Bazaira Vasha: Dhakaiya Sobbasi and their language

When Subahdar of Bengal, Islam Khan Chishti, entered Dhaka in 1608 or 1610, he was accompanied by a diverse group of North and North-West Indians, Afghans, Iranians, Arabs, and other foreign Muslims and Hindus. This influx of migrants continued for nearly 250 years. Many of them settled along the banks of the Buriganga River, in what is now Old Dhaka, and their descendants form the core of its original population.

From around 1610 onwards, a unique mixed language began to develop among these families — an amalgamation of Arabic, English, Gujarati, Turkish, Pali, Portuguese, French, Persian, Munda, Sanskrit, Bengali, and Hindustani (Urdu and Hindi). This creolised tongue became the regional spoken language of Dhaka's original inhabitants. Even today, many native families in Old Dhaka continue to use this language in their homes, communities, markets, and social gatherings.

However, the exact number of speakers has never been officially documented — perhaps because the language has not been taken seriously by scholars or authorities. Among the old Dhakaiyas, this linguistic tradition is now known as the 'Sobbasi' language, and its speakers identify themselves as Sobbas or Sobbasi. Today, Sobbasis reside in various neighbourhoods under Sutrapur, Kotwali, Bongshal, Chawkbazar, Lalbagh, and Hazaribagh thanas of Old Dhaka.

The term 'Sobbas' comes from 'Sukhbas', meaning to live happily, which evolved into 'Sokhbas' (happiness as 'sokh'), and finally 'Sobbas'. This linguistic shift mirrors other Dhakaiya transformations like 'Rai Saheb Bazar' to 'Rasabazar' or 'Takht' to 'Takta'.

One of the complexities of the Sobbasi language lies in the use of a-kar. There are two types of a-kar pronunciation: one with emphasis and another with a softer tone. For example, "cloud of sky" is expressed in Sobbasi as asmanka abar. In asmanka, each a-kar is pronounced with emphasis, while in abar, the a-kar is spoken softly. Those unfamiliar with the Sobbasi language may struggle with pronunciation due to this nuance. Sobbasis rarely use chandrabindu and tend to speak quickly — for instance, Chan Khar Pool becomes Changkhakapol. Similarly, u-kar, e-kar, and sh sounds are less used, with both sh and s typically pronounced as s.

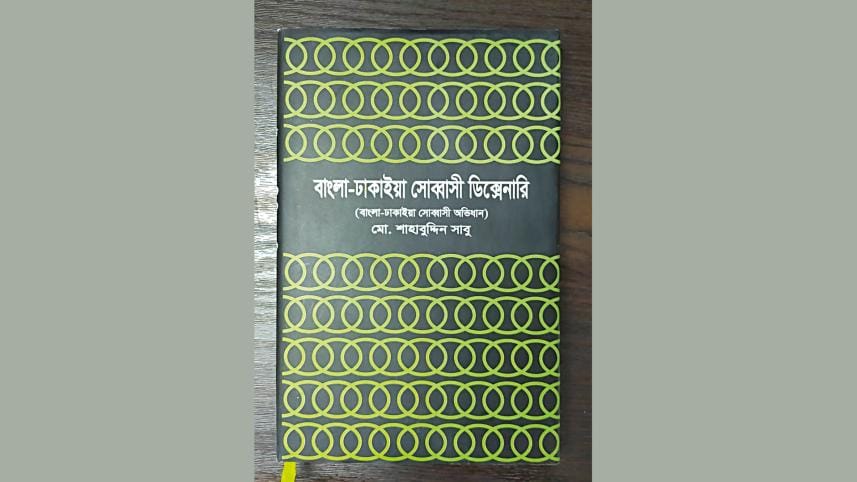

Although the Sobbasi language of Dhaka is a rich urban dialect, research on its origins is scarce due to the lack of written records. As a purely spoken language, it has been passed down orally through conversation, stories, rhymes, and proverbs. Traditionally unwritten, it has only recently begun to be documented using the Bengali script. Notably, the Bangla-Dhakaiya Sobbasi Dictionary was published on 15 January 2021, marking the first major effort to preserve and study this unique dialect.

Urdu expert Professor Kaniz-e-Batul notes that 18th-century Dhaka's rice trade brought together Bengali and Hindustani speaking Marwaris, shaping a mixed urban tongue that evolved into the Sobbasi dialect. Historian Sharif Uddin Ahmed adds that Hindustani—a blend of Hindi, Urdu, Persian, and Arabic—was the main conversational language in Dhaka. During the Mughal era, it served as the lingua franca across towns and cities, enabling communication among diverse communities.

The language of Old Dhaka is broadly divided into two types: the Sobbasi dialect and the Kutti dialect. Although both are urban dialects of Dhaka, they are distinctly different, with more differences than similarities in vocabulary and pronunciation.

For example:

Bengali: Kujor abar chit hoye ghumanor shokh.

Sobbasi: Kujaka Fer Chet Hoke Soneka Saokh.

Kutti: Gujarbi abar chit oya whiber sock.

Bengali: Kukurer pete ghee hojom hoy na.

Sobbasi: Kottaka Petme Ghi Hajam Hotani.

Kutti: Kuttar pete gi ojom ohe na.

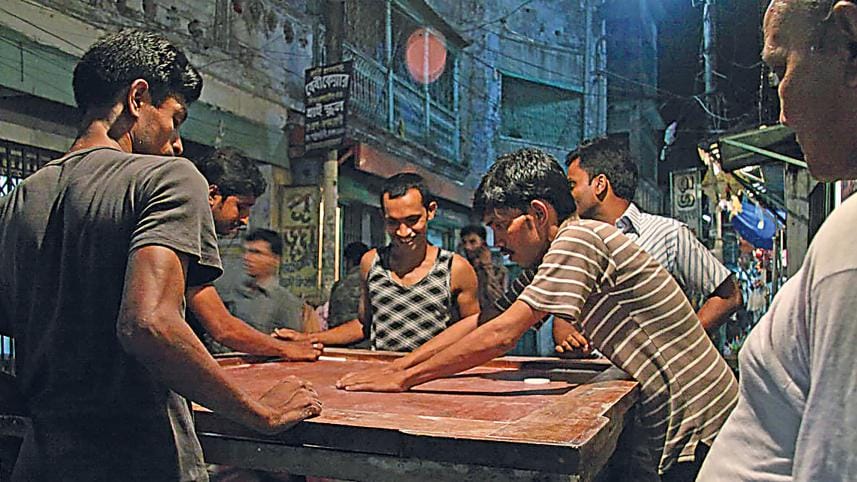

In 1838, James Taylor listed 162 occupations in Dhaka, each group speaking its own language. However, in markets and on the streets, Hindustani served as the common tongue. The Sobbasis were part of this multilingual population. Even today, Dhakaiya Kuttis refer to Hindustani as bazaira vasha, meaning "market language."

In early 19th-century Dhaka, the upper class spoke Persian, later shifting to authentic Urdu, which they continued using until 1971—and many still do. They excluded the Sobbasi dialect from their social circles. However, those unfamiliar with either authentic Urdu or the Dhakaiya Sobbasi dialect often find it difficult to tell them apart.

After 1947, the arrival of Urdu-speaking Muhajirs, or 'Biharis,' further influenced the Sobbasi language. This overlap has led to frequent confusion between the two speech forms, though they remain distinct.

Language is like water in a flowing river—it moves forward, carrying along whatever it encounters, with no turning back. In the Sobbasi dialect, new words are constantly being added while many old ones fade away. Still, it can be said that this urban dialect, now widely spoken among Old Dhakaiyas, began its journey with Hindustani in Dhaka around 1610. Over time, it has evolved under the influence of various languages and continues to thrive in the heart of the city.

Md. Sahabuddin Sabu is a researcher and the author of the Bangla-Dhakaiya Sobbasi Dictionary.

Comments