Books that changed the world: Gilgamesh through the sands of time

My earliest brush with the world of Gilgamesh stems from a now hazy memory of a story telling session. It was a particularly hot Friday afternoon and I had just returned home from a trip to Neelkhet. Halfway through my grade-one history homework, my mother, whilst fanning herself with a 100 taka piece Shanonda magazine, told me the story of how Prophet Noah's story of the ark and the flood which led humanity to non-existence predates the Abrahamic religions. She went on to claim how, "We live to tell the same stories over and over again".

Unlike the blind, brilliant bard who is thought to have conceived Iliad and Odyssey. or Ved Vyas who put the tale of Mahabharata on paper with the help of a potbellied deity, and unlike, also, Virgil's journey of oscillating between a tortured artist and corporate parrot in The Aeneid, there are no fabled traces of the artist behind Gilgamesh. Yet the text itself stands tall as a myth and seems to almost shed the need for a solitary author. Michael Schmidt, the author of Gilgamesh: The Life of a Poem (Princeton University Press, 2019), has said in an interview that, "Gilgamesh is made by a river, by fire, by generations of scribes, by shepherds, ruin-robbers, archaeologists and scholars. In all the debris there are literally no vestiges of an identifiable poet to be found."

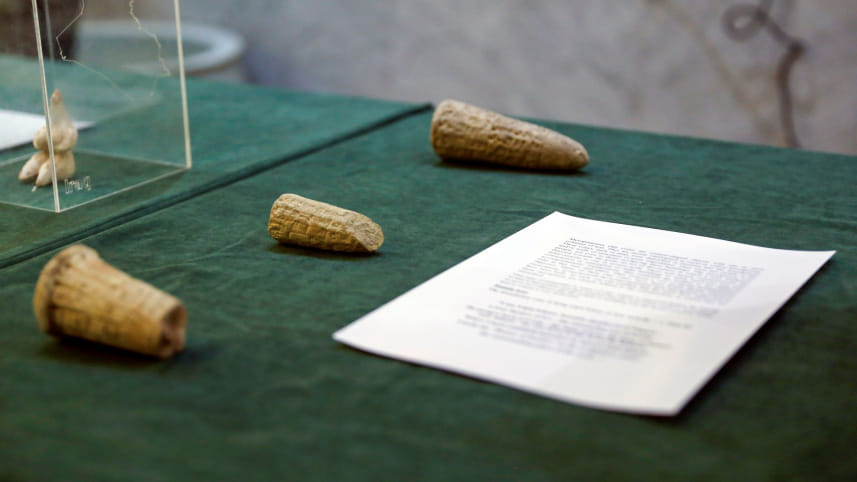

The epic antedates even the depiction of the famous Trojan war; it is, in effect, the oldest epic found till date. Originating as a series of five Sumerian poems about the adventures of the mythological hero Gilgamesh, the "Epic of Gilgamesh" was sewn together into a 12-tablet Akkadian language epic—decades, or even centuries, later. Most of the Gilgamesh poems were written down in the first centuries of the second millennium BC. The most complete edition comes from the 7th century library of Assurbanipal, antiquary and last king of the Assyrian Empire. The debris of the poem were first discovered in the mid-1800s by two Englishmen when archaeologists began uncovering the buried cities of the Middle-East. Since then, scholars and archeologists have been labouring to put the shards together and tie it into a unified whole—a tale of adventure, of morality and tragedy. The main body of the Assyrian epic has not been altered in essentials since the mammoth publications of the text, accompanied with commentary by Campbell Thompson, around 1930.

Its story tells of how Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk (present day Iraq), battles with and later befriends a giant by the name of Enkidu. They then feud with the gods causing Enkidu to lose his life and Gilgamesh to embark upon a quest to conquer death.

As time went by, wars buried the Assurbanipal library completely. Historians assume that the Babylonian gods and their universes went underground only to reappear in later Mediterranean religions and the heroes transformed and survived travelling westwards as well as to the east. NK Sanders, in the introduction of the pocketbook edition of the epic, writes— "Although the Sumerian hero is not an older Odysseus, nor Heracles, nor Samson, nor Dermot, nor Gawain, yet it is possible that none of these would be remembered in the way he is if the story of Gilgamesh had never been told." This implies that the epic has resurfaced through time in various ways, sometimes quite literally and at others, through known tropes and similar narrative plot lines. The fragmented tablets of this ancient poesy are still frozen in fluidity, perhaps still seeking its next puzzle piece.

The final sections of the tale finds Gilgamesh, desolate in the grief of his dead friend Enkidu, and nowhere near to defeating mortality. After returning to Uruk, the sight of the colossal walls of his city incites him to stand in awe at this enduring work of mortal men. And suddenly the readers are back to where they started, too, admiring the prosaic excellence of the city walls. The implication is obvious—that mortals can achieve immortality only through dazzling creations and art which will stand tall through the passage of time, unlike fragile, perishable physical bodies; that is the knowledge that Gilgamesh gets in his conquest to defeat death.

A few weeks ago, news headlines announced that a 3,500-year-old "Dream Tablet"—a 5 by 6 inches section of the epic that recounts Gilgamesh describing his dreams to his mother, who then labels it as premonitions of the arrival of a new friend—was returned to Iraq after being stolen during the 1991 Gulf War and illegally imported to London and finally the United States. It is one of 17,000 stolen antiquities being returned by the US to Iraq.

One can't help but juxtapose this story of loot and the tablet returning home to Gilgamesh's own journey against the ticking clock. The clay tablet, like the wounded hero himself, has come back full circle after weathering through terrible wars during the US invasions and attempted erasure by Islamic militants. Here we have an ancient trail of narration that has quite factually survived the test of time, existing in fragmented echoes of engraved cuneiform; existing, despite the changing topography of the world and despite being dispersed in a wide strip from Turkey to Iraq; existing, despite being written, composed and recomposed, reformed and transformed over a period of more than a thousand years. The tale of it spreading and resurfacing and moving from one time zone to another, from one space to another, is strangely synonymous to the ethos of the epic itself.

Through Enkidu's sexual relationship with the "harlot" in the initial sections of the story and his rejection from the natural world after that, we are reminded of Adam and Eve's fall from grace after the consumption of the fruit of desire and knowledge. While Enkidu symbolizes the raw innocence of nature, Gilgamesh symbolizes the pride of civilization; a dichotomy that has been explored rigorously in literature and art—especially in this day and age of Ecocritical and Posthumanist discourse. There is, also, the numbing depiction of love and loss in Enkidu and Gilgamesh's homoerotic friendship, and Gilgamesh's despair and anxious desire to defeat death is a yearning entrenched within all of us. Reading the epic reminds us time and time again that though at this day in time, our universes may seem infinitely larger, it still ends in abyss, the darkness mocks our ignorance and in the end we come back to the same point from which we set out, just like Gilgamesh—a king terrified of dying, coming to knock at the doors of eternal, evergreen poetry.

Jahanara Tariq is a postgraduate student of English Literature. She often finds herself praying to Tagore and Woolf on desolate mornings while chugging espressos and listening to Vivaldi's Winter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments