Miyazaki, AI, and the weight of human ingenuity in art

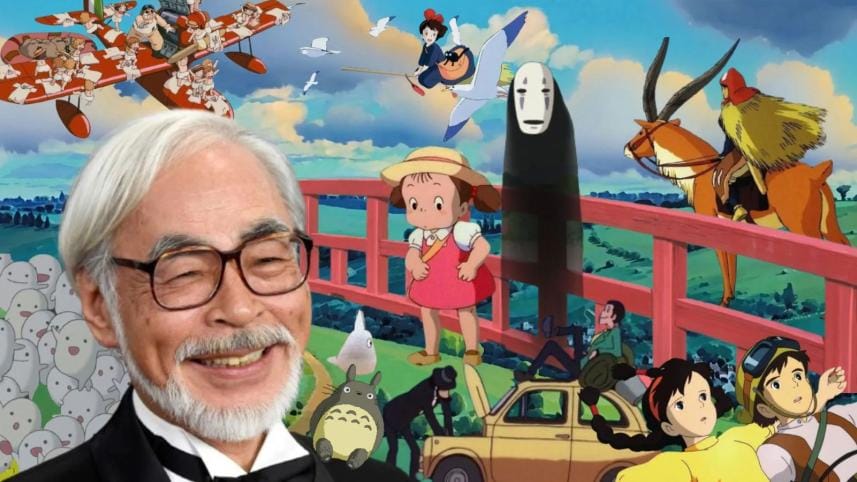

One ought to adhere to a certain level of reverence when talking about Hayao Miyazaki. The man has dedicated his life to a form of animation that values patience over production speed, detail over efficiency, and emotion over mere aesthetics. Back in 2016, he made a public statement regarding AI-generated art, where he called it an "insult to life itself". To therefore understand the weight of the proclamation itself is to understand the nature of his art.

His films are not merely images strung together; they are living, breathing worlds. Every flickering lantern in "Spirited Away", every ripple on the water in "Ponyo", and every rustling leaf in "My Neighbor Totoro"— are crafted with purpose, with the human touch that AI can never replicate. And yet, here we are. Just days after OpenAI unveiled its most advanced image generator, social media has been awash with AI-generated images mimicking the Studio Ghibli aesthetic. Some find it delightful, a demonstration of how powerful this technology has become. Others, perhaps those who have spent their lives immersed in true artistry, recognise it for what it is—a grim reflection of our era's obsession with convenience over craftsmanship, automation over authenticity.

Using AI to create a Ghibli-style image of yourself may seem harmless, like yet another passing trend. However, to Hayao Miyazaki, who spent decades pouring his soul into his work, watching his art be reduced to a mere algorithmic output is a gutting betrayal of everything he stands for. This is not simply an artistic trend but a blatant, unpaid imitation of something authentic, something humane. Even worse, it is being done without his permission, without credit, and without the respect that a creator of his stature deserves. It does not matter if the images are cute or aesthetically pleasing; if you care about art, then you must care about how it is made. To engage with AI-generated art as if it were genuine art is, at its core, an act of unethical consumption.

When we watch an AI-generated "Ghibli" scene, we are not engaging with a human's labour, intent, or soul. We are engaging with mimicry, a hollow imitation that demands nothing from the creator because there was no creator. The idea of art, in the classical sense, hinges on human experience, effort, and interpretation. When we reduce it to an algorithm's regurgitation of existing styles, we strip art of what makes it meaningful. The consumption of AI-generated art, then, is not ethically neutral. It is an act that erodes the value of real artistry, shifting the balance of power away from creators and toward corporations that own the datasets these AI models are trained on. It is not just the art that suffers, but the artists themselves.

Imitation, in human hands, is a form of learning, an apprentice copying the strokes of a master. In an AI's hands, it is extraction. AI does not learn in the way an artist does—it steals. It scrapes data, absorbs existing works without permission, and then repackages them in a way that is passable enough to fool an untrained eye. The result is a kind of mass-produced, soulless imitation that, while momentarily aesthetically pleasing, lacks the imperfections and intentions that make human art worthwhile. This is particularly insidious in the case of Studio Ghibli. Miyazaki's work is not simply about style but philosophy. His films are infused with pacifism, environmentalism, and an understanding of the natural world that AI cannot comprehend. When we see an AI-generated image of a politician or a meme in "Ghibli style," it is not just an aesthetic choice—it is a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes Ghibli, Ghibli.

The shift from human-made art to AI-generated art is not just a shift in medium but one in power. Art has always been a form of resistance, a way for individuals to express themselves in ways that disrupt, challenge, or redefine culture. AI art, by contrast, exists purely as a tool for those who control it, without any struggling animators spending years refining their craft. There is only the corporation that owns the model, the dataset that was fed into it, and the users who prompt it with requests. The idea of the "artist" is removed from the equation entirely, replaced by an algorithm that exists to replicate and reproduce. And with this shift comes an economic reality that is just as troubling as the ethical one. Why pay an artist when you can generate an image in seconds? Why hire illustrators when you can prompt an AI? This is not progress but a devaluation of artistry itself.

Ironically, one of the central themes in Miyazaki's work, environmentalism, is directly threatened by the very AI-generated images that now seek to imitate his art. Training AI models is not an eco-friendly process. It requires massive computational resources, consuming energy at a scale that is invisible to the average user. The same corporations that produce these AI models, the ones claiming to democratise art, are also some of the biggest contributors to carbon emissions through their data centers. In contrast, Miyazaki's work is rooted in the natural world. His films warn against the dangers of unchecked industrialisation, of human hubris in the face of nature. The irony, then, is almost poetic. AI-generated Ghibli art is, in many ways, the very thing his films warn us about. It is industrialisation masquerading as creativity, automation masquerading as artistry.

Defenders of AI-generated art argue that this is just the natural progression of technology and that new art forms build upon what came before. But there is a difference between innovation and erosion. Photography did not replace painting; it expanded what art form is. Digital tools do not kill traditional animation; they enhance it. AI, on the other hand, does not create a new medium; it replaces the artist entirely. And in doing so, it erases the very thing that makes art human. When we replace human artists with AI, we are not just streamlining the creative process; we are fundamentally altering what art is. We are shifting from a culture of creation to a culture of consumption, from a world where art is made to a world where it is simply generated. And by doing this we are not just disrespecting Miyazaki but art itself.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments