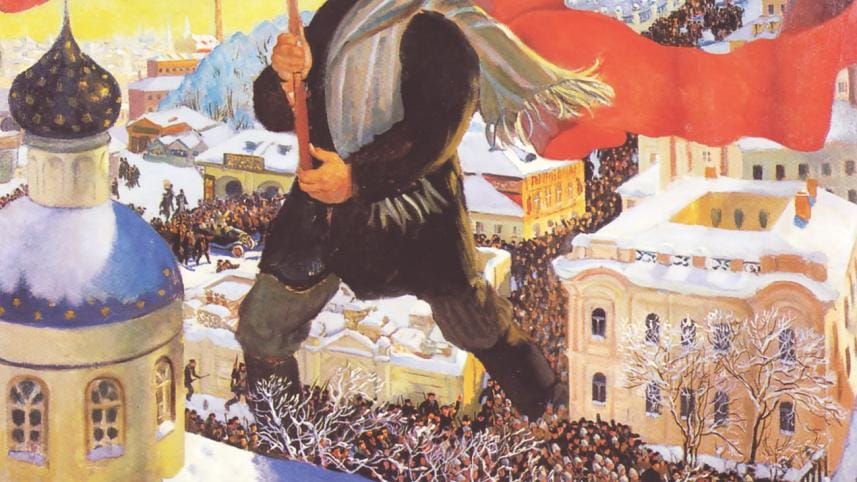

Was the Russian revolution a proletarian revolution?

On November 2, 1977, closing in on the sixtieth anniversary of the Russian revolution, the French historian Georges Haupt gave a provocative talk at the Fernand Braudel Center in Binghamton, New York. The title has been borrowed from that talk. Haupt said he too was given the title by others on the "Marxist and non-Marxist Left" who had been invoking the question for most of the sixty intervening years. Writing hundred years after the event that shook the world, I can hardly claim today that the terms of the debate have really changed much. I can only add that the dissolution of the USSR has rendered it rather more strident, indeed more topical. I also recall Georges Haupt qualifying his title a trifle farther: "In What Sense and to What Degree Was the Russian Revolution a Proletarian Revolution?" (Haupt 1979: 21).

I

Let me then begin at the beginning. It is interesting that an Italian internationalist and communist leader of the future, Antonio Gramsci, then hardly known beyond his native country, in making his first comments on events in Russia that overthrew the Tsarist autocracy asked the same question: "Why is the Russian revolution a proletarian revolution?" (Gramsci 1977: 28).

"The Russian revolution," Gramsci noted writing on April 29, 1917, "has destroyed authoritarianism and replaced it by universal suffrage, extending the vote to women too. It has replaced authoritarianism by liberty, the Constitution by the free voice of universal consciousness." "Why are the Russian revolutionaries not Jacobins," Gramsci then went on asking, "in other words, why have not they too replaced the dictatorship of one man by the dictatorship of an audacious minority ready to do anything that will ensure the program's victory?" (Gramsci 1977: 29).

The answer Gramsci supplied right away is of no less topical interest today. "It is because they are pursuing aims which are common to the vast majority of the population. They are certain that when the whole of the Russian proletariat is asked to make its choice, the reply cannot be in doubt. It is in everyone's mind, and will be transformed into an irrevocable decision just as soon as it can be expressed in an atmosphere of absolute spiritual freedom, without the voting being perverted by police interventions and by the threat of gallows or exile" (Gramsci 1977: 29).

There is indeed good food for thoughtful historians here. I for one almost shuddered at the first encounter with Antonio Gramsci making this audacious comment, within barely two months of the February revolution; for it was no less prophetic than Vladimir Lenin's famous April thesis. October was still a long way ahead. "Even culturally," Gramsci noted, "the industrial proletariat is ready for the transition; and the agricultural proletariat too, which is familiar with the traditional forms of communal communism, is prepared for the change to a new form of society." Prophecy was writ large no less in this comment of Gramsci's: "Socialist revolutionaries cannot be Jacobins: in Russia at the moment all they have to do is ensure that the bourgeois organs (the duma, [or the Russian parliament] the zemstvos [or the local government body]) do not indulge in Jacobinism, in order to secure an ambiguous response from universal suffrage and turn violence to their own ends" (Gramsci 1977: 29).

"Compared to the proletariat of the industrially advanced nations of Europe the Russian industrial working class was still a young breed, no doubt. But in 1917 this fact did not prevent a youthful working class from playing a leading role in the revolution. How was that possible?

Another important set of events, which the bourgeois newspapers hardly so much as noticed, caught Gramsci's eyes. "The Russian revolutionaries," noted Gramsci unmistakably in the wake of the first of the two revolutions of 1917, "have not only freed political prisoners, but common criminals as well. When the common criminals in one prison were told they were free, they replied that they felt they did not have the right to accept liberty because they had to expiate their crimes. In Odessa they gathered in the prison courtyard and of their own volition swore to become honest men and resolved to live by their own labors" (Gramsci 1977: 29).

"From the point of view of the socialist revolution," comments Gramsci, "this news has more importance even than that of the dismissal of the Tsar and the grand-dukes." Why?—one asks. "The Tsar," for Gramsci, "would have been deposed by bourgeois revolutionaries as well. But in bourgeois eyes, these condemned men would still have been the enemies of their order, the stealthy appropriators of their wealth and their tranquillity. In our eyes their liberation has this significance: what the revolution has created in Russia is a new way of life. It has not only replaced one power by another, it has replaced one way of life by another. It has created a new moral order, and in addition to the physical liberty of the individual, has established the liberty of the mind" (Gramsci 1977: 29-30).

What's so new about the "new moral order" then? Today, even such journalistic impressions of an Antonio Gramsci can hardly be dismissed as a utopian variant of bourgeois idealism. Let me add why. "The [Russian] revolutionaries," wrote our Italian revolutionary in all candour, "were not afraid to send back into circulation men whom bourgeois justice had stamped with the infamous brand 'previous offender,' men whom bourgeois justice had catalogued into various types of criminal delinquent. Only in an atmosphere of social turbulence could such an event occur, when the way of life and the prevailing mentality is changed. Liberty makes men free and widens their moral horizons; it turns the worst criminal under an authoritarian regime into a martyr for the cause of duty, a hero in the cause of honesty" (Gramsci 1977: 30).

What happened? "It says in a report," writes Gramsci, "that in one prison these criminals rejected liberty and elected themselves wardens. Why had they never done such a thing before? Because their prison was ringed by massive walls and their windows were barred? The men who went to free them must have looked very different from the tribunal judges and the prison warders, and these common criminals must have heard words very different from the ones they were used to, for their consciousness to be transformed in this way, for them to become suddenly so free as to be able to prefer segregation to liberty and to voluntarily impose an expiation on themselves. They must have felt the world had changed, that they too, the segregated, had the freedom to choose" (Gramsci 1977: 30).

This hundred-year-old Italian article, Notes on the Russian Revolution, concluded with this terse verdict: "This is the most majestic phenomenon that human history has ever produced." It's no meaner an observation than John Reed's more celebrated Ten Days That Shook the World. I quoted rather at length from this piece as I hardly encountered a reference to it in a hundred books and essays grinded in our staple-mills. Even commendable historians more often lose their way in a carnival of facts.

"As a result of the Russian revolution," Gramsci concludes, "the man who was a common criminal has turned into the sort of man whom Immanuel Kant, the theoretician of absolute ethical conduct, had called for—the sort of man who says: the immensity of the heavens above me, the imperative of my conscience within me." What import do these brief new items bear? What they "reveal to us," as Gramsci phrased it, "is a liberation of spirit, the establishment of a new moral awareness. It is the advent of a new order, one that coincides with everything our masters taught us." That the Western world, so-called, did not get it was quite clear. "And once again it is from the East," Gramsci could not help throwing in, "that light comes to illuminate the aged Western world, which is stupefied by the events and can oppose them with nothing but the banalities and stupidities of its hack-writes" (Gramsci 1977: 30).

II

What is so proletarian about the Kantian man, then? As Georges Haupt, who I will invoke to my profit, has pointed out that both the Paris commune of 1871 and the Russian revolution of 1917 have been called "revolutions in working-class clothes." "The problem," he writes, "is to see what is behind the clothes," what it means to be a revolution in working-class clothes. We have seen Gramsci using the word "revolution" in the title of his newspaper article. But that was about the February Revolution. Georges Haupt claims that the word "revolution" was never used during the October Revolution itself. The "October" days themselves, despite their world- shaking character, were perceived by contemporaries as more of a continuation than a radical upending of February.

A more interesting question awaits us here: how did October, when it eventually called itself a "revolution within a revolution," survive its many trials and tribulations? A proletarian revolution as a concept, according to Haupt, was not encountered before in the European revolutions of 1848. It was not for that matter centre-stage at the time, in any of the European heartlands, neither in France nor in Germany. Georges Haupt cites Marx and Engels. Karl Marx wrote, vintage 1848: "Even were the proletariat to overthrow the political domination of the bourgeoisie, its victory could only be transient, nothing but a passing moment in the service of the bourgeois as in Anno 1794." Frederick Engels also admitted: "Were the proletariat to come to power now, it would be able to realise only petit-bourgeois, but not directly proletarian measures. Our party can only take over a government when conditions permit us to realise this idea" (Haupt 1979: 25-26).

Compared to the proletariat of the industrially advanced nations of Europe the Russian industrial working class was still a young breed, no doubt. But in 1917 this fact did not prevent a youthful working class from playing a leading role in the revolution. How was that possible? It behoves us to take a short detour to the early years of the twentieth century if not far earlier.

What we call Russian revolution, from a long-term view, is a revolution in three episodes. Lenin called 1905 a "dress rehearsal" and, as Paul Dukes among others notes, he was the first to argue that October must follow on from February. So did Trotsky. The first event that made protest and disturbance spill into revolution occurred on January 9, 1905, better known as "Bloody Sunday". The beginning of 1905 saw a new wave of strikes rolling on the concentrations of the industrial working class in the capital and other megacities. A peaceful procession of strikers, women and children, proceeding towards the Winter Palace, was fired upon on January 9, 1905. The spell was broken. "Never again," as Dukes writes in October and the World: Perspectives on the Russian Revolution, "would the workers of the capital march with their wives and children in devout supplication to their Tsar under the influence of the oratory of a fervent priest." He also cites Lenin as noting: "The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence" (Dukes 1979: 78).

1905 was a "dress rehearsal" in another sense. The strikers in St Petersburg began to go back to work shortly after the firing, but there and in other cities workers were soon again taking to the streets, especially in Russia's colonial dependencies and peripheral territories such as Poland, and the Baltic and Caspian littorals. In the summer and autumn months the strike movement became more intense. The world owes the concept of the "Soviet" to a form of organisation Russian workers invented in 1905. This organisation popped up in October with the formation of St Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Deputies. Leon Trotsky, one of the 1905 leaders, comments: "It was an organisation which was authoritative and yet had no traditions; which could immediately involve a scattered mass of hundreds of thousands of people while having virtually no organisational machinery; which united the revolutionary currents within the proletariat; which was capable of initiative and spontaneous self-control—and most important of all, which could be brought out from underground within twenty-four hours" (Dukes 1979: 80).

Throughout the summer of 1905 industrial strikes continued, and troops too were called out, in one such case in Odessa it led to the mutiny of the famous Battleship Potemkin. In twelve years since 1905 things changed more than many historians could suspect. "Towards the end of 1916," as Paul Dukes grabs it, "the police department compared the situation in the new and old capitals with that to be found there ten or so years before, and concluded that 'now the mood of opposition has reached such extraordinary proportions as it did not approach by a long way among the broad masses in that troubled time'" (Dukes 1979: 85).

What triggered the events of February 1917 is, a whole century later, still a mystery to many. Did the World War bring forward the revolution or make it inevitable? As a telltale sign, January 9, 1917, the anniversary of Bloody Sunday, saw some 300,000 workers out in the streets of Petrograd (as wartime St Petersburg was being called) in demonstration. Paul Dukes summarises the situation: "From January to February the strike movement developed in the direction of revolution, particularly in the capital. Still using the experience of 1905, the workers of Petrograd had now moved twelve years on in their tactics and were also now in a position to take advantage of a much more promising military situation. While there were about one million men under arms, most of them away in the Far East, at the time of the first Revolution, there were fifteen times that number mobilised for the First World War, and nearly a third of a million in and around Petrograd, two and a half times as many as in peacetime, and a significant proportion of them workers and peasants" (Dukes 1979: 86).

Those who try to vilify the October Revolution usually oppose it to February. The February events, which triggered Tsarist autocracy's fall, actually began with Petrograd's working women's demonstration on Thursday, February 23 (March 8 according to the Western calendar), International Women's Day. Strikers from all over the city, in particular from the Putilov works in the southwest, and other workers, especially from the Vyborg in the northeast, joined. The number was close to 100,000 or more on the first day; on the second day the number almost doubled. The way to another Bloody Sunday was in the making by February 25. The point of no return was reached when fire was opened on a few hundred of demonstrators. But by February 26–27, revolutionary workers were joined in by mutinous troops who refused to fire on the unarmed civilians. The point of no return was reached at long last. With soldiers won over, the Russian revolution properly so-called began. The Tsar, Nicholas II, did not abdicate until March 2. October was yet far from a cut and dried piece of cake. All I can do here, given this space, is throw in a comment: October was no automatic repetition of February; it was rather a repetition with a difference.

Salimullah Khan is Professor at General Education Department, ULAB.

The October Revolution started with an armed insurrection in Petrograd on October 25, 1917 of the Julian Calendar, which is November 7 of the Gregorian Calendar now in global use.

Comments