Business and Human Rights: The Pathway for Bangladesh

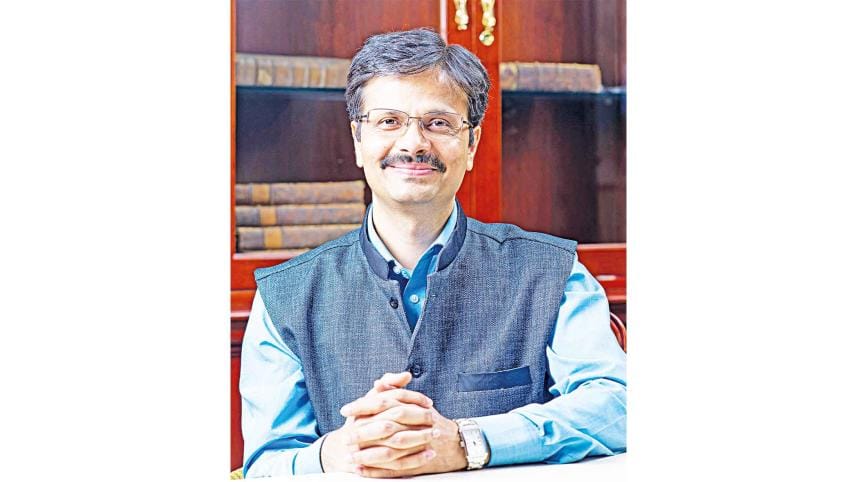

Surya Deva is a Professor at the Macquarie Law School and a founding Editor-in-Chief of Business and Human Rights Journal. He served as a member of the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights (2016-22) and has advised the UN agencies, governments, national human rights institutions, multinational corporations, trade unions and civil society organisations on issues related to business and human rights. Mohammad Golam Sarwar, Consultant, Law Desk, talks to him on the following issues.

Law Desk (LD): Bangladesh will soon be graduating from its LDC status. How will its compliance with human rights and international labour law standards impact its trade relationships with EU countries and other major investing nations?

Surya Deva (SD): International standards concerning human rights, labour rights and the environment are increasingly becoming an integral part of trade and investment regimes. After the unanimous endorsement of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) by the Human Rights Council in June 2011, neither states nor companies could afford to ignore the interface of human rights and business.

In this context, Bangladesh should see compliance with human and labour rights as a pre-condition for successful and sustainable trade relation with other states, specially the European Union. Instead of perceiving human rights as a compliance issue or a cost-increasing measure, Bangladesh should consider effective implementation of the UNGPs as a competitive advantage issue in the long run. Moreover, if businesses respect both people and the planet, this would create a more sustainable, inclusive and equal society in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In my view, the government of Bangladesh should take a holistic and long-term approach to economic development. It should introduce a range of incentives and disincentives for responsible business conduct. Moreover, the government should facilitate collaboration among companies, industry associations, trade unions and civil society organisations to achieve various national goals and overcome global challenges such as climate change.

LD: How has the pandemic impacted the performance of businesses' human rights and labour law compliance around the world?

SD: The Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the business and human agenda in paradoxical ways. On the one hand, many governments and companies started focusing on short-term recovery, economy revival and market survival, thus putting respect for human rights, labour rights and the environment on the back burner. On the other hand, the pandemic also exposed many inequalities and vulnerabilities in our current economic model – we all saw the plight of many children, women, migrants and workers part of the informal economy.

We should see the pandemic as a wake-up call. Building a more inclusive and sustainable society would require businesses pursing the path of "profit with principles". Respect for human rights and the environment should not be seen as an afterthought or merely a tick box exercise. Rather, achieving sustainability – which would require respecting all human rights and planetary boundaries – should be integrated as a cross-cutting goal for all government ministries and all business actors.

LD: Considering the emerging economy of Bangladesh, how do you see the challenges for localising business and human rights framework?

SD: Promoting responsible businesses conduct and holding companies accountable for abusing human rights or polluting the environment is proving to be a challenging task for all states. Bangladesh is no exception. However, given that the UNGPs are here to stay, the government should take a proactive approach in implementing the UNGPs and other business and human rights standards such as the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy. This would entail, among others, localising international standards to local conditions and circumstances in Bangladesh.

In my view, the government of Bangladesh should take several steps to operationalise the UNGPs in the local context. First of all, the government should make a public commitment to implement the UNGPs and start the process of developing a national action plan on business and human rights in meaningful consultation with all stakeholders. Such a plan should identify priorities for Bangladesh in short, medium and long terms.

Second, it should raise awareness and build capacity of companies (specially SMEs), workers, trade unions, consumers and civil society organisations in relation to international business and human rights standards. The National Human Rights Commission of Bangladesh and universities could play a key role in accomplishing this task.

Third, the government should strengthen its governance institutions at all levels and enhance transparency. Doing so will also assist in improving access to remedy for business-related human rights abuses. After all, the business and rights agenda is a sub-set of the wider discourse about respect for human rights, democracy and good governance.

Finally, government agencies and state-owned enterprises should lead from the front in respecting human rights, labour rights and the environment. By doing so, the government of Bangladesh would set a good example for private business actors.

LD: What are some of the ways in which Bangladesh can improve its performance concerning business and human rights? Is there any scope of regional and international cooperation?

SD: The government could learn from good practices elsewhere to move the business and human rights agenda in Bangladesh. For example, developing policy coherence among various government ministries will be essential. Equally important will be to break silos between agenda concerning business and human rights, the SDGs and climate change. Moreover, the government should link public procurement with responsible business conduct. It may also offer tax incentives and preferential loans for companies with a track record of respecting both people and the planet. At the same time, companies which do not get swayed by incentives should be held accountable to discourage free riding.

Many business and human rights challenges involve a cross-border or transnational element. Exploitation of migrant workers, environmental pollution, climate change and adverse impacts of new technologies are illustrative of this reality. Therefore, cooperation and collaboration with other states in South Asia and beyond will be essential. Collective action by states and business organisations should also help in accelerating the progress in implementing the UNGPs. We should also see the constant demand for an international treaty on business and human rights in this context.

LD: How do you evaluate the future of human rights and environmental compliance by businesses in a post-pandemic world?

SD: I feel that there is no turning back on increasing social and legal expectations from businesses to respect human rights and the environment. Because of various "push and pull" factors (including the mandatory human rights due diligence regulations emerging out of the European Union), most companies will feel encouraged or forced to take their human rights responsibilities seriously. In such a context, companies might be better off by adopting a proactive approach in moving towards socially responsible and sustainable business models. All stakeholders – from governments to investors, industry associations, trade unions, consumers, academia, lawyers and the media – have a role to play in ensuring that such a shift about the role and purpose of companies in society does take place.

LD: Many thanks for your time.

SD: You are welcome.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments