Pahela Baishakh: Look back at roots of the festival

Taxation systems must have gone through many reforms over the past 400 years. But perhaps nothing was so phenomenal than the one reform that took place in 1585.

In those Akbar days, the very introduction of Tarikh-e-Elahi -- a solar calendar in place of the lunar one -- brought much relief to the agrarian communities of the then Bengal as well as many other parts of the subcontinent because it made the calculation of date and months more scientific. Also, it was in consistent with the harvesting season, thereby facilitating the Moghuls in better revenue collections.

Though introduced in 1585, the Tarikh-e-Elahi, also referred to as Fasli San (crop year), dates back to Emperor Akbar's accession to the throne in 1556. The New Year subsequently came to be known as Bangabda or Bangla year in our part of the world.

Eventually it became customary to clear up all dues on the last day of Chaitra, the last month of solar Bengali calendar, and businessmen treating their customers with sweets. Arrangements of village fairs and other festivities became part of a rich cultural heritage.

Some 432 years later, the celebration of Pahela Baishakh comes to us today at such a critical juncture of time when a section of people are trying, in vain, to extract “new meaning” of what has been all through a non-communal national cultural journey.

Pleasantly, though, an overwhelming majority -- irrespective of their cast and creed and religious beliefs -- consider the Pahela Baishakh as a day of merriment, as a day of reinvigorating rich national culture and heritage, and there is nothing irreligious in it.

It's true that over the years the New Year celebrations have shed many rituals while inducting newer forms and events to rejoice but the core value of upholding own language, history, culture and heritage still remain the celebration's centrepiece.

Many old festivals connected with New Year's Day are no longer practised. On the other hand, new festivals have been introduced. Though agricultural in origins, the Pahela Baishakh festivities are now more marked in urban societies than in rural societies.

With a vividly colourful and pompous rally called Mangal Shobhajatra -- the centrepiece of the Pahela Baishakh observance -- being recently recognised by the United Nations as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, this year's celebration is set to reach a new height.

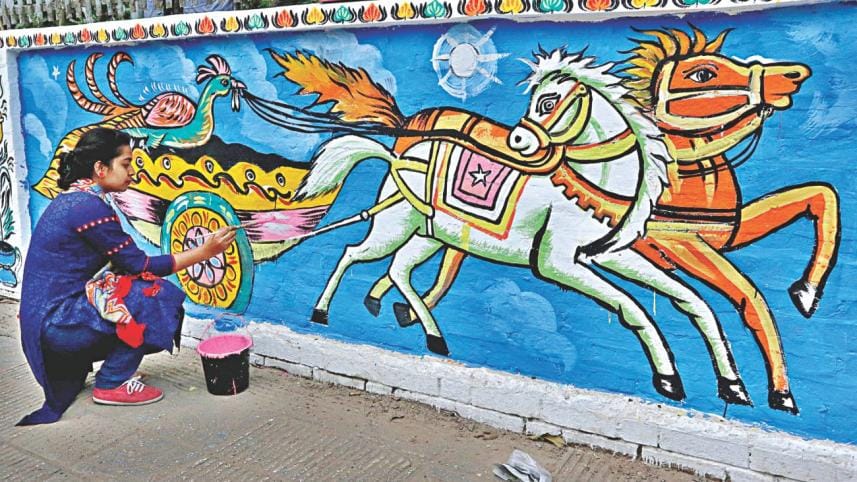

Stray incidents of attack on the Pahela Baishakh murals in Chittagong would in no way dampen the indomitable spirit of a nation.

In view of the Unesco, "The Mangal Shobhajatra festival symbolises the pride the people of Bangladesh have in their folk heritage, as well as their strength and courage to fight against sinister forces, and their vindication of truth and justice. It also represents solidarity and a shared value for democracy, uniting people irrespective of caste, creed, religion, gender or age. Knowledge and skills are transmitted by students and teachers within the community."

As the sound of drums beating resonates through the streets, onlookers feel a deep yearning to join Mangal Shobhajatra and that is the beauty of it.

People from all walks of life have been showing enthusiasm more and more for participating in the procession organised by the Faculty of Fine Arts of Dhaka University on Pahela Baishakh every year since 1989.

Traditional village fairs, folk festivals and Mangal Shobhajatra apart, rendition of music by the Chhayanaut artistes under the banyan tree in the open of Ramna remains a rich part of a long tradition. And opening of new ledger book (Hal Khata) by business people, having pantha-ilish (Hilsa and watery rice) delicacy have all become part of the celebration.

Islamic scholar Syed Ashraf Ali once wrote it was the New Year celebration that enabled Prince Selim (later Emperor Jahangir) to meet and fall in love with Meherunnisa (known as Nurjahan in history). It was again in one such new year festival that the Prince Khurram (later Emperor Shahjahan) first came across Mumtaz Mahal, whom he immortalised through the great “poetry in marble” -- Taj Mahal.

"Had there been no Nobobarsha festival, there perhaps would be no Nurjahan, and no Taj Mahal," said the late scholar.

Our very own great Bengali poet Tagore told us not to be afraid of northwester as and when it darkened the evening sky.

In his verse “Oi Bujhi Kalboishakhi” Rabindranath Tagore says (as translated by Dr Fakhrul Alam),

"There it comes -- Boisakh's seasonal thundershower

Enveloping the evening sky!

What or who do you fear? Open all doors everywhere

Listen to the sky rumble intensely and its loud insistent call.

Respond to its overture with song-lyrics and melodies

Let whatever shakable shake; let anything transient go!

Let everything fragile shatter; let only the permanent stay!"

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments