Imagining a Dhaka for 2035

No one doubts the magnitude of complexity that shrouds Dhaka, this city of 16 million poised between being the worst liveable and an economic colossus. The more complex a city is, the greater the need for dare and innovation in envisioning its future. Overwhelmed by conventional practices and policies, most planning initiatives are discouraged from considering innovative possibilities.

The 2016-2035 Detailed Area Plan (DAP) takes on the challenges of this complex city with an impressive and detailed document that has also spurred furious discussions on its pros and cons. Those of us who study the destiny of cities feel that, despite being extensive, this draft document is yet to articulate or expand some key issues that drive a city. The principles of details are in those critical issues, which are discussed below.

Dhaka city has an outer reach and in-reach

The dynamic of Dhaka city cannot be constrained within the administrative or juridical boundary of Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (RAJUK). While understandably the DAP is mandated to operate within that boundary, the DAP area must be situated in a broader regional context with an understanding of various linkages with the larger setting. We consider this to be the "outer reach" of Dhaka city. Even within the juridical boundary, some areas are poorly addressed from the perspective of the prioritised metropolitan core – we call this the "in-reach" of the DAP area. A conceptual understanding of this double scope is needed for preparing any plan for Dhaka.

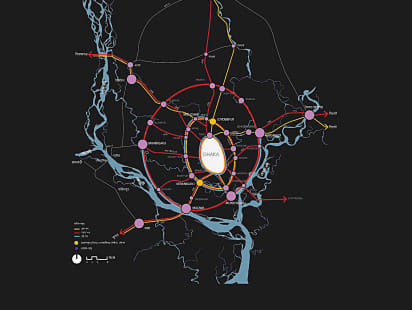

The Dhaka Structural Plan (2016-35), for instance, proposes a polycentric arrangement for a greater Dhaka. Such a proposition has not been taken up yet as it requires the intervention of the central government and its multiple agencies. The idea of a polycentric megacity aligns with what we have proposed in a regional plan for Dhaka – described as "Dhaka Nexus" – in which a metropolitan core and diverse settlements, in a two-hour travel radius linked by an efficient transport network, create a planned constellation or conurbation. This new conurbation of urban nodes may be effective in decentring the metropolitan core as well as re-clustering urban facilities and managing density. Urban nodes can be existing towns or settlements, or in some cases, new planned ones.

Most planning discussions on Dhaka circle around the metropolitan centre, constituted by the two prominent city corporations, the Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) and the Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC), but the planning scope of RAJUK Dhaka includes four city corporations, three municipalities, and their diverse territories. Beyond metropolitan Dhaka there is also a burgeoning landscape – a heterogeneity of small townships, villages, transforming villages, spontaneous settlements, industrial patches, agricultural land, flood plains, forest leftovers, and diverse wetlands. This is the "in-reach" of RAJUK Dhaka. Considering this incredibly diversified landscape, it is not enough to bring all of that under a single regulatory mechanism by a diktat ("nitimalas" and "bidhimalas"), or a land-use proclamation, and feel self-satisfied that things are taken care of.

The heterogeneous landscape described above poses a conceptual challenge to planning, which the DAP document does not take up in any pronounced way. We need to first conceive this vast conurbation in proper strategic terms. How do we plan for this diversity? Will their developmental trajectories be the same? Will it be a planned singularity in which all become one? What kind of oneness? Should it develop as a planned heterogeneity, in which the distinctiveness of each social and morphological cluster is maintained and advanced? In that case, how will each develop, and with what kind of interrelationships? Or, should we give up to a singleness that will happen anyway in the dynamics of the homogenising market mechanism?

A vast area, named in the DAP land-use category as agricultural land (29.48 percent in metropolitan Dhaka), poses another planning dilemma, especially peculiar to Dhaka: How agricultural areas be brought within the folds of the city? Is it enough to simply assign agricultural land-use? We have come up with creative plans on amalgamating those agrographic areas with the metropolitan milieu. Since the preservation of such areas concerns food and ecological security, there should be a different and distinctive detailed plan for such transformational landscapes beyond the suggestions in the DAP.

Water flow as basis of urban plans

If the agricultural terrain within the city jurisdiction describes what I call "agrography," land under a water regime can be called "terraqueous" (formed of land and water). Reviewing the RAJUK/DAP area, we see enormous areas under a water regime, whether as wetlands, flood-flow areas, rivers, retention areas or agricultural lands (flood zones and agricultural areas may be spatially coterminous in that they alternate with the seasons). I have previously argued that, for much of Dhaka, there is a need to think beyond "land-use" planning. With an innovative approach of "land-water-use" planning, we can reorient our water-use terminologies, in which flood, instead of a calamity, is considered as a terraqueous phenomenon. It may sound repetitive, but Dhaka needs, first of all, a "terraqueous plan."

For cities of water, the Chinese ecological planner Kongjian Yu has developed a "sponge city" concept in which the flow of water, its absorptive management and ecological and civic benefits define a new hydrological infrastructure for a city. He has carried out successful plans for several Chinese cities, the principles of which have been adopted as national policies by the Chinese government. We realise that all cities under the spell of monsoon Asia or the dynamics of delta rivers – both enjoyed by Dhaka – should have hydrological infrastructure as a priority. Planning decisions should begin from there.

Rivers, canals, wetlands, floodplains, storm-water, all create a "water flow" system and should be treated in a special way. Installations, constructions and developments need to be considered with new conceptual thinking. Arfar Razi, a senior geographer at Bengal Institute, has developed a watershed map for principal rivers in and around Dhaka in which he identifies four hydrological regimes that should be foundational for all urban plans. Any infrastructural intervention or large-scale construction should be directed by the watershed system.

A creditable inclusion in the DAP document is how new constructions may be carried out in flood-flow zones. Most unauthorised structures, the DAP document shows, are in areas with the biggest potential for ecological damage. I believe that illegality is not so much about the abuse of land-use regulations but a lack of constructional vision for the terraqueous zones.

We have to develop our own theory of the city, as well as our own techniques for critical ecological areas. For floodplains and terraqueous areas, as with agrographic lands, we need dedicated and specialised plans. As an example, we have imagined a belt of dense and special building development in the periphery of those areas that can frame and protect the precious terraqueous areas.

Riverbanks and canal-banks present another critical and vulnerable condition. One reason that we have been vandalising the riverbanks is that we do not know what to do there, and what is the best option as a common good. It also appears that liberating a khal or river from encroachment is not enough; we need exemplary language and guidelines. Architects at Bengal Institute are working to develop a language and typology for big city riverbanks, from the Buriganga in Dhaka to the Sitalakhya in Naryanganj and the Surma in Sylhet.

Following the DAP's "leverage points", we suggest robust attention should be given to riverbanks and canal-banks as catalysts for creating a new public realm for Dhaka and advancing an ecological and economic resource.

Transport infrastructure will change the city for better

Transport vitality is the single-most effective impetus for a better Dhaka – it is not only the carrier of peoples but leverage for urban development. We are inspired to see that transport infrastructure has been a major investment area of the government. Even though slightly belated, and often troubled with route lines, mass rapid transport (MRT) lines will catapult Dhaka city into the 21st century. In response to the upcoming transport infrastructure, the city needs a robust, comprehensive plan.

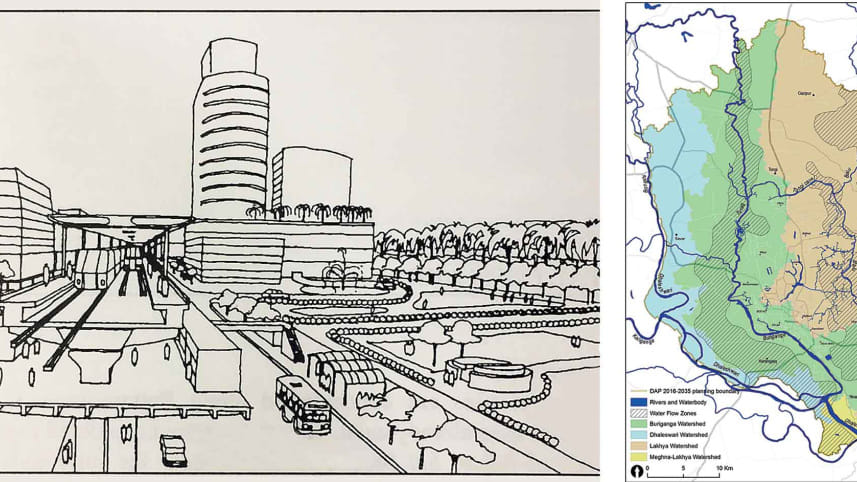

An MRT system, and the various projected ring road and rail lines, should not be seen as an independent driver in the city's development trajectories. As in Tokyo in the 1960s, and Singapore and Bangkok recently, stations in transport lines are planned as new urban hubs with civic and commercial consequences. The city literally grows around those hubs. We refer to "The Bangkok Plan" of the 1980s that instead of a master plan focused on developing the city around the station-based hubs.

There could be, in the DAP plan, greater suggestions regarding potential station hubs in the upcoming transport arteries. Since each station is a TOD-driven development cue, there should be detailed development guidelines for each station area in the context of specific neighbourhoods or wards.

The success of any mass transit system relies on good walkability, which there is a pathetic lack of in Dhaka. To produce a civic, healthier, and efficient Dhaka, and to align with the station hubs of the MRT lines, a more detailed walkability plan should have been in the DAP.

Housing is an urban form

The idea of "block housing" for creating the residential fabric of the city, recommended in the DAP, is praiseworthy as housing – or rather the lack of it – continues to be the misery of Dhaka. I have lamented since the 1990s that making plots and individual buildings do not make the best city, either in the proper use of land or creating communities.

There are critical questions that need to be addressed with "block housing": How will RAJUK generate such block housing in the current market climate under its own entrenched practice of encouraging ferocious plot-making? What are the different models for block housing? How will they be generated? One assumes the viability of block housing for new areas, but can it be engineered for existing plotted situations, or even densely built areas?

Block housing also raises the matter of "urban forms," in which areas of the city are visualised through density planning, environmental condition, and common spaces. As this will be a new practice, with most people unaware of its viability, it is important that the DAP demonstrate models of urban block through exercises and exhibitions.

While the modulation of housing form and density is easier for new, unbuilt areas, it is a greater challenge for densely built-up areas that are challenged in liveability factors. How can a decent environment be given to neighbourhoods like Jurain, Basabo and Shewrapara? To interventions already proposed in the DAP, we suggest consolidated plot-clustering and land pulling that can be incentivised by loans or tax cuts. For such innovative ideas, it is important to have a few visible models.

Public space needs legal recognition

A critical category in the humanistic and civic experience of a city, public space defines the character of great cities – Siena by Piazza del Campo, Venice by St Mark's Square, Isfahan by Maidan-i-Shah, Kolkata by the Maidan, and Manhattan by Central Park. Such spaces signify what the city leaders designate as the "commons" for all -- living rooms that house the city's life and energy. Public spaces can be as glorified as those listed above but can also be small, unpretentious spaces. The global pandemic has ushered a new urgency around public health and a deep necessity of public spaces in the city, whether as plazas, "chottors," parks, fields and gardens.

A discussion of public space remains marginal and fuzzy in our public discourse. Such a gap has been sadly officialised in all documents through a long history of disregard for public spaces in a space-embattled city as Dhaka.

The DAP identifies 13 types of land-uses, of which "open space" is one (1.04 percent in the metropolitan area). All public spaces are open spaces, but the reverse is not always true. While open spaces may include setbacks between buildings, as well as forests and regional parks, they will not necessarily be public spaces. If a plan for Dhaka aspires to be socially inclusive and humanistic, as the DAP claims, it should begin with generous attention to public spaces. Going forward, we urge for an exclusive "bidhimala" for public spaces, and incentives for generating public spaces at all scales, from the city to the neighbourhood and the corner of a street. We have argued that the footpath is a linear public space; it should receive extensive treatment in the final document.

While we appreciate RAJUK's presenting fresh ideas in its draft DAP, we suggest a more prolonged dialogue for finalising the blueprint for the future city. We also suggest that for all new ideas – neighbourhood hubs, land transfer, floodplain constructions, block housing, and ideas suggested here – architecture and planning schools in the country are invited to produce visualisations that common people can understand. Words, and certainly regulatory language, are not enough to convey the qualities of new urban ideas. We have to agree that concerted efforts are needed to create a Dhaka for 2035.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and urban designer. He is currently the Director-General of the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements. He is the author of "Designing Dhaka: A Manifesto for a Better City." This article was prepared with the support of Nusrat Sumaiya, Arfar Razi and team at Bengal Institute.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments