Cyber security laws in Bangladesh: The ties that bind our past and present

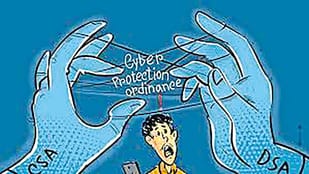

The cyber legal landscape of Bangladesh has witnessed a phase of transition in recent years, initially marked by the repealing of the controversial Digital Security Act (DSA), 2018 with the Cyber Security Act (CSA), 2023 and now replacing the Cyber Security Act with the Cyber Protection Ordinance (CPO), 2025. Even though every modification was presented by the government(s) as the betterment in the preservation of civil liberties alongside the protection of digital accessibility, legal experts and human rights activists have largely been concerned about there being mere re-labeling instead of substantive reforms.

The CSA, passed in September 2023, was brought in amid increasing domestic protests and continuing international criticism of the DSA's repressive provisions. While promoted as a liberal response to calls for protecting digital rights, the CSA retained the problematic areas from the previous law. Notably, section 42(1)(d) of the CSA retained the DSA's notorious provision regarding arrest without warrant, in the case of "reasonable suspicion" which continued to pose threats to whistle-blowers, journalists, and dissidents. Section 29 also retained criminal defamation, a violation of international human rights standards that favor civil remedies over penal sanctions for defamation.

Although the Act made certain offenses bailable and capped maximum penalties, it did not address the fundamental flaws in the predecessor. The phrasing remained vague, judicial oversight continued to be lax, and enforcement continued to be under the control of potentially biased actors. Amnesty International's report in August 2024 labeled the CSA as a missed opportunity, noting that it failed to live up to the standards of Bangladesh's international human rights commitments.

Enacted on May 21, 2025, the CPO replaced the CSA and formed part of the interim government's expressed commitment to re-establish democratic credibility and freedom of expression following the controversially contested national elections earlier in 2024. On paper at least, the CPO introduces several promising reforms. First, the ordinance repeals nine contentious provisions of the CSA, including provisions restricting speech that is critical of the Liberation War, national leaders, and constitutional institutions. It also introduces judicial oversight in case of content removals ordered by the government. Courts are required to review these actions afterwards and restore the content if the removal is found to be unjustified.

Significantly, the CPO is the first South Asian legal instrument to refer to cybercrimes using artificial intelligence (AI), acknowledging the emerging and evolving threats of deepfakes, AI-generated dis- and misinformation, and autonomous hacking networks. It also criminalises online sexual harassment of women and children with stricter sentencing guidelines and an apparent attempt to make definitions clearer, although the language remains vague and overly broad, still leaving scope for misinterpretation and potential abuse.

Furthermore, the CPO also brought forth an ideological shift by proclaiming internet access as a civil right and embracing the worldwide digital rights movement that sees connectivity as indispensable for education, work, and civic life in general.

Despite these reforms, there are several structural problems that remain. Under section 35(1)(d) the CPO still has a version of section 42, empowering warrantless arrests in situations concerning threats to national security using cyberterrorism, yet subject to a new proviso of post-arrest judicial review. However, critics argue that the judicial review mechanism offers limited protection in practice, as the broad and undefined scope of cyber-attack may still facilitate arbitrary arrests. On top of that, defamation remains a criminal offense under Section 28 of the ordinance, where it still complicates its definition.

Finally, some argue that the promulgation of the ordinance by an interim, unelected government, not subject to parliamentary debate, undermines its democratic legitimacy. The process was not transparent and subject to public consultation as such, two important hallmarks of responsible lawmaking in a constitutional democracy.

The transformation from the DSA to the CSA and then again to the CPO reflects a process of reactive regulation rather than true legal reform. Real reform indeed demands more than a change in acronyms or redrafting of provisions. Structural change is necessary: clear definition of cybercrimes, unqualified judicial discretion for content control, robust safeguards for online journalism and whistleblowing, and regulation or criminalisation of hate speech under well-structured guidelines.

In the long run, the government must conduct inclusive law-making processes with technologists, journalists, legal scholars, civil society groups, and the wider public. Then only can Bangladesh expect to enact a cyber law protecting its virtual boundary without compromising the democratic values of openness, accountability, and individual liberty. Although the CPO 2025 is an advancement in some ways at least, it is not yet a transformative legal instrument that the people of Bangladesh including the human rights defenders have longed for.

The writer studies law at the University of Dhaka and is official contributor at the Law Desk.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments