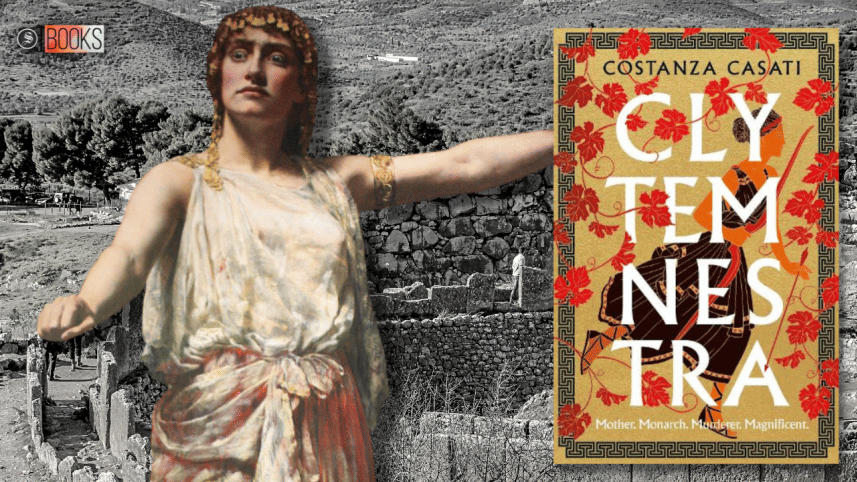

A gripping portrayal of one of Greek mythology’s most strong-willed women

One of the most controversial figures in Greek mythology is Clytemnestra, a Spartan princess and the queen of Mycenae. Despite being antagonised by many and sympathised by few, her dominance and influence remain uncontested. Costanza Casati's latest novel, titled after its heroine, provides a dynamic and complex portrayal of the queen. Known for her strong-willed, ambitious, and calculating nature, Clytemnestra is written as a layered, multi-faceted human being.

As the oldest daughter and the favourite child of Tyndareus, the King of Sparta, Clytemnestra is spirited, sharp, and unyielding. She is devoted to her family and fiercely protective of her sister, Helen. She also lacks the general bashfulness and prudishness associated with "good" women, exceeding expectations while still having to yield to the societal situations and decorums restraining women. Her lack of regard for rules makes her reckless, yet admirable.

Divided into five parts, the novel focuses on different phases of Clytemnestra's life. The first part opens with a teenage Clytemnestra hunting down a lynx, drawing light on her upbringing being equal to that of her brothers. She is shown to be lively, quick, and courageous; almost to a fault. Clytemnestra's rearing influences her decisions and actions throughout the novel. We learn of Clytemnestra's first marriage to Tantalus, the King of Maeonia, in this retelling. It is almost as if he is written as an antithesis to Agamemnon, Clytemnestra's second husband, who is introduced in the second part alongside his brother, Menelaus.

Throughout the rest of the parts, we observe her as an able ruler of Mycenae while her husband fights the Trojan War. As readers, we also witness her ferocities that are little associated with the common understanding of a "just" ruler. We see her as a loving mother, while also finding the fallibilities of motherhood flawlessly seamed into the storytelling.

Is Casati's take on Clytemnestra a feminist portrayal? Yes, it is as authentic a feminist portrayal as it can get, because it is not impossibly idealistic. Throughout the novel, we witness Clytemnestra's fortitude not to bend to patriarchal dominations and machinations, despite having to often submit. She uses her position to protect women and admonish those who have chosen to make her an enemy. We see her falter and accept the need for patience, tolerance, and compromises in certain circumstances. Through Clytemnestra's eyes, we see some of the women of Greek mythology and sympathise with them. The woman we find the most perspective on is Helen, later the queen of Sparta. While much of Greek mythology focuses on Helen's unparalleled beauty and her abduction/elopement, here Casati fleshes out Helen's character further and scrutinises her motivations behind the actions that shape Greek mythology.

The book spans over 400 pages and, not once becomes tedious or superfluous. However, the fast-paced nature of the text takes away from the gravity of certain situations, which with richer details, could have had a lasting impact. While the story itself stands to be memorable, the abrupt nature of the climax leaves little room for afterthought. Nevertheless, despite the novel being an easy read, Casati does a brilliant job of tackling the cultural differences between Sparta and Mycenae, especially when it comes to the treatment of women. From a teenage huntress to an able ruler of Mycenae, from a loving mother to a murderer, we see all the facets of Clytemnestra's personality probed to the core.

Yet the novel isn't just engaging on its own. It also provides a successful dose of retelling that Greek mythology enthusiasts will likely enjoy. It is safe to say that Casati's debut novel shows promise and leaves more to be anticipated.

Aysha Zaheen is an Economics graduate trying to get back into reading and writing.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments