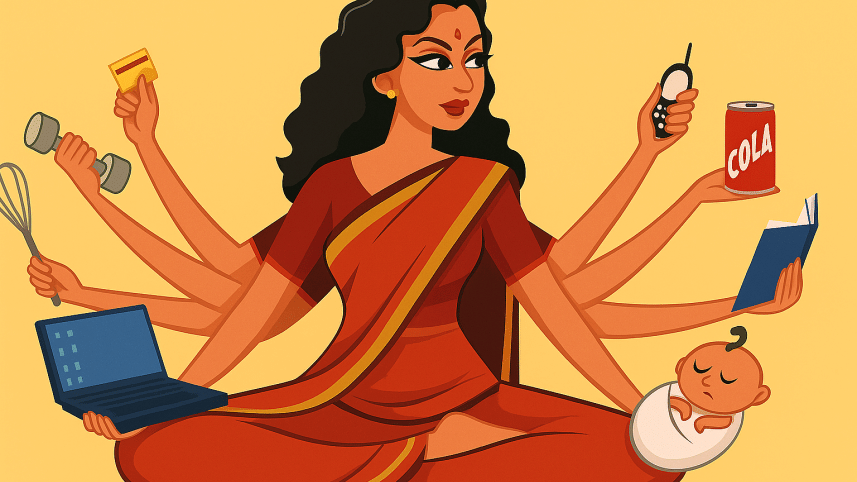

One woman, many roles — that’s every Bangladeshi woman

From managing offices to managing kitchens, Bangladeshi women navigate exhaustion, guilt, and invisibility. As women balance paid work with unpaid household labour, the cost is often their own mental health.

At barely 6 AM, Alifa Islam Monty was already on her second chore of the day. The full-time moderator for a popular skincare page had mapped out her day the night before. She warmed her infant son's breakfast while he slept, packed her daughter's schoolbag, checked her day's messages, and logged in to work.

"I schedule everything in advance so it doesn't all fall apart," Alifa Islam Monty said. "After getting my daughter ready for school, I sit at my computer for four or five hours of uninterrupted work. In between, I squeeze in 20 to 30 minutes to feed my son. When she comes home at lunch, I pick her up, cook, clean, serve everyone, then start working again."

Her tightly managed routine comes at a cost. By dusk, Monty is back in the kitchen preparing tea and dinner, then returns to her workstation. "Everything gets done, but there's no time for me, not even a proper shower or meal," she laughed.

Monty's story is familiar to millions of Bangladeshi women who perform what sociologists call a "double shift" — paid employment outside the home alongside the unpaid labour of housework and caregiving.

The strain of doing two full-time jobs, especially without recognition, can take a severe toll on mental health.

According to a recent study published in PMC PubMed Central on rural women in Mymensingh district, mental disorders are widespread. Studies show between 6.5 and 31 per cent of Bangladeshi adults live with mental disorders. In some villages, one in five women battles major depression, often in silence. Approximately 20 per cent of rural Bangladeshi women suffer from major depressive disorder.

Faysal Ahmed Rafi, a clinical psychologist and founder of Mindwizz, has been treating women experiencing what he calls 'slowly boiling exhaustion.'

"Women doing a double shift, both at home and outside, are not getting rest," he said. Long hours in unsafe workplaces, sexual harassment, and the guilt of not spending enough time with family combine to trigger chronic depression, anxiety, and phobias.

"We're seeing something tragic: after 40, many women develop psychosomatic illnesses, headaches, diabetes, chest pain, high blood pressure, because long-term stress literally eats them from within."

Mood swings and irritability, often dismissed as character flaws, are symptoms of constant crisis management.

He added, "They have almost no chance to calm down. Their tolerance drops, yet society brands them short-tempered instead of recognising the lack of self-care and mental health resources. Most women don't know where to seek help; they've never been educated on mental health. This neglect leads to conditions such as bipolar and borderline personality disorders appearing increasingly early in life. It's heartening that some women, thanks to growing awareness, are seeking help. But the majority tolerate the burden in silence and risk existential isolation."

He believes change must start at home: "If families and society acknowledge women's mental health needs and men share chores while children carry small responsibilities, the burden eases significantly."

For many working women, the burden is not just the hours but the sense that their labour is undervalued.

Tahsin Tanjin, 29, runs a small makeup business while caring for her nine-month-old. She laughed when asked about balance, though it sounded more like surrender. "At this age, he needs me 24/7… At the end of the day, it's my baby's needs that I sacrifice most.

She doesn't believe her unpaid labour is valued.

"It's a big no, never. It's impossible to be equally valued. Your in-laws and your husband take it for granted. They forget so easily what you've done," she said, her frustration palpable.

Sumaya Tasmim Kheya, 25, an MTO in Mercantile Bank, has tried to control the imbalance by controlling her hours.

"It's about prioritising," she said. "I refuse to spend so much time at the office that I can't see my family. I leave as early as possible, even if it slows my career. But if I can't give my family time, what's the point of working?"

She describes the trade-off as a choice between professional advancement and sanity.

"I don't think this should be a woman-specific problem," she said. "Why aren't men going home? Are they not helping their wives fix dinner? Men just leave the household duties to their wives. It's pathetic."

Sumaya's dual role is not a burden because of her supportive partner and in-laws. "If you have the right partner, it's never going to be a burden," she explained. "I earn money so I can manage my home better, that's my philosophy. Earning makes me feel like I'm contributing to our future, so that's empowering."

Her husband's family even prepares her breakfast and snacks so she can focus on work. But corporate culture still punishes her for choosing her family.

"In banking, bosses expect you to stay until 8:30 or 9 PM just to seem busy," she said. "I leave at 6 or 6:30 PM, and it will affect my career. They think I have no drive. But I'll always choose dinner with my family over a bonus."

In contrast, Tanin Sultana Sabiha, a housewife, aged 27, said watching other women juggle both roles make her feel "low…worthless." "I don't feel important anymore," she admitted. "My husband never belittles me for not having a job, but I definitely suffer for being unemployed. I could have walked out of situations where I was disrespected if I had a job."

Tanin's story highlights a cruel irony: domestic labour, though essential, is so devalued that women who "only" do housework feel expendable.

Men's perspectives underscore the tension between ideology and practice.

Samiul Bhuiya, a screenplay writer whose wife works full-time, compares domestic labour to kayaking.

"It's a joint role," he said. "Both need to paddle simultaneously to move forward. If one partner tries to handle everything, the relationship becomes unstable."

Shahriaj Mottakin, who works in banking, agreed that household responsibilities must be shared, though not necessarily split evenly. "It can never be 50:50 all the time," he noted. "Sometimes, it's 70:30, sometimes 40:60. But don't consider maintaining the household only a woman's job."

Finally, partners and families must step up. Faysal Ahmed Rafi insists that shared responsibility is the simplest mental health intervention. "Housework should not be taken for granted as 'women's work,'" he said. "When men share chores and children take on age-appropriate tasks, the woman's burden eases dramatically, benefiting everyone."

Back in her kitchen, Alifa Islam Monty closes her laptop and wipes her hands on her apron. She has just taken a call about a product launch while stirring daal, and the baby is starting to fuss.

"You keep going," she says when asked how she copes. "There isn't any other choice."

Her words carry resilience, but they also reveal the starkness of the bargain women have been forced to accept. Unless Bangladesh shares the load between partners, families, employers and policymakers, the silent labour keeping households and economies running will continue to exact a heavy, invisible toll.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments