“Sundarer Taane Mongol Shotru”: Not just a passion project

A narrow road amidst the greeneries of a quintessential country scene. A little boy, carried on the shoulders of his tutor, passes many a mile through these roads. He meets new people along the way and gets a taste of the hospitality that they offer.

Sundarer Taane Mongol Shotru (Srabon, 2021) starts on this wholesome note, where author Kapil Ghosh connects his childhood memories of visiting the Sundarbans to take a peek into the lives of the people of the region. In the process, he takes his readers through the local people's lifestyles, cultures, beliefs, history, and folklore. Nature plays a crucial part in these aspects of the region because of the inhabitants' dependency on it for their lives and livelihoods.

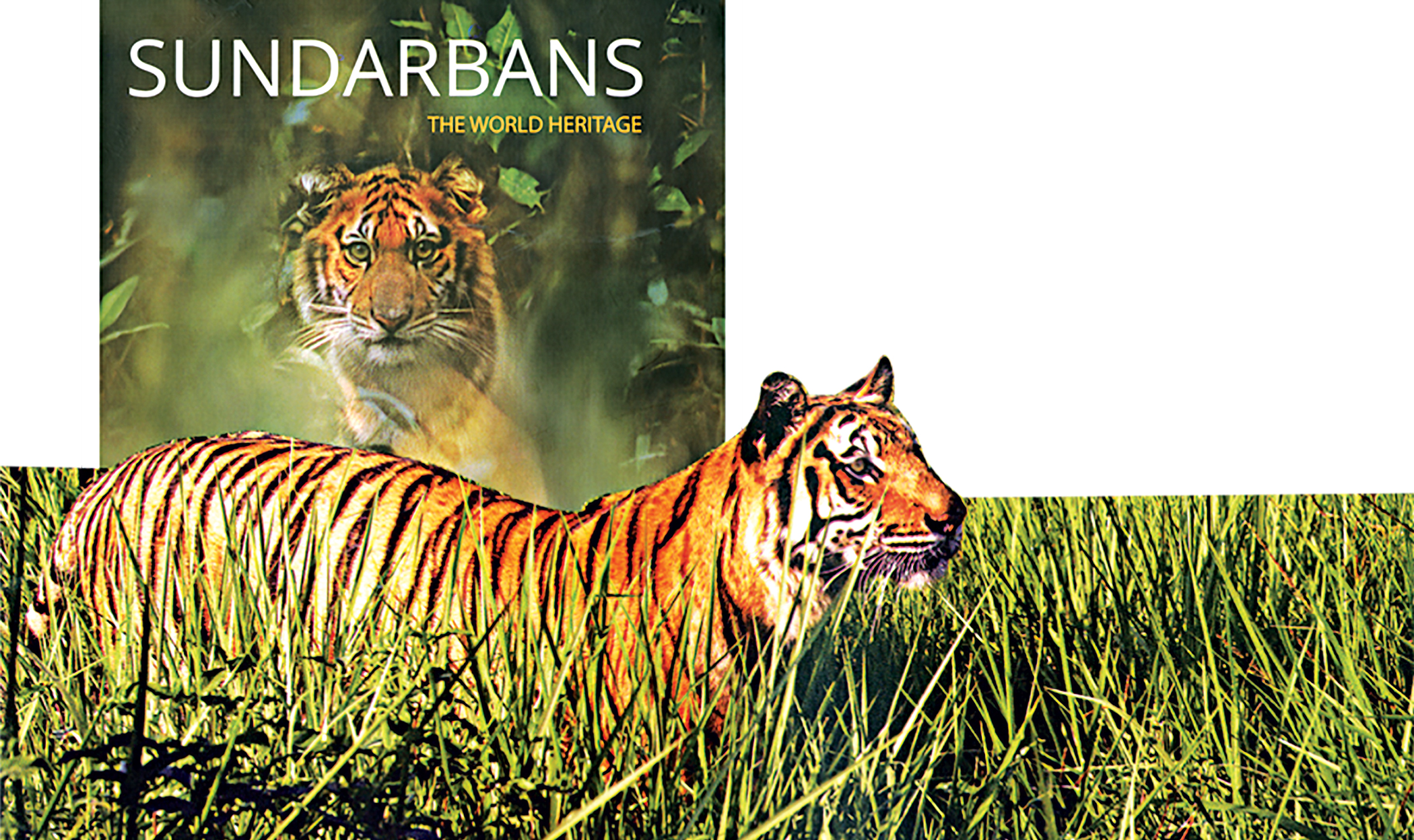

The simplicity with which the people of the Sundarbans live is reflected in the interactions that occur between the writer and his tutor, Dipu Pandit, with whom he goes to visit the place. Upon entering Dipu's maternal village, they are met by a simple yet warm reception by the family. However, they are also forewarned: the people of the region never refer to the Royal Bengal Tigers merely as "tigers". Instead, they are nicknamed "Mama", which is how people address their maternal uncles in Bangla.

The boundaries of the village area are surrounded by a fence of trees that are locally known as "Babla trees" to prevent the tigers from entering the locality. In that vicinity, no one points to anything with their fingers, and raising one's voice is strongly discouraged, lest the "Mamas" become aware of their existence nearby.

The people of the region have their own version of worshipping mother nature as well. They are shown as ardent believers of Bonbibi—the Goddess of the forest—and are extremely cautious in their day-to-day activities so as not to anger her.

These seemingly fantastical anecdotes noted throughout the book are told by the locals with utmost conviction and faith, oftentimes connecting with their lived realities. The overarching narrative follows a stream of consciousness style of narration through these stories and the writer keeps the details intact in his recounting of them.

It allows us readers glimpses into the lives and psyches of the storytellers. However, these instances can come off as out of context at times—jumping from one timeline to another, without adding much value to the narration process or making it coherent.

Interestingly though, when it comes to the beliefs of treating the tigers with respect and faith in Bonbibi, the boundaries and divisions of religion are erased. Puthipath—an event rooted in local tradition—involves the recitation of Bonbibi's stories of wrath and grace, followed by Puja offerings; it is widely observed by both Hindus and Muslims. This intermingling of religions—wherein people commit to different faiths and still come together for a common set of beliefs—is what sets the people of the Sundarbans apart.

Rituals in a Puthipath also indicate the wide range of folk literature that originated from the Sundarbans. Author Kapil Ghosh makes it more evident when connecting his childhood memories of visiting the Sundarbans with the ones he, later on, made as an adult. He discovered poets, writers, and singer-songwriters on his journeys who had dedicated their lives to the mission of preserving and enriching the preexisting folk literature of the region. In the process of accommodating their works in the book, he also describes their perils in life— of being neglected along with their art. The author also describes in his writing the musings of these artists, a lot of which are intertwined with their lives in the Sundarbans.

Over the turn of pages, readers will realise how the Sundarbans have become a muse for the author from being just a mere passion project of documenting the lives of the region's people. However, as mentioned, a lack of coherence can be felt in the different sections of the book. This might be because a wide array of topics like songs, poems, and stories, the locals' accounts of the 1971 war, and even the author's own memories of the place, and fictionalised accounts, have been attempted to be covered, without one having much connection with the other, besides their geographic common ground.

This, however, doesn't take away the book's appeal as an informative piece of documentation. A nonfiction, mixed with fictionalised accounts of true events—the disarray rather brings to the table its own charm, offering much to readers who are interested to know more about the ways of and life in the Sundarbans.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a sub editor at the metro desk, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments