Understanding the cinema of convenient truths and perfect propaganda

Cinema has always been a mirror, but particularly in the last decade, it has started holding that mirror at a rather flattering angle. The reflection now has a bit more nationalism, a bit less nuance, and sometimes, an entire political manifesto playing in the background. The trailer for "The Taj Story", which asks whether the Taj Mahal might once have been a temple, does not merely invite curiosity; it stages curiosity as corrective history. It is the newest actor in a growing ensemble of movies that treat doubt like doctrine and cinema like a courthouse. And while we once saw filmmakers wrestle with moral ambiguity; in present times, the only ambiguity lies in whether you are watching entertainment or an election campaign.

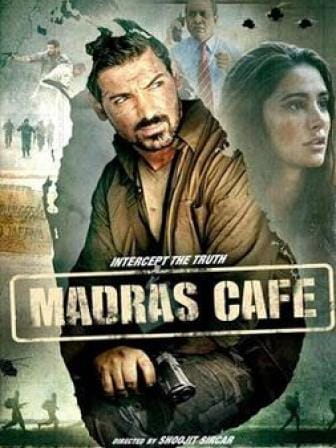

The easiest way to spot propaganda on screen is to notice who is being saved, and from whom. Every story needs a villain, and Bollywood has made an art out of villainising entire communities, ideologies, or centuries of history. In films like "The Kashmir Files" or "The Kerala Story", the narrative is not satisfied with exploring tragedy as it must assign guilt, draw blood, and wave a flag while doing it. They claim to be based on true story", but so do most fairy tales. The truth, in such cases, is less about facts and more about feelings; the kind of feelings that make people clap in theatres and seethe on social media. The packaging, of course, is patriotic. Consider "Madras Cafe". Ostensibly a political thriller about India's covert dealings in Sri Lanka, it wore the researcher's coat and won praise for restraint even as Tamil groups accused it of caricaturing insurgents and reconstituting complex violence into tidy patriotism. The film worked because it largely respected cinematic craft; its danger was not crude lies but selective emphases and excisions that made certain conclusions feel inevitable.

Then there are films that are less coy but more effective because they are emotionally dexterous. "Rang De Basanti" organised youth outrage into a cinematic narrative that made civic anger feel heroic and performative; its impact spilled beyond screens into public marches and moral conversation about corruption. The film did not spoonfeed doctrine; it anthropomorphised a political awakening, which made its persuasion feel like a personal epiphany rather than an instruction manual. That is the point: persuasion that feels volunteered is far harder to interrogate. Some movies wear national pride like a coat of arms. For example, "Uri: The Surgical Strike" refused to call itself propaganda; it called itself inspirational. But inspiration is a slippery thing when the film ends up sounding like a government slogan. Patriotism sells, and Bollywood knows its best-selling products rarely come with disclaimers.

Hindi cinema has plenty of nuanced cases that complicate the binary of propaganda versus art. "Raajneeti" staged politics as Greek tragedy: the family becomes a state, and vice versa, inviting viewers to see corruption as spectacle rather than policy. "Madras Cafe" posed ambiguity while still attracting heat for its representation. The lesson here is that subtlety is not the absence of intent.

For decades, powerful states have used cinema as soft power, and Hollywood practically wrote the manual. During World War II, American studios churned out films glorifying the Allied cause, sometimes with the direct involvement of the Pentagon. "Top Gun" was so effective at boosting military recruitment that the U.S. Navy famously set up booths outside theatres. Decades later, "American Sniper" turned complex geopolitics into a morality play about one man's courage, making war look less like horror and more like a personal brand opportunity. Russia, too, has its cinematic soldiers with films like "Panfilov's 28 Men" or "T-34" recast Soviet heroism as a near-religious experience. Every nation that fancies itself as exceptional eventually turns to the camera for validation.

Looking back at history, D.W. Griffith's "The Birth of a Nation" remade public opinion about Reconstruction and did real harm by romanticising racist violence; its release correlated with an ugly spike in racial violence, an early demonstration of cinema's capacity to shape social action. Leni Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will" remains a technical masterclass in image-making and a case study in how aesthetic splendour can lend moral credibility to authoritarianism. More recently, China's "The Battle at Lake Changjin" became one of the highest-grossing films in its history, telling the story of Chinese soldiers defeating Americans in Korea with divine-like bravery. It was co-produced by the army and released around the Chinese Communist Party's centenary, which of course is pure coincidence. Across the world, nations have realised that cinema can achieve what censorship cannot: persuasion through beauty. So, why suppress dissent when you can drown it in spectacle? The filmmakers call it courage. Critics call it confirmation bias with better cinematography.

Even Bangladesh is not immune to this phenomenon. Recent biopics and documentaries about national leaders crystallise state narratives into celluloid hagiography. "Mujib: The Making of a Nation", directed by Shyam Benegal and released amid carefully staged screenings and institutional promotion, was treated by many as a national event where memory management met mass entertainment. "Hasina: A Daughter's Tale" offers another, more intimate example of how documentary form can be used to consolidate personal and political narratives. When governments endorse or help produce films about their founding figures, the fence between national memory and national messaging becomes porous. Propaganda thrives because it speaks in emotions, not arguments. A two-minute monologue can undo years of academic nuance and a swelling background score can override doubt.

The danger, however, is not only in what these films say but in what they simplify. Complex histories become binary conflicts; messy social realities get rewritten as morality plays. It is easy, after all, to love your country when the camera zooms in on a waving flag and fades out before the first uncomfortable question. And it is not just religious politics as sometimes the propaganda is subtler, dressed in the language of national pride, technological progress, or social unity. The problem is not that films love their countries. The problem is that they increasingly love their governments too. So, a film that questions authority is considered anti-national. One that flatters it is historic. Everyone gets the cinema they deserve, and lately, we seem to deserve lectures disguised as entertainment.

The line between art and propaganda is never just drawn by the artist, but by the one who pays for the paint. The more these films claim to speak truth to power, the clearer it becomes that they were funded by it. What used to be state censorship has evolved into state sponsorship. In some ways, it is more efficient because why would you ban what you can bankroll? A good propaganda film does not shout; it sentimentalises. It wraps exclusion in emotional music and close-up tears, convincing you that intolerance is just another form of devotion. And in a world where attention is currency, outrage is the best marketing strategy. The result is a cinematic landscape where truth is optional, but feelings are mandatory. Because if you can get people to feel before they think, you have stopped being told a story and started being mobilised.

Of course, there is nothing new about political cinema. Art has always taken sides. But the best political films question power; propaganda films serve it. One challenges; the other comforts. And somewhere along the way, we stopped wanting to be challenged. We just wanted to feel righteous for two hours, and maybe buy popcorn with a discount coupon from a state-sponsored screening. The irony is that the most dangerous propaganda films rarely announce themselves as such. They arrive wrapped in tricolour, scored with swelling violins, insisting they are just showing the real story. Maybe "The Taj Story" will be another one of these, but the bigger story is not about any one film. It is about a cinema culture that increasingly confuses emotion for evidence and applause for truth. And while cinema may not rewrite history, it certainly reshoots it — in 4K, with patriotic subtitles.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments