The Islamic strain in Kazi Nazrul Islam

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

These words of a nineteenth-century American poet can very well be used to characterize Kazi Nazrul Islam. Nazrul also expressed his own contradictions brilliantly in "Bidrohi": "Momo ek hate banka bansher banshori, aar hate rono turjo." Translated into English by Kaiser Haq, they read: "In one hand I hold the tender bamboo flute/The trumpet of war in the other."

Nazrul's iconic poem uses both Islamic lore as well as Hindu myths to rebel against all that dehumanises and discriminates against human beings. Yet, this same poet used the memory of a glorious Islamic past to write poems denouncing the British Raj or calling for a revival of that glory. At the same time, he also wrote the most devout hamds and naats in praise of Allah and His Prophet.

That a child born in impoverished conditions in Churulia would grow up to write poetry, songs, fiction, political editorials, speeches and become the national poet of Bangladesh should have been impossible. But all these things did happen. As a child, growing up near a mosque, going to school in a maktab, often doing odd jobs in the mosque, his life should have been like that of countless villagers who die unknown and unsung. Or, introduced to the life of itinerant leto groups where he learned about Hindu myths and legends, he could have turned into a vagabond. But something happened to transform his life.

The most important change that took place in the life of a young man who was forced to earn a living from a tender age, whose schooling was only sporadic, was his enlisting in the 49th Bengali Regiment. Posted to Karachi, he was exposed to what he would never have known in Churulia or in the small towns to which his restless nature took him. In Karachi, for the first time, he not only got a regular salary which enabled him to subscribe to magazines from Kolkata, but also, despite the parades and marches, enough spare time to write. He had learned Arabic as a young boy, now he learned Persian. He read about communism and the Russian Revolution. He heard about the events taking place in the Middle East and the rise of Kemal Pasha. These events inspired Nazrul to write both poetry and fiction.

The poems "Kemal Pasha," "Ronobheri," "Bajichhe Damama" and "Shat-el Arab" reflect a Pan-Islamic influence. In "Shat-el-Arab," for example, he draws upon the history of the glorious Muslim past. In Syed Sajjad Husain's translation, the poem glorifies the place which witnessed so many battles:

Forever glorious, forever holy,

Your sacred beaches, Shat-el-Arab,

Are bathed in gore, the blood of fighters

Of many races, and diverse colours.

But at the time that Nazrul was writing, Arabia was as subjugated as India was. There is thus an elegiac note in the poem. Not satisfied with bemoaning a lost past, in "Bajichhe Damama" the poet gives a call to battle to restore the lost glory of Islam. In translation the lines read,

The war-drum is beating, tie your turbans and raise your heads high, O Muslims.

The flag flies from the broken fort. Prepare to build anew,

With the kalma on your lips, the sword in your hands

And the courage of Islam in your breast.

It was this same poet who wrote the iconoclastic "Bidrohi," celebrating the rebel as a superman whose head did not bow before any deity. He wrote "Anandamoyeer Agamoney," invoking Durga to destroy the British Raj as she had destroyed Mahishashur. He also wrote kirtan and shyama sangeet, devotional Hindu songs. At one time, Nazrul was writing so many devotional Hindu songs, that the wife of his friend, Dr Hamid, was very upset. Undaunted, Nazrul – who was well-known for the spontaneity with which he composed his pieces – wrote the hamd, "Ei Sundar Phal Sundar Phul Mitha Nadir Pani," punning upon the name of his friend's village: Sundarpur.

Along with other hamds in praise of Allah, Nazrul also wrote several naats, praises of the Prophet, regularly sung at milads today in Bangladesh. Apart from "Tora Dekhe Ja Amina Mayer Kole," where he images the Prophet as a baby, "The radiant full moon cradled . . . in the arms of dawn," he also wrote, "Saharate Phutlo Re," "Islamer Oi Sauda Loye," "Amar Priyo Hazrat." He wrote about Fateha Doazdaham, about Moharram, about the two Eids – the song "O Mon Ramzaner Oi Rojar Sheshe Elo Khushir Eid" is regularly played as soon as the Eid ul Fitr moon is sighted.

In other poems and songs, he wrote about the different obligations of a Muslim. In "Namaz Poro, Roza Rakho," he refers to prayers, fasting, the kalma, hajj, zakat, the Quran. In another song, "Hey Namazi Amar Ghore Namaz Poro Aaj," he admits that he does not always pray, but invites his friend to pray in his house and turn his house into a mosque. In "Masjideri Pashe Amar Kabar Diyo Bhai," he asks to be buried beside a mosque so that from his grave he may hear the muezzin's call to prayer, hear the footsteps of the faithful as they pass by, hear the sounds of the Quran being recited. The Government of Bangladesh did keep this request, burying him on the premises of the Dhaka University Mosque.

Before 1971, there was an attempt to make Nazrul an Islamic poet. "Hindu" words were changed to "Islamic" ones; words, phrases and stanzas were omitted. But Nazrul was not an Islamic poet. Married to Ashalata Sengupta, whom he renamed Pramila, he named his sons a combination of Hindu and Muslim names. And in his poems on socialism, he talks about a world where all religions coexist peacefully. In "Samyabadi," translated by Sajed Kamal as "I Sing of Equality," Nazrul embraces four major religions. But he also points out that it is not important to be a devout Hindu, Christian, Buddhist or Muslim. The greatest religion of all is the religion of humanity.

What I've heard, my friend, is not a lie:

There's no temple or Ka'aba

greater than this heart!

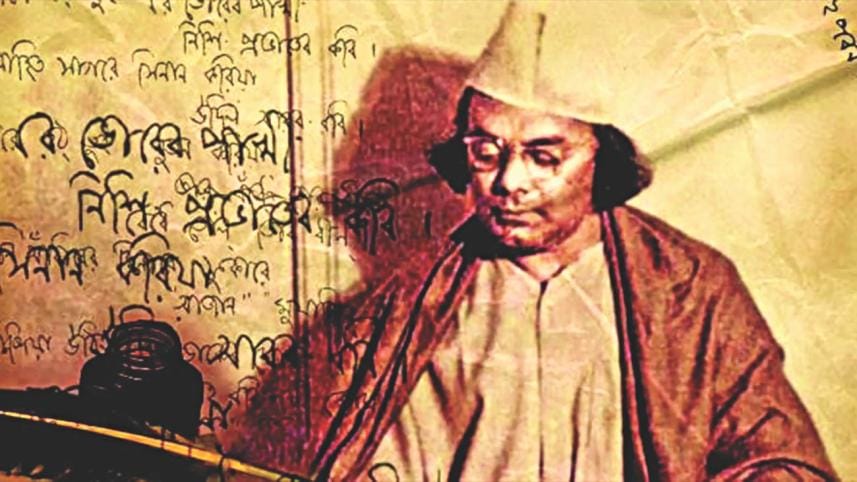

Photo: Collected

The writer is Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh, and a writer and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments