The making of Bangladesh in the global sixties

"Mr Speaker Sir, what did Bangalee intend to achieve? What rights did Bangalee want to possess? We do not need to discuss and decide on them now [after independence]. [We] tried to press our demands after the so called 1947 independence. Each of our days and years with Pakistan was an episode of bloodied history; a record of struggle for our rights," said Tajuddin Ahmad on October 30, 1972 in the Constituent Assembly. He commented on the proposed draft constitution for Bangladesh, which was adopted on November 4, 1972.

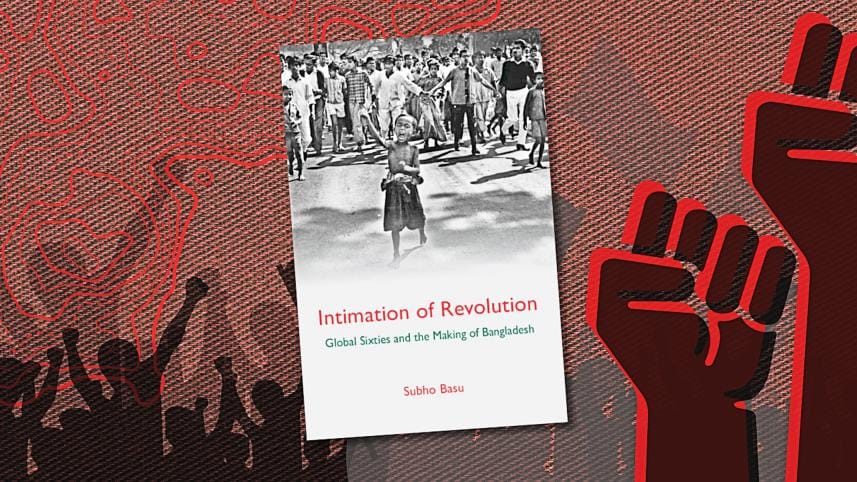

How did that struggle—which culminated in the creation of Bangladesh—shape a new nation state in the Global South? Who took it forward and in which way? How was it informed by events of the global sixties? Subho Basu's Intimation of Revolution: Global Sixties and the Making of Bangladesh maps out this fantastic history of the making of Bangladesh.

The development of the military establishment, suggests Basu, was directly sponsored by Western super powers, such as the UK or the US, who wanted Pakistan to be their client state.

Basu begins with two important post-1947 developments that brought about frustration among Muslims of then-East Bengal: the disintegration of the economy and lack of political representation. While the former led to an economic crisis, the second resulted in the development of a nationalist politics which was informed by Bangali nationalism. For Basu, the latter was a reactionary political doctrine developed out of a religio-political culture that considered the Muslims of East Bengal an "Other". As a result, a mass social movement was in embryo against that oppressive state in East Pakistan. He then explored the emergence of a colonial administrative state in Pakistan, which would be run by a military-bureaucratic government, depriving East Pakistanis of their desire for a state run by elected representatives.

As a result, they were against strengthening military establishments. The development of the military establishment, suggests Basu, was directly sponsored by Western super powers, such as the UK or the US, who wanted Pakistan to be their client state. In return, the military-bureaucratic regime received foreign aid to be used for development purposes. However, as the military establishment was grounded mostly in West Pakistan, the foreign aid was used there, depriving the East Pakistani masses of their economic prosperity. Consequently, nationalist politicians, such as Maulana Bhashani, opposed the Baghdad Pact—a military coalition led by the UK and USA. The skirmish between Bhashani and other Awami League leaders over the Baghdad Pact ended with the birth of a new political party, the NAP. Therefore, the political change or power sharing with the military establishment in East Pakistan was, Basu highlights, connected to global Cold War politics.

Basu eloquently details the emergence of a linguistic nationalism in East Pakistan in the third chapter. He attributes it to the Bangali poets and literati, through whose writings the idea of Bangali nationalism came about. In the high sixties, the ensuing "Bangali Renaissance", following a debate over the Bangla language, writing scripts, and state-sponsored ban on the songs of Rabindranath Tagore, inspired Bangali literati to write nationalist songs, poems, stories, novels, and drama that culminated in the emergence of a cultural identity of the Bangali speaking Muslims in Pakistan. Having been conscious about the Calcutta-based cultural domination, they used Arabic, Urdu, and Persian words in their new literature in order to craft a cultural tradition which would be different from both the North Indian Muslim and Calcutta-based Hindu traditions. In contrast, Pakistan witnessed the emergence of a garrisoned Islamic state under the patronage of the US during the military-bureaucratic regime of Ayub Khan. Basu highlights three developments during this regime: first, inequality in resource sharing and income gap between the two wings of Pakistan made the eastern part a colony of West Pakistani industrialists. Secondly, the introduction of basic democracy undermined all democratic processes, including the making of the constitution. Finally, there were state-sponsored programs to develop an Islamic nationalism that identified Pakistan a Muslim nation.

The three above-mentioned dimensions of the military-bureaucratic regime of Ayub Khan directed political courses in East Pakistan later, which Basu wonderfully narrates in the last two chapters of his monograph. Students were the vanguard of those exciting political upheavals. The students' movements, Basu emphasises, were informed by global anti-colonial and anti-imperial movements. He has highlighted the way in which iconic figures, such as Che Guevara, inspired students to take to the streets against the military regime. These two chapters are important to understand the diverse political strategies adopted by different political parties and the ways they were influenced by global Cold War politics. Basu has pointedly stated that although Bhashani initially called for an autonomy of East Pakistan, the six points demand of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman added a new vigour to that autonomy movement. The acceptance of the six points by students determined the courses of both the movements. Finally, the general election following the fall of Ayub Khan, the overwhelming victory of Awami League in the National and Provincial Assemblies, the failure of the military junta to transfer power to the elected representatives, and Mujib's firm determination toward autonomy accelerated the liberation of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

This book is an important contribution to the political history of South Asia, which connected the birth of Bangladesh to global Cold War policies. Particularly, this book is an excellent read to understand the way in which global or regional events in the high sixties informed political courses in Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. Moreover, it is an amazing work, which has connected local events to global and regional political developments and, therefore, will be useful for future historians to study the July 2024 uprising and the fall of the 'fascist' regime of Sheikh Hasina.

Anisur Rahman is a legal historian at Independent University, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments