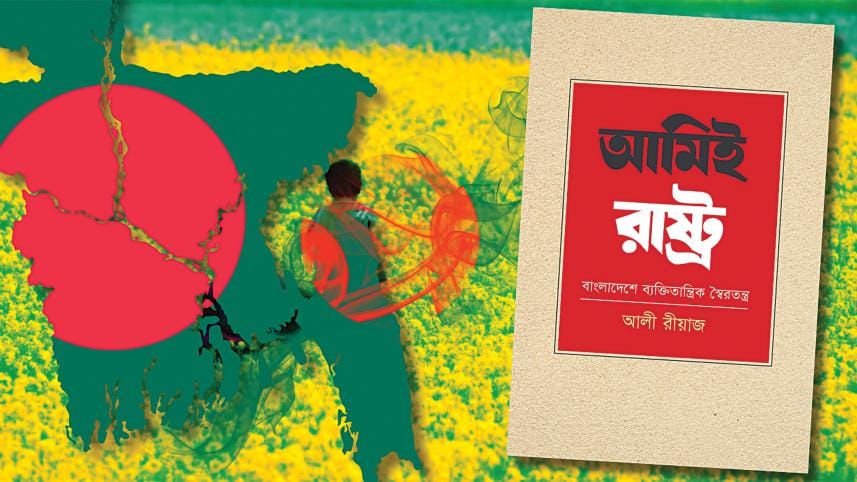

Personalistic authoritarianism and Bangladesh: Reading Ali Riaz’s ‘Ami E Rashtro’

Bangladesh has suffered the terrible luck of having to deal with authoritarianism several times since its inception, most recently under the Awami League from 2009 to 2024. Bangladesh is not alone, as the global trend at present seems to be sliding towards authoritarianism. These civilian-authoritarian regimes have fundamental differences with the brutal dictatorships of the past, which has forced citizens fighting for democracy to change their methods of protest. Ali Riaz, a prominent political scientist, lays out these discussions for general readers in his short book, Ami E Rashtro: Bangladesh E Byaktitantrik Shoirotontro.

The book has seven chapters in total, where the first four are an attempt to situate the authoritarian regimes in a global context, and the final three deal with Bangladesh specifically.

Ami E Rashtro begins with a brief introduction to personalistic authoritarianism, with examples such as Russia, China, and North Korea—where authoritarianism is not based on total brute force, but rather a cult of personality. The data Riaz presents illustrates how there is now a global trend towards authoritarianism, which has reversed the democratic wave that started in the 70s and continued after the Cold War ended.

The author analyses what could have led to this reversal. Academics have identified three types of causes—economic, politico-institutional, and social. The economic reasons involve economic decline and inequality which exists between the citizens of the country. Politico-institutional reasons refer to the weakening of institutions which are supposed to safeguard democracies, such as the judiciary, human rights, and anti-corruption organisations, etc. by political elites, and breakdown of the rule of law. Finally, the social reasons involve clashes between different ethnic or religious groups and class divisions in society.

Although these are integral to explaining the rise of authoritarianism, Riaz explains that what differentiates them from previous ones is the inclusion of another crucial element—ideology. Ideology, or a national story/myth is needed to legitimise all the shortcomings of the economy and the political system. The new authoritarians don't want to be seen as applying brute force in a military style; instead, they want to be perceived as democratic. This is why they utter phrases such as "democracy customised to local culture and heritage", which is nothing but a refusal to follow international standards.

Riaz also expands upon the process by which an authoritarian regime executes its will—democracy itself. By creating an ideological grounding, the would-be authoritarian claims to be the saviour of the nation and wins the parliament through majority votes. Then they weaken the legislature, change laws in their favour, and attack their political opponents through legal and ideological frameworks, portraying them as enemies to the nation's sovereignty. In other words, these regimes use democracy to undermine democracy.

The chief discussion of the book revolves around personalistic authoritarianism, a special variant of today's authoritarian regimes. In this form, the ideological framework posits the leader and their family as the supreme, above everything else in the nation, eventually creating a cult of personality. Another feature of personalistic authoritarianism is patrimonialism—the tendency to use state property as personal belongings. These behaviours include but aren't limited to nominating family members for the highest rank in different national organisations, acquitting them of criminal charges without proper investigation, and granting them property bypassing the law. The rule of order breaks down in this system, and the only way to ensure that a citizen can attain anything is their connection to the ruling authority. Processes become irrelevant, and institutions are made impotent.

Riaz reiterates the history of Bangladesh and its three authoritarian regimes, including the two non-military dictatorships in 1972-1975 and 2009-2024 and the military dictatorship of 1975-1990. He explains how Bangladesh can be a case study to test academic theories on authoritarianism. Issues with the formation of the constitution in 1972 are discussed, including how it put several restrictions on fundamental human rights such as freedom of speech. These articles were later used to legislate laws to crush dissent and opposition. In addition, the constitution put too much power in the hands of the prime minister and made them virtually above the law, which certainly eased the way into building a personalistic dictatorship—where one person's command is enough to overturn everything.

These were justified with an ideology which placed Sheikh Hasina and her family as the sole leaders of the Liberation War in 1971. Critics were silenced and anyone opposed to the regime was called 'anti-Liberation War', 'traitor', and 'threats to sovereignty'. The Sheikh family practically reigned over the country, which resembles the patrimonialism described by Riaz earlier. The Sheikh family and their members took decisions in the government bypassing existing laws and processes; here, Riaz gives an example of Adani's deal with Hasina, which was made solely by Sheikh Hasina despite continuous criticism from experts.

The final chapter discusses how to get out of such a situation. Riaz outlines a few solutions, such as strengthening the institutions which are to protect the democratic structure, such as the judiciary, human rights and anti-corruption agencies, the election commission, etc. He also suggests reforming the constitution to add checks and balances so that no one person has unmatched power—be it the president or the prime minister—and a change in political culture itself by ensuring democracy inside political parties and organisations first.

The July Uprising in 2024 has given Bangladesh new hope, and this time, citizens are demanding substantial change so that Bangladesh does not find itself face to face with another dictatorship. This book is a vital resource for achieving that goal, by analysing previous mistakes and formulating new pathways.

Sadman Ahmed Siam, as the name suggests, is indeed a sad man. Send him happy quotes at: siamahmed09944@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments