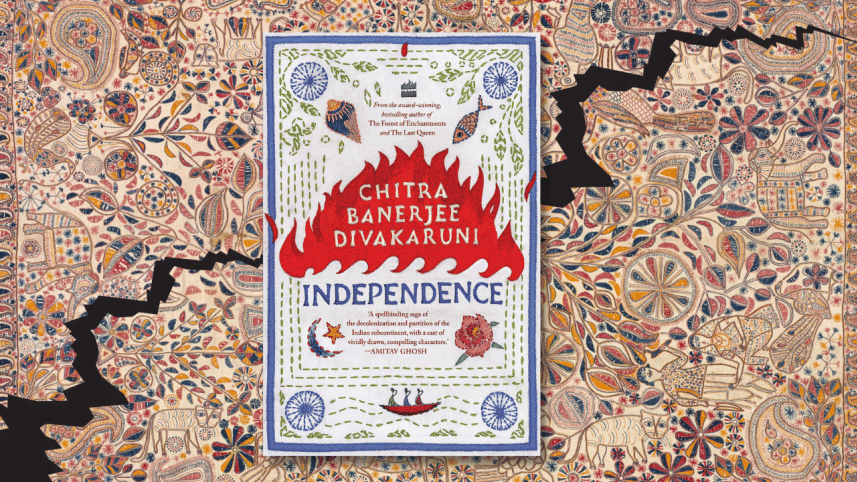

'Independence': A painfully poignant Partition story

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni has been telling the tales of women—independent and strong, flawed and humane—for a long time now, and Independence is no aberration from that normative style of hers. Set primarily during the tumultuous times of the Great Calcutta Killings of 1946, Independence tells the stories of three sisters, of the people they love and are loved by, of their trials and tribulations, their hopes and aspirations, and their ultimate loss and gain.

This book, though, is not merely a tale of the inner lives of three sisters, it is historical fiction with a delicate mixture of fact, where the Partition of India with all its bloody repercussions on the lives of people living in the fringes takes centre stage.

Independence tells the stories of Priya, Deepa, and Jamini; three daughters of the inordinately benevolent doctor Nabakumar Ganguly. Jamini is the archetypal village woman who does not want to break societal norms and on the other hand, Priya is the farthest from that archetype. She is the strongest of the three sisters and the soul, the rebellious voice of the novel. Fused with love, compassion and yearning for liberation and independence, Priya embodies a fiercely independent woman. Deepa is somewhere between these two, sometimes more like Priya than her other younger sister Jamini.

Divakaruni's prose is highly descriptive. She has a large repertoire of lush words to paint a scene like an artist painting a portrait of a lady, with incredible details to portray even the tiniest wrinkles of her face. She does not write sentences with clause after clause piled with one another like Gabo or Rushdie. Her sentences, rather, are terse and beautiful.

Yet the prose fails to compensate for the bleakness of her narrative. Her story does not offer a great deal out of the ordinary.

While it is true that the Bengali society in the mid-20th century was going through a massive societal upheaval, the opportunities given to women compared to that of men were still not something to be proud of. Perhaps they still are not. But such feminist retellings of the past are necessary in building a better and equal society. Divakaruni's protagonists are often flawed, have travails to tackle imposed by the patriarchal society, but it is the courage of their voices that makes us hope for a better future, where women will not have to go to implausible lengths to attain success in life, success which a man can attain with comparably less travails.

Divakaruni has a message to send with this novel. To her, independence entails not just liberation or freedom from subjugation, it also means doing the right thing for oneself and for the people around us.

Her novel is full of verve and vivacious spirit which is so typical of Divakaruni and yet for all its lustre, it fails to deliver an extraordinary tale. Such beautiful writing could only have been complimented by a more meticulous, less dramatic, and perhaps less colourful narrative steeped in reality.

Erstwhile East and West Bengal today are separated into two entities; one is a country in itself, the other a part of a bigger country and both created on the fault lines of religion. We have a genealogical connection with our past. However uncomfortable and bloody it might have been, we have to be cognizant of the fact that we are the children of Partition and we have acted—to put it very mildly—not nicely, when we were thrown into an us vs them dichotomy.

As long as there remains a gulf, a chasm between and amongst people, the perennial question will remain—was Partition the price of independence, or was independence the price of Partition?

Najmus Sakib considers himself the protagonist of Dostoevsky's White Nights. Reach him on Twitter at @sakib221b.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments