Revisiting the lost Jewish communities of Baghdad

Iraq once boasted one of the world's oldest Jewish communities, encompassing 2,600 years of rich cultural history punctuated with moments of benign tolerance, blatant discrimination, and outright intolerance and persecution. As the cradle of civilisation and a melting pot of different ethnicities and religions, one-third of Baghdad is said to have been Jewish, numbering 150,000 Jews, as recently as the 1950s. Yet there are four Jews remaining in modern day Iraq today. The Iraqi-Jewish diaspora, meanwhile, has gifted us luminaries such as the world renowned advertising executives, the Saatchi brothers; one of Singapore's founding fathers, David Marshall; as well as JFR Jacob, the Indian war hero of Bangladesh's Liberation War who authored Surrender at Dacca: Birth of a Nation (UPL, 1997), descended from Baghdadi-Jewish stock.

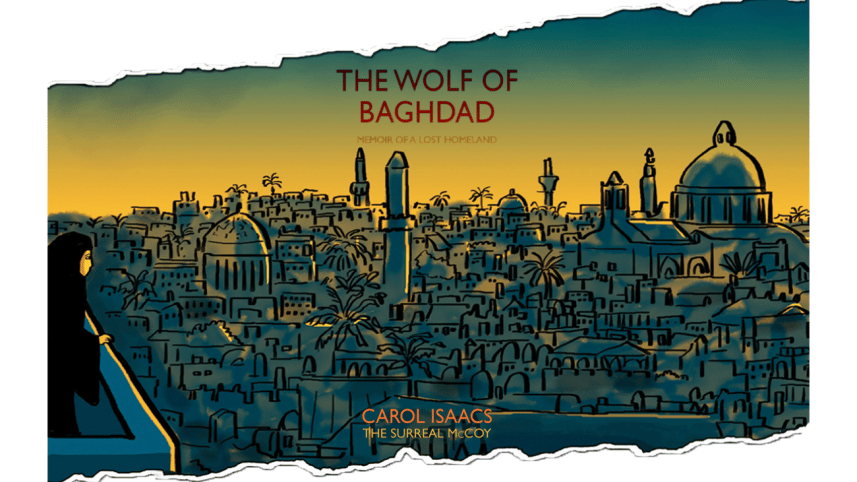

Carol Isaacs's masterful graphic novel, The Wolf of Baghdad: Memoir of a Lost Homeland (Myriad, 2020), takes us back to a time in the 20th century when Jews were an intrinsic part of Iraqi society. Its title is based on an Iraqi-Jewish tale that believes in the power of wolves to protect from demons. In fact, as was tradition, the cribs of children had amulets made of wolf teeth fixed to them to sway away dark spirits.

Isaacs taps into the memories of her family and friends who passed on their memories to her. The novel showcases the changes in 20th century Iraq, and with those changes, the Jewish community evolved from tradition to modernity, all the while placing strong emphasis on being both Jewish and Iraqi—two identities which have sadly been appropriated for chauvinistic nationalism. Isaacs recovers this history under the disguise of a black abaya, as was worn by her ancestors, walking in the narrow alleyways of Old Baghdad while evoking a strong sense of nostalgia and deep-rootedness with the land. The market places, mosques, synagogues, and buildings are all shown in thought provoking detail in the novel.

The pages are permeated by miniature portraits of the Isaacs and other Jewish families whose testimonials attest to the changing of times from good to bad to worst. The imagery reaches across time periods, but the peculiar and perhaps most engaging aspect of the narrative is that it has no dialogue. This silence seems to signal the widening gulf in the Iraqi-Jewish diaspora of the time, between their memories of belonging and the crude reality of an Iraq that never was.

These memories reveal what happened to the community in the midst of the Judeocide raging in WWII Europe. European anti-semitism seeped into the Arab world, creating pogroms, lynchings, and wide-spread destruction of Jewish life, spelling its end. All departments were purged of Jewish officials, anything resembling Judaism was buried underground, and Iraqi music, a great legacy that Carol Isaacs is the personification of, was systematically purged of its Jewish composers. Contrary to popular belief, it was the venom of European anti-semitism tinged with narrow-minded Arab nationalism that ended the vibrancy of Jewish life there.

A British author of Jewish Iraqi descent, Isaacs works as a cartoonist for The New Yorker under the name of The Surreal McCoy, and is an accomplished musician in her own right. She has never been to Iraq and like many refugees, the memories of her homeland linger in the music and stories passed down to her by the generation of yesteryears, the generation which saw the flourishing and destruction of one of the most conspicuously prosperous communities in the Middle East.

As history has always shown, hatred with one minority does not end with one; it amplifies and explodes. As Iraqi Christians and Yazidis flee and the Iraqi Sunni-Shia proxy war continues, the story of the Jews in Iraq remains a vital and important story of remembrance, of the reconciliation of memory and belonging.

Israr Hasan is a research assistant at BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments