The untapped powers of Bengali folk horror

When I was a child, every night, I'd ask my parents to tell me a story when they tucked me into bed. From talking trees to scheming foxes, the mystical realm of Bengali folklore was a bottomless well from which my pre-adolescent mind drank with thirst. It led me to what can only be deemed as the Holy Grail of Bengali folklore: Thakurmar Jhuli (1907).

First published in 1907, the four lengthy volumes anthologised mythological stories from all the corners of Bengal, by the late Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumdar. His three other volumes—Thakurdadar Jhuli (1909), Dadamashayer Thale (1913), and Thandidir Thale (1909)—all conjure a similarly homely atmosphere, in which children discover mysticism in Bengal through the stories of Lalkamal-Neelkamal, Heeramon, Kiranmala, and Rajkanya Kolaboti, narrated by grandparents.

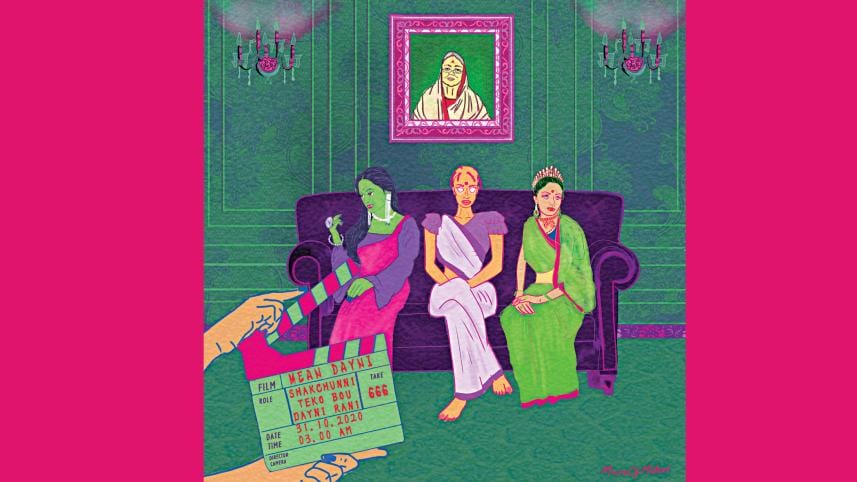

Those stories feel relatable, filling you with a sense of dread that somewhere, somehow, they are real. Yet the genre's biggest appeal lies in its political undercurrents. There are ghosts who reflect religious segregation—the Mamdo Bhoot and Djinn of the Muslim communities, the Shakchunni and Petni who terrorise Hindus; ghosts who illustrate the disturbing dominance of patriarchy in Bengal—Dainee and Pishachini; and classist monsters like Jokkho and Rakkhosh, who prey on beings inferior to them in both strength and stature. The stories ring with the trauma and regressive practices surrounding religious and class-based differences across the Bengali community, for which blood is spilled in the name of superficial purity. Ghosts appear as spirits of vengeance from horrible tragedies of gender-based violence, notably female infanticide and forced child marriage.

Many of us are also drawn to the aesthetics of it all. There is always the massive, near-palatial jomidarbari, the lavish and intricate décor in the halls within, and the inhabitants dressed with an old-world charm and elegance, all of which offer us Bengali readers a common ground rooted in colonial history, which we couldn't find in the Gothic novels set in the English countryside.

It is unfortunate that imported horror seems to have trumped all this beautiful, rich local produce. Bengali authors in the past have contributed generously to the preservation of Bengali folk horror in literature, such as in Konkal (1892), Goshaibaganer Bhoot (1979), Lal Chul. That legacy began to wane as the language and style became less comprehensible—too dense and tiresome—for audiences at home and abroad, but authors like Humayun Ahmed and Muhammad Zafar Iqbal retained the efforts of their predecessors with the Misir Ali series and short stories like O (2008) and Pishachini (1992). But while Anam Biswas's 2018 revival of Debi enjoyed both critical and audience acclaim, even that seemed to offer a lukewarm experience compared to the story originally penned by Ahmed.

Enter Netflix's Bulbbul (2020) and Typewriter (2019), inspired by Tagore and Satyajit Ray's Charulata (1964), Fritz, Nastanirh (1901), and Amazon Prime Video's Tumbbad (2018), a period horror about generations of men greedy for cursed inheritance.

As impressive as these efforts are, the problem with them is the same as that with Biswas's Debi, which is that they seem to have been adapted with insincerity, offering diluted story lines crammed with mythological references. The scale and content of this genre could have been phenomenal, given the platforms and resources at our disposal. Sadly, audiences with access to streaming platforms are only on the hunt for "binge-able" content these days, instead of insightful exploration.

Amidst the sea of Dracula spin-offs and Exorcist reboots—with more recent additions like Hill House (2018) or Bly Manor (2020)—the once-glimmering, marshy ghost-light of Bengali folk horror falters. But all it takes is a peek into the mystical realm inhabited by the likes of the fearsome Brahmodaittyo, and one can never look back.

Rasha Jameel studies microbiology while pursuing her passion for writing. Reach her at rasha.jameel@outlook.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments