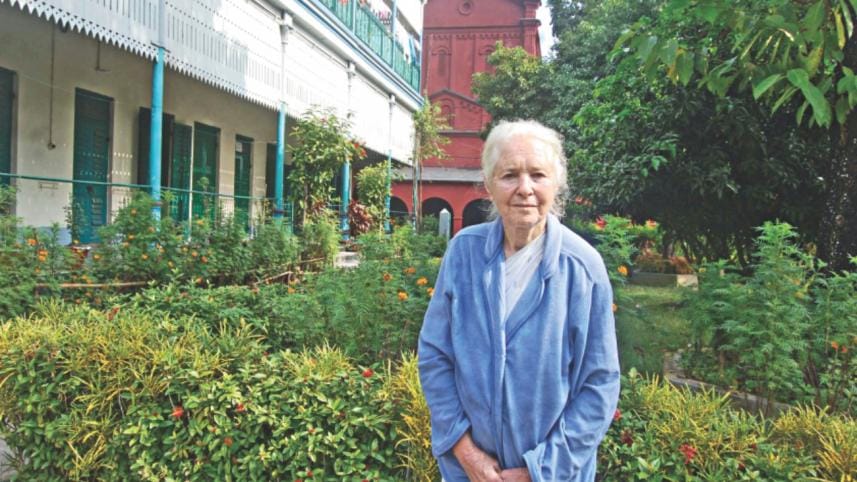

A Briton with a Bangladeshi Heart

In 1960, British citizen and graduate Lucy Helen Frances Holt left the land of her birth and travelled to then East Pakistan to pursue humanitarian work as a Catholic Sister. Little could she have realised that, through war and peace, it's where she would stay.

“I worked as an orderly at the Fatema Hospital in Jessore during the Liberation War,” she says. “Though I was not a doctor I treated many patients because the number of doctors was quite insufficient to attend to everybody's needs. Indeed the doctors weren't always there; some days they felt it was too risky to go to the hospital as usual.”

She provided care to all, she recalls, whether freedom fighter or civilian. At times she treated bullet wounds. “I was really fortunate to be able to contribute to the country's liberation,” Sister Lucy says.

She also wrote many letters to friends in England from the eve of the war in 1971, advocating support for Bangladeshi independence. Her letters were well-received. “I wrote of my admiration for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Bangabandhu,” she says.

“Actually I admired him so much that in 1972 I sent a handkerchief I'd embroidered as a gift to his wife.” Bangabandhu's youngest daughter Sheikh Rehana responded to the gift by letter, on behalf of her mother.

Interestingly, as though her connection to Bangladesh was pre-ordained, Sister Lucy was born on 16 December, the same date as the country's Victory Day. This year while Bangladesh celebrated the 46th Victory Day, Sister Lucy also celebrated her own 87th birthday.

This year too, for the first time, Sister Lucy's contribution to the Liberation War was recognised. She received an award courtesy of the Barisal Metropolitan Police. In her acceptance speech she confessed her belief that her contribution had been forgotten and that nobody remembered her, which made the award ceremony particularly joyous for her.

“I am really grateful to the police for remembering me and calling me here to speak,” she said. “In my life this is the greatest gift of all.”

Asked why she never left Bangladesh, Sister Lucy speaks of her limitless love for this country and its people. Indeed she was requested to leave at the beginning of the Liberation War but she insisted on staying by the side of the 'freedom loving people' of the delta.

Sister Lucy is still engaged in social work. She currently teaches English for free at the Barisal Oxford Mission Primary School. “I would like to continue if I am permitted,” she says. “I like teaching English to the students, not with a focus on exams but for their general education. I also want to teach mothers about the best childcare practices.”

Sister Lucy has one final wish: She wants to be a Bangladeshi citizen and to be buried in the delta's earth so that forevermore she and her beloved Bangladesh will be together.

At the moment the British citizen has to pay around Tk 35,000 annually to renew her visa, which she finds difficult to manage. It's a situation that may change soon.

“For Lucy's dual citizenship I've spoken with the immigration police in Dhaka,” says S M Ruhul Amin, the commissioner of Barisal Metropolitan Police. “I've asked them to take all necessary steps to arrange her dual citizenship.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments