Climate compensation schemes 'failing to reach poorest'

Remote communities are not receiving the compensation they are entitled to from schemes designed to conserve tropical forests, a study suggests.

People who depend on being able to harvest forest resources should receive payment under the schemes.

But researchers say there is a "reality gap" between safeguards designed to help affected communities and who actually receives the compensation.

The findings have been published online in Global Environment Change.

"About 11% of global emissions come from deforestation and degradation of tropical forests so the idea is that if you can slow this down then that can offset emissions and that is good for climate mitigation," explained Julia Jones from Bangor University, Wales.

Over the past decade, schemes called Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (Redd/Redd+) have been developed as part of the global effort to mitigate climate change.

These mechanisms are designed to improve forest management and reduce the net emission of greenhouse gases in tropical forest and sub-tropical forest nations.

"It finally got approval (at the UN climate summit) in Paris in December that Redd+ will go ahead as a global climate mitigation mechanism," Prof Jones told BBC News.

"What that means in reality is more protected areas and more funding. This sounds brilliant, after all it is a win-win situation and what is there not to like about it?"

However, it has been widely acknowledged that such schemes - if not implemented properly - can have a significant negative impact on people's livelihoods, such as indigenous communities, and exacerbate poverty.

"This has been taken on board by, for example, the World Bank," observed Prof Jones.

"They have made commitments that anything they fund [and] people are displaced as a result, they must be compensated for it.

"Principles that protected areas should not harm local communities have also been recognised by the [International Union for Conservation of Nature, for example"

But she added: "The problem is how do you go about doing that? The way that the World Bank guidelines work is that households affected by a scheme must be identified and then compensated for the negative impact of the establishment of a protected area on their livelihoods."

In order to test whether the commitment to "social safeguards" were working on the ground, the team of UK and Malagasy researchers looked in detail at an area within Madagascar where a new protected area was being established.

"We have shown that, yes, they have gone out there and identified households that they think are affected negatively by conservation and have delivered compensation."

However, she added, the compensation was not reaching those most affected by the project.

"We have mapped every single household that should have been covered by the compensation and have shown that… the process had some very serious biases in it," she said.

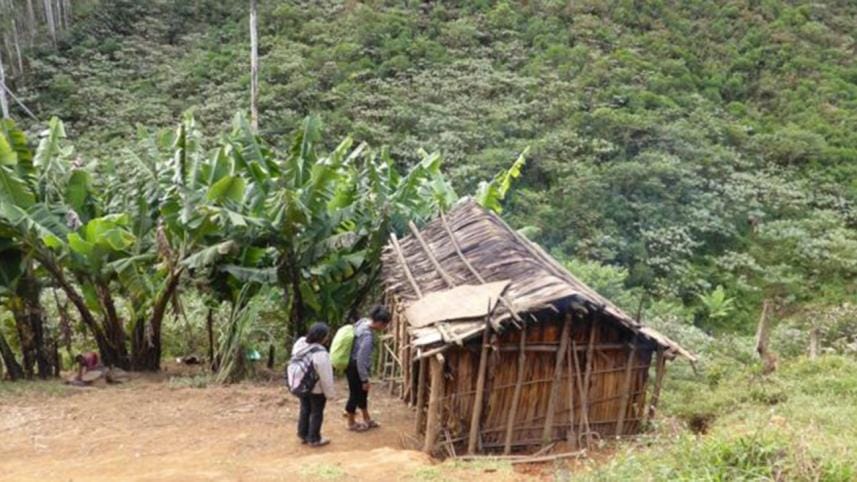

"Essentially, the people that were identified were easier to reach physically - such as closer to the road or closer to the administrative centre.

"They also tended to be more socially connected; members of local forestry management committees, and they were - on average - richer or, at least, less poor."

Prof Jones said it was not what would be expected from a scheme that was delivering the help where it was needed most.

"People that are closer to the administrative centre are further away from the forest so they are less dependent on forest resources for their livelihoods," she suggested.

[media type="image" id="131782" layout="small" caption="1"]

"What is interesting here is that the World Bank has very explicit guidelines that it has to be pro-poor and target vulnerable groups. We have shown that it is not working."

She said the study required researchers to spend a long time in the area in order to learn where all the households were located. In some cases, team members had to walk for eight or nine hours in order to reach some of the most remote communities.

'Reality gap'

"A criticism is that you can miss households like that if you come in for a short period of time but this is one of the problems; you cannot expect consultants paid through a World Bank project to be putting in that level of effort to find individual households," she added.

"We do not want to be criticising the individual implementers of that particular project but we want to highlight a 'reality gap' between these lovely policies that sound great on paper and the reality on the ground which is that it is incredibly difficult to implement these policies."

Prof Jones said the study's aim was not to pass judgement on the projects nor the way the compensation scheme was implemented.

There is value pointing out that there is this reality gap," she added.

"In countries like Madagascar, there is such poor mapping so when you are planning something like this and you do not have a map that shows villages that have primary schools etc then you are not going to be allocating sufficient resources.

"I would say that whenever there is any sort of effort to implement a conservation scheme then there needs to be an effort to map the human population. Relying on very old and out-of-date maps is not sufficient."

The team suggested that providing compensation to all households in an affected area would prove to be more financially efficient, as the cost of providing the resources needed to map and assess households "may not be feasible".

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments