“A well-read woman is a dangerous creature”. Is she really?

"How did literature ruin you, btw?" reads the message on the screen, sending my stomach into a momentary frenzy of knots. My response to his text is reluctant but fluid, revolving primarily around the idea that being an avid lover of literature has rendered me 'undateable'—unfit for a patriarchal society.

I was telling my friend Tanvir about my woes in hetero-dating—about how the men I was talking to, whether reader or not themselves, seemed to be threatened by a woman who reads and chooses to identify as a feminist. I'm not trying to shift the entire blame on my reading habits (I am well aware that this is a joint effort of multiple flaws). However, I believe this is not just a me-problem. My belief is rooted largely in a massive surge of chauvinistic content my social media algorithms seem to have picked up on, coupled with my concerns for such a tragically controversial figure as Andrew Tate becoming a zeitgeist of present times. It concerns me that Tate's apologists range from impressionable boys in my grade 9 classroom to 30-something-year-old single dads. It concerns me that my own mother calls me a 'feminist' with such chagrin in her tone, it begins to feel like a slur.

Ironically, it was my strong-female-role-model of a mother who laid the footing for my feminist ideologies. However, it is when I started venturing out of my cocoon of YA and fantasy fiction during my late teens, turning towards classics such as Pride and Prejudice and Mrs. Dalloway that it slowly started to take a more concrete form.

In my 3rd year Literary Theory classroom at university, I had found myself a community of reading women who enjoyed the taste of the word 'feminist' rolling off their tongues. We revelled in discovering Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication and sought to embody the courage of this 18th century woman in our own writing. We marvelled at her daughter, Mary Shelley's rebellious streak. It made me look to my mother–a reader in her own right. I had seen her zealously referencing Samaresh Majumdar's Satkahon and its feminist heroine, Dipaboli, in multiple conversations with my aunts about books. I had heard stories of her hiding Masud Rana in the folds of her Bangla textbook in class. She had told me how she used to inhale her way through Humayun Ahmed books as soon as she could get her hands on one. It made me wonder why I know these facts about her in the form of stories, having never seen her actually get lost in a book as I did. When I asked her, she told me, in Bangla, "It's not possible to be a reader anymore once you're a married woman."

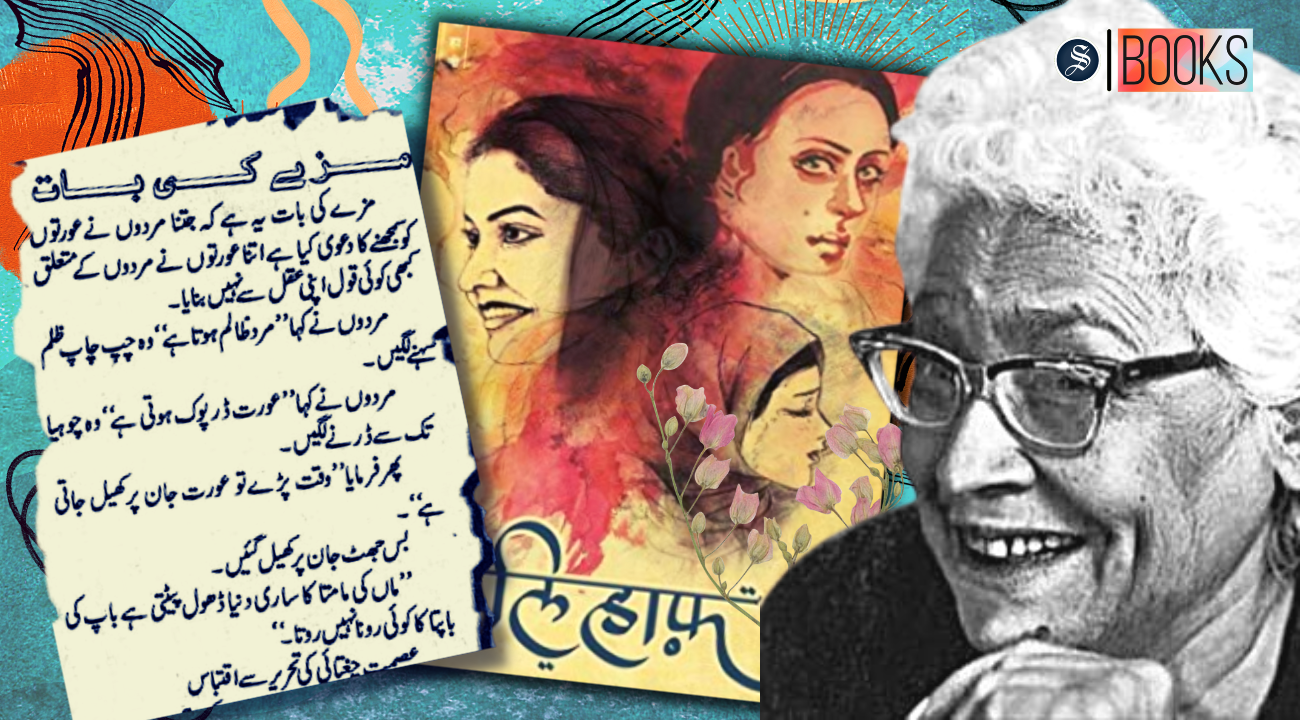

The contradicting natures of my mother and my experiences in trying to establish relationships with men got me thinking of a quote I had seen on countless pop-arty graphics on Pinterest or on the Facebook cover photo of the reading millennial woman or in Instagram captions under portraits taken at photogenic book cafes. "A well-read woman is a dangerous creature"—wrote Lisa Kleypas in one of her romance novels. It got me thinking about who a "well-read woman" even is and what being a "dangerous creature" even means. In search of an answer, I posted a story asking the female demographic of my Instagram followers how they felt about this quote.

Waziha Aziz, a fellow literature enthusiast and writer, defines a well-read person as "one who reads fearlessly and for the sake of knowledge." As for being dangerous, she enunciates, "We become dangerous when we pose a threat to something. And that can only happen when we take action. Reading is just a way to know that we NEED to take action, you know?"

My best friend, a teacher at the British Council and a voracious reader of the fantasy fiction genre, explains: "Reading gives us knowledge and knowledge is power. You know how most of the countries have education systems that are underfunded? It's because when you learn, you start questioning things. And they don't want you questioning the status quo."

As illuminating as these responses were, I felt the precedence for what counts as 'reading well' still remained ambiguous. Digging through Google search results for book titles that make one 'well-read,' I found classics to be the overarching motif across the listicles. The problem wasn't that the lists were Eurocentric or heteronormative or dominated by male authors—they were actually quite inclusive on these matters. However, genres that are composed of a predominantly female audience are often perceived as low in prestige. Let's compare the Percy Jackson series with the Lord of The Rings trilogy, or even the Harry Potter series. Tolkien's series holds a pioneering status in this genre, yet there is an imbalance of literary prestige between his scions. Personally, I attribute this to the demography of their audiences.

There is a certain prestige attached to books and movies, any cultural or recreational item really, that is accepted by boys and men. Whereas, when the target audience is mainly female, it is considered to be kitsch rather than an artform with cultural significance. It reminds me of Netflix's Joe Goldberg scoffing in the 4th season, "whodunit … the lowest form of literature"—and then going on to devour Christies to solve his own murder mystery. I think it is worth noting how Conan Doyle is considered a taste-maker by academia when it comes to crime thrillers and Christie remains pulp fiction.

On the other hand, when I contemplate women as 'dangers' (well-read or not), it makes me think back to my best friend telling me not to use the word 'threat' in the title, because it might anger a lot of readers. It reminds me of Carolyn Kizer writing in her poem 'Fearful Women': "Eve learned that learning was a dangerous thing / for her: no end of trouble would it bring." I am reminded of such giants in feminist poetry as Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath and what 'dangers' they posed to society in being who they were and writing about their vulnerabilities—their pained lives and more painful deaths. I am reminded of Dickens' Estella Havisham and Fitzgerald's Daisy Buchanan against Austen's Lizzie Bennet. Of Hermione Granger's frizzy hair from the books being turned to Emma Watson's flowing curls on the silver screen. And now I think, it is not the well-read woman, but the female gaze that can be a dangerous thing.

I am reminded once again, of my friend's text—of my response telling him, "I wish to remain blissfully ignorant."

So, I digress: our society is a threat to the well-read woman.

Tashfia Ahmed is an English teacher at Scholastica and an Instagram poet ghosting her followers. She requests that you fuel her vigour for writing by leaving her tasteful hate comments in her Instagram @tashfiarchy.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments