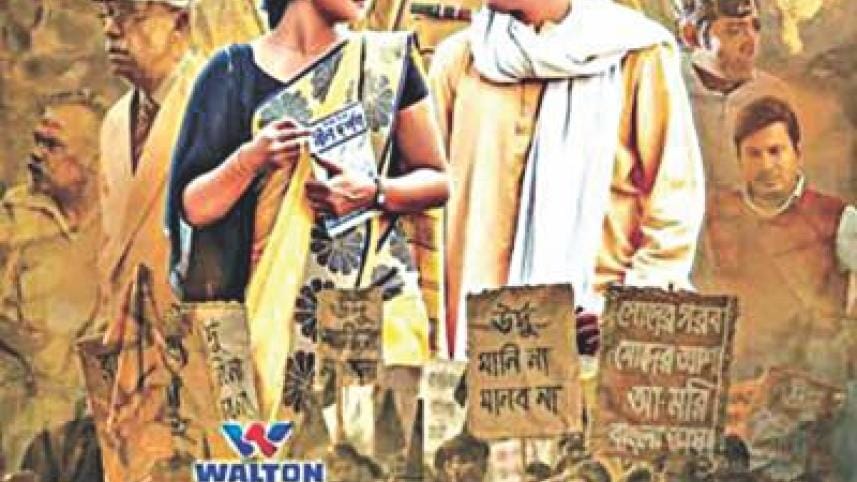

Capturing political history in film

We at the Seba Bangla Library in Atlanta recently screened Tauquir Ahmed's Fagun Haway (In Spring Breeze). The film, based on the 1952 language movement, is a mixed bag—while it truly soars in concept and approach, its execution is flawed.

The approach is smart. Instead of directly taking on the explosive politics of the 1952 movement in Dhaka, its take is more tangential.

Fagun Haway is set in a sleepy countryside town, far from the hurly-burly of Dhaka. The arrival of an Urdu-speaking police officer creates a big ripple in this quiet small town. The newly minted officer-in-charge, it turns out, is a rude boor bursting with cultural arrogance. Urdu, he declares, will be the language everybody speaks. People don't know it? Well, by God they better learn it fast.

This does not sit well with the townsfolk. The students of the town's college, the vanguard of the nation's conscience, are incensed. Matters come to a head as news filters in of the entire region rising up in arms.

The socio-political context of that era is murky. The memory of the 1947 partition is still fresh, and political honchos of the Muslim League, the key architect of partition, walk with a thug's menacing swagger, harbouring an ugly prejudice towards Hindus that they do not bother to hide.

It's a bracingly honest portrayal of that time.

What impressed me deeply was the director's guts and integrity to fly against the face of over half a century of Bengali cinema convention. It's really odd when you think about it, but go back all the way to the 1950s, and you will be hard-pressed to find a single Hindu character in a Bangladeshi/East Pakistani Bengali film or a Muslim character in a West Bengal film, although both regions have substantial minorities.

This is not a trivial matter. Films and books shape our views of the world around us. In the US, before the 1960s, schoolchildren grew up reading textbooks unsullied by images of non-white people. Popular US history failed to recognise non-white contributions. The civil rights movement in the 1960s brought much-needed awareness: textbooks have become inclusive; school children today learn that the first American to die in the American revolution was Crispus Attucks, an African American.

In Fagun Haway, the pain and humiliation of the genial, elderly Hindu doctor is shown with deep sensitivity and affection. The sweetshop owner and the director of the student play, both Hindus, are an integral part of the diverse Bengali community—which has been the reality that our films and TV have ignored for over half a century.

Ahmed is not unique—recent films Debi and Swapnajaal exhibited similar humane inclusiveness, a heartening development during an age of vicious sectarian schisms which Bangladesh has not escaped unscathed.

A word about the music. The romantic song "Fagun Haway" by Pintu Ghosh and Sukanya Majumder simply took my breath away. It's wondrously melodious, exquisitely rendered (especially Majumder), and tastefully picturised. (Good riddance to the dancing-around-trees scenes of my youth!)

However, the film does not do justice to Tauquir Ahmed's lofty reputation as the filmmaker of Haldaa (2017) and Oggatonama (2016).

First, Bangladeshi filmmakers simply should not attempt period films. We just lack the wherewithal. The Brits excel—look at their television shows like George Gently, Endeavour (both set in the 1960s), or my favourite, Miss Marple (set between the two World Wars). The meticulous attention to detail that brings a period to life requires the support of an entire industry of props and costumes that's simply beyond our means. I admire the presence of the vintage Volkswagen car, but there were several scenes—the home of the elderly doctor comes to mind—which were not convincing.

The acting itself and the positioning of actors often had a theatrical feel about it. Instead of nuanced, complex characters, many characters fill preordained slots—the valorous young hero, the supportive heroine, her firm and kind guardian, the avaricious Muslim League thug, his partner in crime.

Overall, the film's aesthetic veers closer to daytime soaps, where 30-year flashbacks happen at the drop of a hat, and high drama is all that matters, because indulgent viewers aren't terribly fastidious.

This film is far more ambitious, and it's a pity its drawbacks keep it from reaching its full potential.

Some recent films that captivated me include Roma, Cold War, Everybody Knows or The Salesman (which shares with Fagun Haway the storytelling device of having a play inside a film. In The Salesman it was—you guessed it—Arthur Miller's The Salesman.)

What all these films share—and alas, Fagun Haway does not—is a sum that is greater than the parts. And what are the parts? Sets that are realistic, messy and look lived-in, characters that are nuanced and act naturally, and cinematography that never gives the impression of facing a proscenium.

The sum of it all is that critical thing, verisimilitude—an illusion of reality so compelling that within a few minutes, a viewer forgets he/she is watching a film and feels as if by some magic he/she has been transported into a world where it's all happening.

For all its good intentions, Fagun Haway fails to do that. The film ends with a statement in English that sums up the historical importance that is marred by egregious typographical errors ("curfew," not "carfew"!)

It is still an admirable effort, and we were delighted to screen it in Atlanta.

Finally, a word about our screening. We were overjoyed to discover a minuscule but growing group of people who are repeat attendees. It's still tough going, but so what? We remain committed to screening good Bengali films in the future.

Ashfaque Swapan is a contributing editor for Siliconeer, a monthly periodical for South Asians in the United States.

Comments